"Alamut is a historical fortress of the Nizari Ismailis. Its location in mountainous terrain lies about 100 km. Northwest of Tehran, and situated in the high peak of Elburz mountain. Alburz generally was pronounced as Elburz, is the name given to great mountain range, dividing the high plateau of Iran from the low lands of Caspian Sea. The original Iranian word Alburz is derived from two Zand words, signifying the high mountain. The fortress of Alamut is 600 feet high, 450 feet long and 30 to 125 feet wide and is partly encompassed by the towering Elburz range. The rock of Alamut is known at present as Qal'ai Guzur Khan.

The Justanid dynasty of Daylam was founded in 189/805, and one of its rulers, called Wahsudan bin Marzuban (d. 251/865) is reported to have built the fortress of Alamut in 246/860. Ibn Athir (d. 630/1234) records its anecdote in his Kamil fi't Tarikh (Beirut, 1975, 10:110) that once the ruler, while on hunting excursion had followed a manned eagle, which alighted on the rock. The king saw the strategic value of the location and built a fort on the top of a high piercing rock and was named aluh amut, which in the Daylami dialect, derived from aluh (eagle) and amut (nest), i.e., eagle's nest as the eagle, instead of following the birds, had built its nest on that location. According to Sar Guzasht-i Sayyidna, the term alamut is aluh amut i.e., the eagle's nest, and an eagle had its nest there. Ibn Athir relates another tradition that the eagle had taught and guided the king to this location, therefore, it was named talim al-aqab (the teaching or guidance of an eagle), whose rendering into Daylami dialect is aluh amut. The word aluh means eagle and amutis derived from amukhat means teaching. The people of Qazwin called it aqab amukhat (the teaching of eagle). Thus, the term aluh amut (or aqab amukhat) later on became known as Alamut. The Iranian historians have drawn attention that if one gives to each letter in the full name of Aluh Amut, its numerical value in the traditional abjad system of alpha-numeric corresponds the sum total of 483, which represents the year in which Hasan bin Sabbah obtained possession of Alamut, i.e. 483/1090.

Afterwards, the Musafirid dynasty, also known as Sallarids or Kangarids (304-483/916-1090) founded by Muhammad bin Musafir (304-330/916-941), who ruled from the fortress of Shamiran in the district of Tarum at Daylam and Azerbaijan. Later, Mahdi bin Khusaro Firuz, known as Siyahchashm, retained the occupation of Alamut. He was however defeated by the Musafirid ruler, Ibn Musafir in 316/928 and henceforward, there is no historical indication about the fate of Alamut following the death of Ibn Musafir in 319/931.

When Hasan bin Sabbah arrived in Iran from Egypt, the fortress of Alamut was in possession of an Alid, called Hussain Mahdi, who had it as a fief from the Seljuq sultan Malikshah. Hasan Mahdi was a descendant of Hasan bin Ali al-Utrush (d. 304/916), one of the Alid rulers of Tabaristan, also known as al-Nasir li'l-Haq, who had established a separate Zaidi community in the Caspian Sea. It is related that a da'i Hussain Qaini, working under Hasan bin Sabbah had created his friendship with Hussain Mahdi. The Ismaili da'is also converted a bulk of the people around the territory, and became powerful to some extent. These Ismailis also began to come in the fortress. Knowing this, Hussain Mahdi expelled them and closed its doors. Finally, Hussain Mahdi was compelled to open the doors due to the growing influence of the Ismailis in the vicinity.

Hasan bin Sabbah moved to Ashkawar and then Anjirud, adjacent to Alamut, and on Wednesday, the 6th Rajab, 483/September 4, 1090, he stealthily entered the castle of Alamut. He lodged there for a while in disguise, calling himself Dihkhuda and did not reveal his identity to Hussain Mahdi, but as the days rolled away, the latter noticed that he was no longer obeyed, that there was another master in Alamut. The bulk of Alamut's garrison and a large number of the inhabitants had embraced Ismailism, making Hussain Mahdi powerless to defend himself or make their expulsion, but himself left the fortress. Thus, Alamut was occupied without any massacre and taken to be known as daru'l hijra (place of refuge) for the Ismailis.

Ata Malik Juvaini (1226-1283) had seen the fortress of Alamut when it was being shattered in 654/1256. He writes in Tarikh-i Jhangusha (Cambridge, 1958, p. 719) that, "Alamut is a mountain which resembles a kneeling camel with its neck resting on the ground." It was situated in Daylam about 35 km. north-west of Qazwin in the region of Rudhbar. It was physically a large towering rock, with steep slopes hardly negotiable on most sides, but with a considerable expanse at its top where extensive building could be done.

Halagu, the Mongol commander reduced the fort of Alamut. He came with his forces at the foot of Alamut in 654/1256, whose Ismaili commander was Muqadinuddin. After a few days, the garrison of Alamut dismounted. Berthold Spuler writes in The Muslim World (London, 1969, 2:1

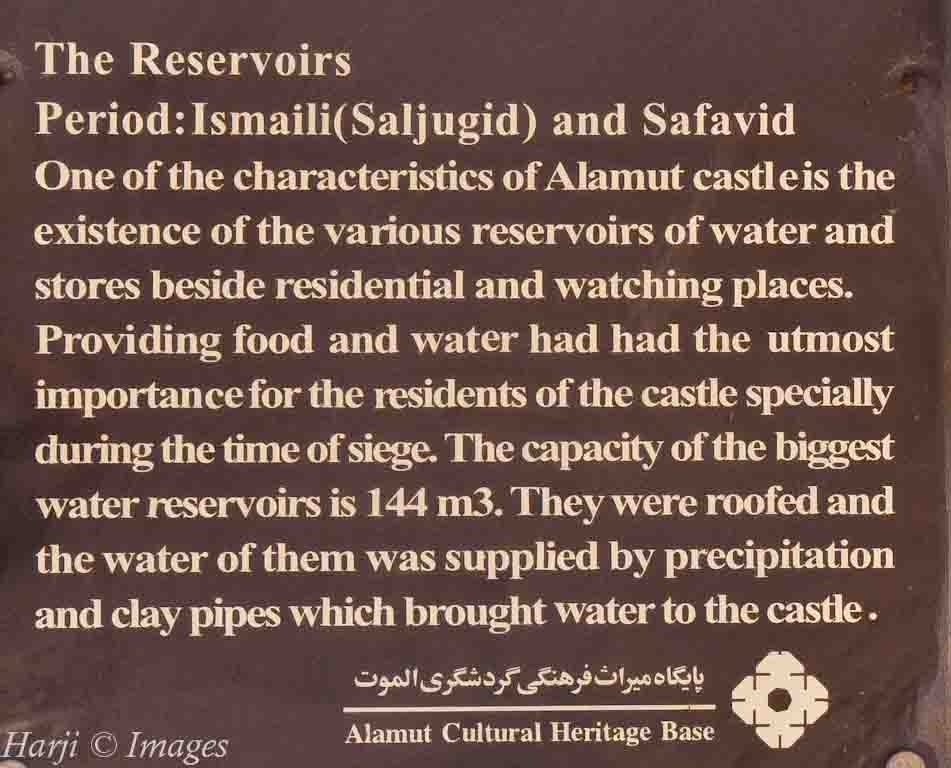

As for the Alamut, Juvaini writes, "It was a castle whereof the entries and exits, the ascents and approaches had been so strengthened by plastered walls and lead-covered ramparts that when it was being demolished, it was as though the iron struck its head on a stone, and it had nothing in its hand and yet resisted. And in the cavities of these rocks they had constructed several long, wide and tall galleries and deep tanks, dispensing with the use of stone and mortar...And from the river, they had brought a conduit to the foot of the castle and from thence a conduit was cut in the rock half way round the castle and ocean-like tanks, also of rock, constructed beneath so that the water would be stored in them by its own impetus and was continually flowing on. Most of these stores of liquids and solids, which they had been laying down from the time of Hasan-i Sabbah, that is over a period of more than 170 years, showed no sign of destruction, and this they regarded as a result of Hasan's sanctity. (2:720-1) Juvaini goes on to tell how a large body of Mongol soldiers were employed in demolishing the castle: "Picks were of no use: they set fire to the buildings and then broke them up, and this occupied them for a long time." (Ibid.)

The Ismaili rule in Alamut lasted for 171 years (483/1090-654/1256). In its early period, the following three hujjats were the rulers of the Alamut:-

1. Hasan bin Sabbah (483/1090-532/1138)

2. Kiya Buzrug Ummid (532/1138-532/1138)

3. Muhammad bin Kiya Buzrug (532/1138-554/1160)

The following eight Imams flourished during the Alamut rule:-

1. Imam Hadi bin Nizar (490-530/1097-1136)

2. Imam Mohtadi bin Hadi (530-552/1136-1157)

3. Imam Kahir (552-557/1157-1162)

4. Imam Hasan Ala Zikrihi's Salam (557-561/1162-1166)

5. Imam Ala Muhammad (561-607/1166-1210)

6 Imam Jalaluddin Hasan (607-618/1210-1221)

7. Imam Alauddin Muhammad (618-653/1221-1255)

8. Imam Ruknuddin Khurshah (653-655/1255-1257)

The Mongols in fact reconstructed Alamut and Lamasar and retained for their own use. When Halagu left Iran for his operations against Baghdad, the Ismaili commanders at remote distance had also surrendered their castles upon receipt of official orders without knowing veritable picture. Few among them are reported to have trekked in Rudhbar after the massacre of the Ismailis in 656/1257. They made an intensive search of the succeeding Imam after being known that Imam Ruknuddin Khurshah had been also killed. Hamidullah Mustawi (d. 750/1349) writes in Tarikh-i Guzida (1:583) that a group of the Ismailis led by the son of Imam Ruknuddin Khurshah, whose title was Naw Daulat or Abu Daulat, managed to obtain possession of Alamut in 674/1275. The reason for re-occupation, as we have been informed, was to give an inkling to the hiding Imam and the Ismailis to come out of concealment. If this version certainly embodies grain of truth, it implies that the Ismailis of Rudhbar were not yet acquainted with the whereabouts of the Imam. According to Tarikh-i Guzida (1:583), "They retained Alamut for almost one year before they were dislodged by a force sent against them by Halagu's son and successor Abaqa (d. 680/1282)."

Muhammad Shah (d. 807/1404), the son of Momin Shah bin Imam Shamsuddin Muhammad is reported to have appeared in Daylam. He is said to have joined Kiya Malik, the Hazaraspid ruler for taking the possession of Ashkawar. Muhammad Shah formed his force, and subdued Syed Mahdi Kiya with the help of Kiya Malik. Syed Mahdi Kiya was arrested and sent to Tabriz in the court of sultan Uways (757-776/1356-1374), the Jalayirid ruler of Azerbaijan. Kiya Malik reinstated his rule in Ashkawar, and granted the hold of Alamut and its locality to Muhammad Shah in 776/1374. Syed Mahdi Kiya released from imprisonment in 778/1376 with the influence of Tajuddin Amuli, the Zaidi Syed of Timjan. Soon afterwards, Syed Ali Kiya took field against Ashkawar and defeated Kiya Malik, who fled to Alamut in the hope of being assisted once again by Muhammad Shah, but failed, therefore, he took refuge with Taymur. Meanwhile, the forces of Syed Ali had laid siege to Alamut while pursuing Kiya Malik, and took possession of the stronghold. Syed Ali was later defeated and killed in 791/1389 by the Nasirwands of Lahijan. Kiya Malik returned to Daylam and captured Alamut from Amir Kiya'i Syeds. Soon afterwards, following the murder of Kiya Malik, Muhammad Shah appeared once again in Daylam, and took possession of Alamut. But he soon surrendered Alamut to the Gawbara ruler of Rustamdar, Malik Kayumarth bin Bisutun (d. 857/1453). Then, Alamut passed into the occupation of the rulers of Lahijan.

The Safavid Shah Suleman (d. 1105/1693) is reported to have used the fortress of Alamut as a state prison for the rebellious persons from among his courtiers and relatives. At that time, only a few Ismaili families resided in the lower Caspian region.

By: Dr. D.S. Merchant

Article Directory: http://www.articledashboard.com