Languages

Languages

11 Fascinating Facts About the Swahili Language

With an estimated 50 to 100 million Swahili speakers worldwide, it’s time to broaden the scope – there’s more to it than Hakuna Matata – and dive deeper into this relatively unknown East African language. Here are 11 interesting facts on Swahili.

It’s a rich mix of languages

Swahili is predominantly a mix of local Bantu languages and Arabic. Decades of intensive trade along the East African coast resulted in this mix of cultures. Besides Arabic and Bantu, Swahili also has English, Persian, Portuguese, German and French influences due to trade contact.

It has roots in Arabic

Around 35% of the Swahili vocabulary comes from Arabic, but Swahili has also quite literally adopted words from English, such as: polisi – police, televisheni – television, redio – radio, and baiskeli – bicycle.

It has millions of speakers

People whose mother tongue is Swahili, about five to 15 million worldwide, are often referred to as Waswahili.

It developed as a coastal trading language

The word for the Swahili language is Kiswahili. Sawahili is the plural for the Arabic word sahil, which means ‘coast’. Ki- at the beginning means coastal language. This is because Swahili arose as a trade language along the coastline, and is also best spoken along the coast. In 1928, the Zanzibar dialect called Kiunguja was chosen as the standard Swahili.

It is spoken in many countries

Swahili is the lingua franca (a common language adopted between two non-native speakers) of the East African Union and is the official language of Tanzania (official language), Kenya (official language next to English) and of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It is also widely spoken in Uganda and, in smaller numbers, in Burundi, Rwanda, North Zambia, Malawi and Mozambique.

It’s international in reach

Several international media outlets have various Swahili programmes, such as BBC Swahili.

It’s easy to learn

Thinking about learning an African language? Give Swahili a try. It’s the easiest African language for English speakers to learn, as it’s one of the few Sub-Saharan African languages without lexical tone, similar to English.

It developed as a coastal trading language

The word for the Swahili language is Kiswahili. Sawahili is the plural for the Arabic word sahil, which means ‘coast’. Ki- at the beginning means coastal language. This is because Swahili arose as a trade language along the coastline, and is also best spoken along the coast. In 1928, the Zanzibar dialect called Kiunguja was chosen as the standard Swahili.

It is spoken in many countries

Swahili is the lingua franca (a common language adopted between two non-native speakers) of the East African Union and is the official language of Tanzania (official language), Kenya (official language next to English) and of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It is also widely spoken in Uganda and, in smaller numbers, in Burundi, Rwanda, North Zambia, Malawi and Mozambique.

It’s international in reach

Several international media outlets have various Swahili programmes, such as BBC Swahili.

It’s easy to learn

Thinking about learning an African language? Give Swahili a try. It’s the easiest African language for English speakers to learn, as it’s one of the few Sub-Saharan African languages without lexical tone, similar to English.

It’s been around for centuries

The earliest known documents of the Swahili language are letters written in Arabic script, written in 1711 in the region of Kilwa, present-day Tanzania. They are now preserved in the Historical Archives of Goa, India.

https://theculturetrip.com/africa/kenya ... -language/

With an estimated 50 to 100 million Swahili speakers worldwide, it’s time to broaden the scope – there’s more to it than Hakuna Matata – and dive deeper into this relatively unknown East African language. Here are 11 interesting facts on Swahili.

It’s a rich mix of languages

Swahili is predominantly a mix of local Bantu languages and Arabic. Decades of intensive trade along the East African coast resulted in this mix of cultures. Besides Arabic and Bantu, Swahili also has English, Persian, Portuguese, German and French influences due to trade contact.

It has roots in Arabic

Around 35% of the Swahili vocabulary comes from Arabic, but Swahili has also quite literally adopted words from English, such as: polisi – police, televisheni – television, redio – radio, and baiskeli – bicycle.

It has millions of speakers

People whose mother tongue is Swahili, about five to 15 million worldwide, are often referred to as Waswahili.

It developed as a coastal trading language

The word for the Swahili language is Kiswahili. Sawahili is the plural for the Arabic word sahil, which means ‘coast’. Ki- at the beginning means coastal language. This is because Swahili arose as a trade language along the coastline, and is also best spoken along the coast. In 1928, the Zanzibar dialect called Kiunguja was chosen as the standard Swahili.

It is spoken in many countries

Swahili is the lingua franca (a common language adopted between two non-native speakers) of the East African Union and is the official language of Tanzania (official language), Kenya (official language next to English) and of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It is also widely spoken in Uganda and, in smaller numbers, in Burundi, Rwanda, North Zambia, Malawi and Mozambique.

It’s international in reach

Several international media outlets have various Swahili programmes, such as BBC Swahili.

It’s easy to learn

Thinking about learning an African language? Give Swahili a try. It’s the easiest African language for English speakers to learn, as it’s one of the few Sub-Saharan African languages without lexical tone, similar to English.

It developed as a coastal trading language

The word for the Swahili language is Kiswahili. Sawahili is the plural for the Arabic word sahil, which means ‘coast’. Ki- at the beginning means coastal language. This is because Swahili arose as a trade language along the coastline, and is also best spoken along the coast. In 1928, the Zanzibar dialect called Kiunguja was chosen as the standard Swahili.

It is spoken in many countries

Swahili is the lingua franca (a common language adopted between two non-native speakers) of the East African Union and is the official language of Tanzania (official language), Kenya (official language next to English) and of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It is also widely spoken in Uganda and, in smaller numbers, in Burundi, Rwanda, North Zambia, Malawi and Mozambique.

It’s international in reach

Several international media outlets have various Swahili programmes, such as BBC Swahili.

It’s easy to learn

Thinking about learning an African language? Give Swahili a try. It’s the easiest African language for English speakers to learn, as it’s one of the few Sub-Saharan African languages without lexical tone, similar to English.

It’s been around for centuries

The earliest known documents of the Swahili language are letters written in Arabic script, written in 1711 in the region of Kilwa, present-day Tanzania. They are now preserved in the Historical Archives of Goa, India.

https://theculturetrip.com/africa/kenya ... -language/

Making Arabic compulsory

Pervez Hoodbhoy Published February 13, 2021

The writer is an Islamabad-based physicist and writer.

IN every school of Islamabad every child shall henceforth be compelled to study the Arabic language from Grade 1 to Grade 5. Thereafter he or she shall learn Arabic grammar from Grade 6 to Grade 12. By unanimous vote, that’s what the Senate of Pakistan has decided. Introduced on Feb 1, 2021 as a private member’s bill by Senator Javed Abbasi of the PML-N, the Compulsory Teaching of Arabic Language Bill, 2020, will become an act of parliament once approved by the National Assembly. Thereafter it is likely to be applied across the country.

Should we citizens celebrate or be worried? That depends upon whether desired outcomes can be attained. Let’s therefore see what reasons were given by our lawmakers for the bill, one that will deeply impact many generations to come.

First, the bill states that proficiency in Arabic will “broaden the employment and business opportunities for the citizens of Pakistan” in rich Arab countries. While attraction to Arab oil wealth is understandable and has long been pursued, this reason is weak. Jobs and businesses go to persons with specific skills or those who have deliverables to offer.

Forcing students to learn Arabic won’t make them virtuous but setting good examples of moral behaviour might.

Just look at who gets invited to GCC countries. Westerners having zero familiarity with Arabic but high expertise are most sought after. Indians are a distant second, getting only about 10 per cent of high-level jobs with the rest performing menial and unskilled construction tasks. Pakistanis stand still further below with only 3pc at higher levels. This is because of low professional and life skills. With the Pakistani schoolchild now to be burdened with learning yet another language, achievement levels will further deteriorate.

If the Pakistani job seeker could use his school-learned Arabic to communicate with Arabs, would it improve matters? This is unlikely. Graduates from Pakistani madressahs seeking to understand the Holy Quran spend their lives trying to master classical Arabic. And yet they have zero job prospects in the Middle East. Present enrolment in Arabic language courses and university degree programmes is therefore very low. In fact, after starting such programmes over 20 to 30 years ago, some universities later closed them down.

For the boy now in an Islamabad school compelled to learn classical Arabic, communication with Arabs in their Arabic will not be easy. In fact, the poor fellow will be quite at sea. Only modern versions of Arabic are spoken in various Arab countries, not classical Arabic. Imagine that a Pakistani lad trained in ye olde Englisch — the “proper English” of Shakespeare or the Canterbury Tales — was to land up in today’s England. He might be a source of merriment but getting a job would be tough.

Second, the bill claims that school-taught Arabic will enable students to understand the Holy Quran better and so become better Muslims. Are the bill’s sponsors not aware that, beginning with Persian in the 10th century, the Quran has undergone translation into all major languages? This was necessary because it is extremely difficult for non-Arabs to understand the Quran’s wonderfully rich and nuanced classical Arabic.

Many scholars have spent entire lives performing such monumental translations, knowing that words have meanings that subtly change with time. But even so, no two translations completely agree and sometimes different interpretations emerge. Given these difficulties, absorbing the contents of the Quran through an Urdu translation is surely much easier for a Pakistani school student.

Deeply puzzling, therefore, is the statement from the minister of state for parliamentary affairs: “You cannot understand the message of Allah, if you do not know Arabic.” If true, that massively downgrades most Muslims living on this planet. The entire Muslim population of Indonesia, Malaysia, Bangladesh, Iran, or Turkey cannot be made to understand or speak Arabic. And what of those long dead Muslims who tried hard to follow the teachings of Islam but never learned — nor tried to learn — the Arabic language?

That knowing Arabic — any version — can make one a better person or create unity is a bizarre thought. If true, the Arab states would be standing together instead of several rushing to recognize Israel even as it gobbles up the last bits of Palestine. Has the Arabic language made Arab states beacons of moral integrity, parsimony, and high thinking? Are our senators claiming that today’s Arabs are paragons of virtue?

But truly, it would be wonderful if teaching Arabic to kids, and further jacking up the religious content of education, could change students for the better. Just imagine! Future Pakistani lawyers would not be rampaging goons who destroy court property and randomly attack patients in hospital emergency wards; our students would be reading books rather than noisily demonstrating for their “right to cheat”; our political leaders would not be looters and our generals would no longer have secret overseas business franchises.

While some chase such delusions, others nervously search for their civilizational roots in some faraway land — Saudi Arabia earlier and now Turkey. Thus quite a few are drawn to Arabic. But curiously, Arabs show no interest in reviving Arabic. Their new generations are hell-bent upon modernizing and moving towards English. Now for several decades, an energized Arab world has been luring American universities with large sums of money to open local campuses in GCC states.

Part of that investment is paying off. The success of Al-Amal, the UAE spacecraft that entered orbit around Mars some days ago, was officially celebrated as an Arab Muslim success. While one feels happy at this, it is really the triumph of Western technology harnessed by a few forward-looking Arabs who have learnt to speak the language of modern science. A thousand years ago that language was only Arabic. But in our epoch it is only English.

In forcing kids to learn Arabic, all those sitting in Pakistan’s Senate — with just a single exception — forgot that they are Pakistanis first and that Pakistan was made for Pakistanis. Rather than behave as snivelling cultural orphans seeking shelter in a rich uncle’s house, they need to take pride in the diversity and strength of the myriad local cultures and languages that make this land and its people.

The writer is an Islamabad-based physicist and writer.

Published in Dawn, February 13th, 2021

https://www.dawn.com/news/1607107/makin ... compulsory

Pervez Hoodbhoy Published February 13, 2021

The writer is an Islamabad-based physicist and writer.

IN every school of Islamabad every child shall henceforth be compelled to study the Arabic language from Grade 1 to Grade 5. Thereafter he or she shall learn Arabic grammar from Grade 6 to Grade 12. By unanimous vote, that’s what the Senate of Pakistan has decided. Introduced on Feb 1, 2021 as a private member’s bill by Senator Javed Abbasi of the PML-N, the Compulsory Teaching of Arabic Language Bill, 2020, will become an act of parliament once approved by the National Assembly. Thereafter it is likely to be applied across the country.

Should we citizens celebrate or be worried? That depends upon whether desired outcomes can be attained. Let’s therefore see what reasons were given by our lawmakers for the bill, one that will deeply impact many generations to come.

First, the bill states that proficiency in Arabic will “broaden the employment and business opportunities for the citizens of Pakistan” in rich Arab countries. While attraction to Arab oil wealth is understandable and has long been pursued, this reason is weak. Jobs and businesses go to persons with specific skills or those who have deliverables to offer.

Forcing students to learn Arabic won’t make them virtuous but setting good examples of moral behaviour might.

Just look at who gets invited to GCC countries. Westerners having zero familiarity with Arabic but high expertise are most sought after. Indians are a distant second, getting only about 10 per cent of high-level jobs with the rest performing menial and unskilled construction tasks. Pakistanis stand still further below with only 3pc at higher levels. This is because of low professional and life skills. With the Pakistani schoolchild now to be burdened with learning yet another language, achievement levels will further deteriorate.

If the Pakistani job seeker could use his school-learned Arabic to communicate with Arabs, would it improve matters? This is unlikely. Graduates from Pakistani madressahs seeking to understand the Holy Quran spend their lives trying to master classical Arabic. And yet they have zero job prospects in the Middle East. Present enrolment in Arabic language courses and university degree programmes is therefore very low. In fact, after starting such programmes over 20 to 30 years ago, some universities later closed them down.

For the boy now in an Islamabad school compelled to learn classical Arabic, communication with Arabs in their Arabic will not be easy. In fact, the poor fellow will be quite at sea. Only modern versions of Arabic are spoken in various Arab countries, not classical Arabic. Imagine that a Pakistani lad trained in ye olde Englisch — the “proper English” of Shakespeare or the Canterbury Tales — was to land up in today’s England. He might be a source of merriment but getting a job would be tough.

Second, the bill claims that school-taught Arabic will enable students to understand the Holy Quran better and so become better Muslims. Are the bill’s sponsors not aware that, beginning with Persian in the 10th century, the Quran has undergone translation into all major languages? This was necessary because it is extremely difficult for non-Arabs to understand the Quran’s wonderfully rich and nuanced classical Arabic.

Many scholars have spent entire lives performing such monumental translations, knowing that words have meanings that subtly change with time. But even so, no two translations completely agree and sometimes different interpretations emerge. Given these difficulties, absorbing the contents of the Quran through an Urdu translation is surely much easier for a Pakistani school student.

Deeply puzzling, therefore, is the statement from the minister of state for parliamentary affairs: “You cannot understand the message of Allah, if you do not know Arabic.” If true, that massively downgrades most Muslims living on this planet. The entire Muslim population of Indonesia, Malaysia, Bangladesh, Iran, or Turkey cannot be made to understand or speak Arabic. And what of those long dead Muslims who tried hard to follow the teachings of Islam but never learned — nor tried to learn — the Arabic language?

That knowing Arabic — any version — can make one a better person or create unity is a bizarre thought. If true, the Arab states would be standing together instead of several rushing to recognize Israel even as it gobbles up the last bits of Palestine. Has the Arabic language made Arab states beacons of moral integrity, parsimony, and high thinking? Are our senators claiming that today’s Arabs are paragons of virtue?

But truly, it would be wonderful if teaching Arabic to kids, and further jacking up the religious content of education, could change students for the better. Just imagine! Future Pakistani lawyers would not be rampaging goons who destroy court property and randomly attack patients in hospital emergency wards; our students would be reading books rather than noisily demonstrating for their “right to cheat”; our political leaders would not be looters and our generals would no longer have secret overseas business franchises.

While some chase such delusions, others nervously search for their civilizational roots in some faraway land — Saudi Arabia earlier and now Turkey. Thus quite a few are drawn to Arabic. But curiously, Arabs show no interest in reviving Arabic. Their new generations are hell-bent upon modernizing and moving towards English. Now for several decades, an energized Arab world has been luring American universities with large sums of money to open local campuses in GCC states.

Part of that investment is paying off. The success of Al-Amal, the UAE spacecraft that entered orbit around Mars some days ago, was officially celebrated as an Arab Muslim success. While one feels happy at this, it is really the triumph of Western technology harnessed by a few forward-looking Arabs who have learnt to speak the language of modern science. A thousand years ago that language was only Arabic. But in our epoch it is only English.

In forcing kids to learn Arabic, all those sitting in Pakistan’s Senate — with just a single exception — forgot that they are Pakistanis first and that Pakistan was made for Pakistanis. Rather than behave as snivelling cultural orphans seeking shelter in a rich uncle’s house, they need to take pride in the diversity and strength of the myriad local cultures and languages that make this land and its people.

The writer is an Islamabad-based physicist and writer.

Published in Dawn, February 13th, 2021

https://www.dawn.com/news/1607107/makin ... compulsory

It might be appropriate to reflect on MSMS's speech: ARABIC UNIVERSAL LANGUAGE OF MUSLIM WORLDswamidada wrote:Making Arabic compulsory

Pervez Hoodbhoy Published February 13, 2021

An address by the late H.H.Sir Sultan Mohammed Shah Aga Khan at a session of Motamer al-Alam-al-Islamiyya

http://ismaili.net/sultan/5msms.html

kmaherali wrote:It might be appropriate to reflect on MSMS's speech: ARABIC UNIVERSAL LANGUAGE OF MUSLIM WORLDswamidada wrote:Making Arabic compulsory

Pervez Hoodbhoy Published February 13, 2021

An address by the late H.H.Sir Sultan Mohammed Shah Aga Khan at a session of Motamer al-Alam-al-Islamiyya

http://ismaili.net/sultan/5msms.html

When Muhammad Ali Jinnah declared Urdu should be the national language of Pakistan protests erupted in the provinces of west Pakistan as well in east Pakistan ( now Bangla Desh). Bengalis rejected Urdu as their national language, they demanded Bangla as their national language. In 1948, at Dhaka university, when Jinnah declared Urdu as national language, university students lead by Mujeebur Rahman (at that time a student leader) confronted Jinnah and there were violent protests. That was the first dangerous step towards the creation of Bangla Desh in my opinion. The language issue created mistrust among Pakistanis, and to overcome this and for the unity of Pakistan Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah delivered that speech at Moutammar Alam e Islamiyah presented by Mata Salamat. Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah was requested by then Prime minister Liaquat Ali Khan not to attend that session due to disturbance. That speech irritated the Urdu speaking class and they criticized Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah including Baba e Urdu Moulvi Abdul Haqq. At that time Arabic was the best solution for the stability and unity of Pakistan. All other main languages should have been adopted second languages including Urdu beside Arabic as national language. The misstep of early leadership caused secession of east Pakistan.

Google translation of the original article in Portuguese: https://the.ismaili/portugal/import%C3% ... ngl%C3%AAs

The importance of learning English

In an increasingly connected world and, taking our global Jamat as an example, we are pressured to learn new languages so that we can participate in global events or develop relationships and friendships that cross borders. Don't hesitate, accept the challenge!

english

Without learning a global language like English, we can feel separate from the world in the most literal sense. So why - despite our innate desire and need to expand our linguistic horizons - are we so hesitant to take up the challenge?

It is common to hear adults, or even young people, say that they are simply too old to learn a new language and that it is simply too difficult. And many - despite not wanting to admit it - hesitate because they don't feel comfortable making mistakes in front of other people. But is learning a language, as we get older, that hard?

The truth is that everyone can - and should - learn a new language, regardless of their age. Learning never really ends and, in many ways, our motivation to expand our linguistic horizons only grows with age.

Mawlana Hazar Imam has been reiterating the importance of learning new languages and, above all, knowing how to speak and read English, so that we have the best access to global knowledge.

Learning a new language is always a challenge, whatever the person's age. But for a senior it becomes something attractive because, in addition to occupying time well, it exercises the mind.

Engaging in a new language has several advantages, including:

Exercise the mind;

Feeling useful;

Occupying the time and making new friends - meeting people with the same interests;

Being able to travel to different places, where the language you have learned is spoken, which allows you not to be dependent on excursions or family members, giving you a feeling of fullness;

Allows you to get more active and excited.

If you're still not completely convinced, check out the testimonies of some students in Basic English and Intermediate English classes, by clicking on the following videos:

Testimony 1 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6yBclevQEDg

Testimony 2 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zOkGB1qH4LU

Testimony 3 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0mA-eK46FRc

Testimony 4 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HPaHo7zLGFo

To access English classes, contact Elderly Care members:

Shelina Amad (Lisbon) - 968 385 002

Mehrunissa Bhanji (Seixal) - 933 146 764

The importance of learning English

In an increasingly connected world and, taking our global Jamat as an example, we are pressured to learn new languages so that we can participate in global events or develop relationships and friendships that cross borders. Don't hesitate, accept the challenge!

english

Without learning a global language like English, we can feel separate from the world in the most literal sense. So why - despite our innate desire and need to expand our linguistic horizons - are we so hesitant to take up the challenge?

It is common to hear adults, or even young people, say that they are simply too old to learn a new language and that it is simply too difficult. And many - despite not wanting to admit it - hesitate because they don't feel comfortable making mistakes in front of other people. But is learning a language, as we get older, that hard?

The truth is that everyone can - and should - learn a new language, regardless of their age. Learning never really ends and, in many ways, our motivation to expand our linguistic horizons only grows with age.

Mawlana Hazar Imam has been reiterating the importance of learning new languages and, above all, knowing how to speak and read English, so that we have the best access to global knowledge.

Learning a new language is always a challenge, whatever the person's age. But for a senior it becomes something attractive because, in addition to occupying time well, it exercises the mind.

Engaging in a new language has several advantages, including:

Exercise the mind;

Feeling useful;

Occupying the time and making new friends - meeting people with the same interests;

Being able to travel to different places, where the language you have learned is spoken, which allows you not to be dependent on excursions or family members, giving you a feeling of fullness;

Allows you to get more active and excited.

If you're still not completely convinced, check out the testimonies of some students in Basic English and Intermediate English classes, by clicking on the following videos:

Testimony 1 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6yBclevQEDg

Testimony 2 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zOkGB1qH4LU

Testimony 3 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0mA-eK46FRc

Testimony 4 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HPaHo7zLGFo

To access English classes, contact Elderly Care members:

Shelina Amad (Lisbon) - 968 385 002

Mehrunissa Bhanji (Seixal) - 933 146 764

Google translation of the original article in Portuguese: https://the.ismaili/portugal/english4al ... m-connosco

English4All - Embark on this trip with us

Are you between 12 and 16 years old and would like to be fluent in the English language? Then this program is for you!

The Aga Khan Education Board (AKEB), in partnership with the Butterflies Learning Center, is launching the English4All program - English classes, taught at Cambridge, for young students aged between 12 and 16 years old. We will provide three levels of education:

- Young Learners - Starters, Movers and Flyers - introductory level to English - speaking, writing and everyday communication.

- Preliminary level (PET) - to develop fundamental language skills - general culture.

- First Certificate Level (FCE) - development of effective communication on various topics, with an emphasis on writing and analytical skills.

When?

From September 2021 to June 2022 - with the possibility of taking the Cambridge Exam at the end of the school year.

At where?

At the Ismaili Center, Lisbon*

Like?

You will take a scouting test at the beginning of September and then you will be integrated into the class that corresponds to your level of knowledge.

Tuition

English4All is the result of a partnership with the Butterflies Learning Centre, which allows these English classes to be made available at more affordable prices than those found in the market:

- Young Learners - Starters, Movers and Flyers: 47€/month/student

Preliminary Level (PET): 86€/month/student

- First Certificate Level (FCE): €140/month/student

- At the same time, you can also have access to a scholarship funded up to 50% by the Aga Khan Education Board (subject to the assessment of each student's financial situation and merit).

We want to help you develop functional English in an accessible way and also so that you can achieve a high degree of excellence both academically and professionally, as well as on a personal level.

Ready to sign up? Fill out this form with your parents: https://bit.ly/Formul árioEnglish4All

For more information, we are available at: [email protected](link sends email)

*If the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic does not allow, these classes will be held online.

English4All - Embark on this trip with us

Are you between 12 and 16 years old and would like to be fluent in the English language? Then this program is for you!

The Aga Khan Education Board (AKEB), in partnership with the Butterflies Learning Center, is launching the English4All program - English classes, taught at Cambridge, for young students aged between 12 and 16 years old. We will provide three levels of education:

- Young Learners - Starters, Movers and Flyers - introductory level to English - speaking, writing and everyday communication.

- Preliminary level (PET) - to develop fundamental language skills - general culture.

- First Certificate Level (FCE) - development of effective communication on various topics, with an emphasis on writing and analytical skills.

When?

From September 2021 to June 2022 - with the possibility of taking the Cambridge Exam at the end of the school year.

At where?

At the Ismaili Center, Lisbon*

Like?

You will take a scouting test at the beginning of September and then you will be integrated into the class that corresponds to your level of knowledge.

Tuition

English4All is the result of a partnership with the Butterflies Learning Centre, which allows these English classes to be made available at more affordable prices than those found in the market:

- Young Learners - Starters, Movers and Flyers: 47€/month/student

Preliminary Level (PET): 86€/month/student

- First Certificate Level (FCE): €140/month/student

- At the same time, you can also have access to a scholarship funded up to 50% by the Aga Khan Education Board (subject to the assessment of each student's financial situation and merit).

We want to help you develop functional English in an accessible way and also so that you can achieve a high degree of excellence both academically and professionally, as well as on a personal level.

Ready to sign up? Fill out this form with your parents: https://bit.ly/Formul árioEnglish4All

For more information, we are available at: [email protected](link sends email)

*If the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic does not allow, these classes will be held online.

Tut, a Language Used by Enslaved Africans, Is Resurfacing on Social Media

Rachel Pilgrim

Tue, August 17, 2021, 2:00 PM

For many of us who grew up reading I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou for our 9th grade English class, we remember Angelou trying to learn Tut, a complicated language used by enslaved Africans, with her friend Louise while the other kids were learning Pig Latin.

However, Tut has been the latest to enter the why-didn’t-we-learn-about-this-in-history-class forum as Black Americans have been rediscovering the lost dialect used amongst our enslaved ancestors.

According to NBC News, Tut was used in the 18th century to communicate covertly in front of slave masters. The words sound distinctively English, but require each letter of the English alphabet to have its own unique sound. For example, according to author Gloria McIlwain in the American Speech Journal, the letter i becomes “ay” and the letter h becomes “hash.” She says it’s how enslaved people in the South taught one another to read and write during a time when literacy was illegal.

African Americans are learning Tut and sharing videos, guides, and notes for speaking the language across different platforms, but some want to keep the language under wraps. Social media pages dedicated to teaching Tutnese have surfaced asking for the learning space to be exclusive to descendants of slavery, and the fear that Black people will have another cultural or social identifier coopted is a justified fear.

Tut isn’t the only language that Black Americans in the U.S. speak. Creole, in Louisiana, and Gullah, in South Carolina, are languages that have been culturally preserved amongst descendants of enslaved Africans and are still spoken today.

It is unsurprising that Tut or Tutnese was lost over the centuries; it’s unfortunately the fate that many contact languages meet over time. In a story for BBC, Nala H. Lee, a linguist at the National University of Singapore, says that when people judge contact languages, “People think of them as being less good or not real languages.” But in the last few months, Black Americans are ready to reclaim the voices of their ancestors one syllable at a time.

https://currently.att.yahoo.com/lifesty ... 00776.html

Rachel Pilgrim

Tue, August 17, 2021, 2:00 PM

For many of us who grew up reading I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou for our 9th grade English class, we remember Angelou trying to learn Tut, a complicated language used by enslaved Africans, with her friend Louise while the other kids were learning Pig Latin.

However, Tut has been the latest to enter the why-didn’t-we-learn-about-this-in-history-class forum as Black Americans have been rediscovering the lost dialect used amongst our enslaved ancestors.

According to NBC News, Tut was used in the 18th century to communicate covertly in front of slave masters. The words sound distinctively English, but require each letter of the English alphabet to have its own unique sound. For example, according to author Gloria McIlwain in the American Speech Journal, the letter i becomes “ay” and the letter h becomes “hash.” She says it’s how enslaved people in the South taught one another to read and write during a time when literacy was illegal.

African Americans are learning Tut and sharing videos, guides, and notes for speaking the language across different platforms, but some want to keep the language under wraps. Social media pages dedicated to teaching Tutnese have surfaced asking for the learning space to be exclusive to descendants of slavery, and the fear that Black people will have another cultural or social identifier coopted is a justified fear.

Tut isn’t the only language that Black Americans in the U.S. speak. Creole, in Louisiana, and Gullah, in South Carolina, are languages that have been culturally preserved amongst descendants of enslaved Africans and are still spoken today.

It is unsurprising that Tut or Tutnese was lost over the centuries; it’s unfortunately the fate that many contact languages meet over time. In a story for BBC, Nala H. Lee, a linguist at the National University of Singapore, says that when people judge contact languages, “People think of them as being less good or not real languages.” But in the last few months, Black Americans are ready to reclaim the voices of their ancestors one syllable at a time.

https://currently.att.yahoo.com/lifesty ... 00776.html

The Unusual Language That Linguists Thought Couldn’t Exist

In most languages, sounds can be re-arranged into any number of combinations. Not so in Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language.

Languages, like human bodies, come in a variety of shapes—but only to a point. Just as people don’t sprout multiple heads, languages tend to veer away from certain forms that might spring from an imaginative mind. For example, one core property of human languages is known as duality of patterning: meaningful linguistic units (such as words) break down into smaller meaningless units (sounds), so that the words sap, pass, and asp involve different combinations of the same sounds, even though their meanings are completely unrelated.

It’s not hard to imagine that things could have been otherwise. In principle, we could have a language in which sounds relate holistically to their meanings—a high-pitched yowl might mean “finger,” a guttural purr might mean “dark,” a yodel might mean “broccoli,” and so on. But there are stark advantages to duality of patterning. Try inventing a lexicon of tens of thousands of distinct noises, all of which are easily distinguished, and you will probably find yourself wishing you could simply re-use a few snippets of sound in varying arrangements.

The sign for “lemon” resembles the motion of squeezing a lemon.

As Elizabeth Svoboda notes in her Nautilus article, “The Family That Couldn’t Say Hippopotamus,” the dominant thinking until fairly recently was that universal linguistic properties reflect genetic predispositions. Under this view, duality of patterning is much like an opposable thumb: It evolved within our species because it was advantageous, and now exists as part of our genetic heritage. We are born expecting language to have duality of patterning.

What to make, then, of the recent discovery of a language whose words are not made from smaller, meaningless units? Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language (ABSL) is a new sign language emerging in a village with high rates of inherited deafness in Israel’s Negev Desert. According to a report led by Wendy Sandler of the University of Haifa, words in this language correspond to holistic gestures, much like the imaginary sound-based language described above, even though ABSL has a sizable vocabulary.

To linguists, this is akin to finding a planet on which matter is made up of molecules that don’t decompose into atoms. ABSL contrasts sharply with other sign languages like American Sign Language (ASL), which creates words by re-combining a small collection of gestural elements such as hand shapes, movements, and hand positions.

The documentary Voices From El-Sayed considered what would happen to the village when children living there started receiving cochlear implants.

ABSL provides fodder for researchers who reject the idea that there’s a genetic basis for the similarities found across languages. Instead, they argue, languages share certain properties because they all have to solve similar problems of communication under similar pressures, pressures that reflect the limits of human abilities to learn, remember, produce, and perceive information. The challenge, then, is to explain why ABSL is an outlier—if duality of patterning is the optimal solution to the problem of creating a large but manageable collection of words, why hasn’t ABSL made use of it?

One possible explanation is that the vocabulary of ABSL hasn’t yet reached a critical mass that would force it into a more combinatorial system for word-creation. This doesn’t look like the full story though. In a study by Tessa Verhoef of the University of Amsterdam, people tried to reproduce a mere 12 sounds of a “language” produced on a slide whistle. Each person’s attempts to replicate the language served as the new version of the language to be learned by the next subject, so that each new learner represented a “generation” in the life of the language. Over just 10 “generations,” learners began to change the original sounds to involve combined sequences of smaller sound patterns. The later iterations of the language were easier to learn than the original holistic sounds, suggesting there’s a learning advantage to breaking down even a very small number of complex sounds into smaller ingredients. In some cases, at least, duality of patterning kicks in at a surprisingly small number of “words.”

The signs of ABSL, though, may be easier to learn because many of them are concretely related to the things they symbolize—for example, the sign for “lemon” resembles the motion of squeezing a lemon. Another lab study led by Gareth Roberts of Yeshiva University found that both large vocabularies and abstract (as opposed to concrete) symbols encouraged the birth of duality of patterning in artificial languages. Concreteness may be easier to achieve in a gestural language than an auditory one, simply because you can illustrate more ideas using your hands than by making sounds with your mouth.

Researchers don’t yet have a clear answer for why ABSL looks as it does, but systematic lab studies may help solve this puzzle, as may the evolution of ABSL itself; Sandler and her colleagues see hints that ABSL is on the cusp of evolving a more combinatorial system. This intriguing language and the research it inspires may eventually tell us something profound about how languages emerge from the human mind, and why so many of them share some important similarities.

Julie Sedivy has taught linguistics and psychology at Brown University and the University of Calgary, and is the author of Language in Mind: An Introduction to Psycholinguistics. She is currently writing a book about losing and reclaiming a native tongue.

Watch documentary at:

https://nautil.us/blog/-the-unusual-lan ... ldnt-exist

In most languages, sounds can be re-arranged into any number of combinations. Not so in Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language.

Languages, like human bodies, come in a variety of shapes—but only to a point. Just as people don’t sprout multiple heads, languages tend to veer away from certain forms that might spring from an imaginative mind. For example, one core property of human languages is known as duality of patterning: meaningful linguistic units (such as words) break down into smaller meaningless units (sounds), so that the words sap, pass, and asp involve different combinations of the same sounds, even though their meanings are completely unrelated.

It’s not hard to imagine that things could have been otherwise. In principle, we could have a language in which sounds relate holistically to their meanings—a high-pitched yowl might mean “finger,” a guttural purr might mean “dark,” a yodel might mean “broccoli,” and so on. But there are stark advantages to duality of patterning. Try inventing a lexicon of tens of thousands of distinct noises, all of which are easily distinguished, and you will probably find yourself wishing you could simply re-use a few snippets of sound in varying arrangements.

The sign for “lemon” resembles the motion of squeezing a lemon.

As Elizabeth Svoboda notes in her Nautilus article, “The Family That Couldn’t Say Hippopotamus,” the dominant thinking until fairly recently was that universal linguistic properties reflect genetic predispositions. Under this view, duality of patterning is much like an opposable thumb: It evolved within our species because it was advantageous, and now exists as part of our genetic heritage. We are born expecting language to have duality of patterning.

What to make, then, of the recent discovery of a language whose words are not made from smaller, meaningless units? Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language (ABSL) is a new sign language emerging in a village with high rates of inherited deafness in Israel’s Negev Desert. According to a report led by Wendy Sandler of the University of Haifa, words in this language correspond to holistic gestures, much like the imaginary sound-based language described above, even though ABSL has a sizable vocabulary.

To linguists, this is akin to finding a planet on which matter is made up of molecules that don’t decompose into atoms. ABSL contrasts sharply with other sign languages like American Sign Language (ASL), which creates words by re-combining a small collection of gestural elements such as hand shapes, movements, and hand positions.

The documentary Voices From El-Sayed considered what would happen to the village when children living there started receiving cochlear implants.

ABSL provides fodder for researchers who reject the idea that there’s a genetic basis for the similarities found across languages. Instead, they argue, languages share certain properties because they all have to solve similar problems of communication under similar pressures, pressures that reflect the limits of human abilities to learn, remember, produce, and perceive information. The challenge, then, is to explain why ABSL is an outlier—if duality of patterning is the optimal solution to the problem of creating a large but manageable collection of words, why hasn’t ABSL made use of it?

One possible explanation is that the vocabulary of ABSL hasn’t yet reached a critical mass that would force it into a more combinatorial system for word-creation. This doesn’t look like the full story though. In a study by Tessa Verhoef of the University of Amsterdam, people tried to reproduce a mere 12 sounds of a “language” produced on a slide whistle. Each person’s attempts to replicate the language served as the new version of the language to be learned by the next subject, so that each new learner represented a “generation” in the life of the language. Over just 10 “generations,” learners began to change the original sounds to involve combined sequences of smaller sound patterns. The later iterations of the language were easier to learn than the original holistic sounds, suggesting there’s a learning advantage to breaking down even a very small number of complex sounds into smaller ingredients. In some cases, at least, duality of patterning kicks in at a surprisingly small number of “words.”

The signs of ABSL, though, may be easier to learn because many of them are concretely related to the things they symbolize—for example, the sign for “lemon” resembles the motion of squeezing a lemon. Another lab study led by Gareth Roberts of Yeshiva University found that both large vocabularies and abstract (as opposed to concrete) symbols encouraged the birth of duality of patterning in artificial languages. Concreteness may be easier to achieve in a gestural language than an auditory one, simply because you can illustrate more ideas using your hands than by making sounds with your mouth.

Researchers don’t yet have a clear answer for why ABSL looks as it does, but systematic lab studies may help solve this puzzle, as may the evolution of ABSL itself; Sandler and her colleagues see hints that ABSL is on the cusp of evolving a more combinatorial system. This intriguing language and the research it inspires may eventually tell us something profound about how languages emerge from the human mind, and why so many of them share some important similarities.

Julie Sedivy has taught linguistics and psychology at Brown University and the University of Calgary, and is the author of Language in Mind: An Introduction to Psycholinguistics. She is currently writing a book about losing and reclaiming a native tongue.

Watch documentary at:

https://nautil.us/blog/-the-unusual-lan ... ldnt-exist

Language Is the Scaffold of the Mind

Once we acquire language, we can live without it.

Can you imagine a mind without language? More specifically, can you imagine your mind without language? Can you think, plan, or relate to other people if you lack words to help structure your experiences?

Many great thinkers have drawn a strong connection between language and the mind. Oscar Wilde called language “the parent, and not the child, of thought”; Ludwig Wittgenstein claimed that “the limits of my language mean the limits of my world”; and Bertrand Russell stated that the role of language is “to make possible thoughts which could not exist without it.”

After all, language is what makes us human, what lies at the root of our awareness, our intellect, our sense of self. Without it, we cannot plan, cannot communicate, cannot think. Or can we?

Imagine growing up without words. You live in a typical industrialized household, but you are somehow unable to learn the language of your parents. That means that you do not have access to education; you cannot properly communicate with your family other than through a set of idiosyncratic gestures; you never get properly exposed to abstract ideas such as “justice” or “global warming.” All you know comes from direct experience with the world.

It might seem that this scenario is purely hypothetical. There aren’t any cases of language deprivation in modern industrialized societies, right? It turns out there are. Many deaf children born into hearing families face exactly this issue. They cannot hear and, as a result, do not have access to their linguistic environment. Unless the parents learn sign language, the child’s language access will be delayed and, in some cases, missing completely.

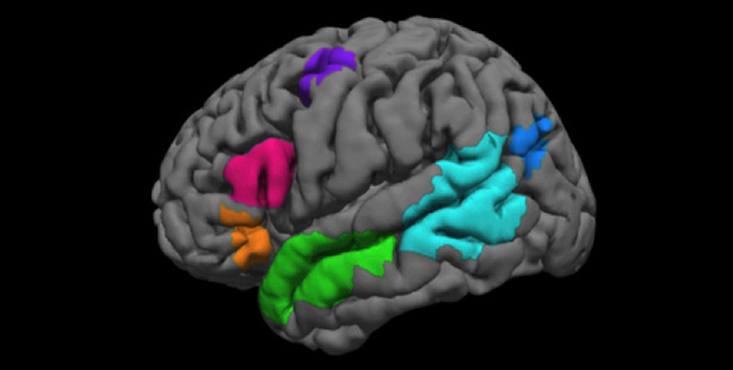

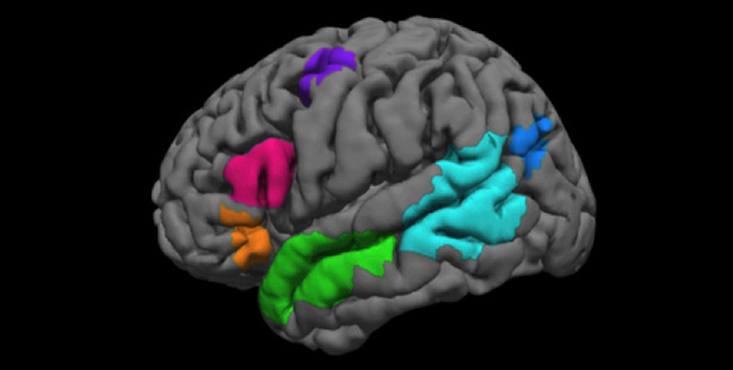

INNER VOICES: A set of brain regions within the left hemisphere, shown in color, responds strongly and selectively to language, but not to other thought-related processes.

Does our mind develop normally under such circumstances? Of course not. Language enables us to receive vast amounts of information we would have never acquired otherwise. The details of your parents’ wedding. The Declaration of Independence. The entrée section of the dinner menu. The entire richness of human experience condensed into a linear sequence of words. Take language away, and the amount of information you can acquire decreases dramatically.

The lack of language affects even functions that do not seem to be intrinsically “linguistic,” such as math. Developmental research shows that keeping track of exact numbers above four requires knowing the words for these numbers. Imagine trying to tell the difference between seven apples and eight apples. The task becomes almost impossible if you can’t count them—and you can’t count them if you never learn that “seven” is followed by “eight.” As a result of this language-number interdependency, many deaf children in industrialized societies fall behind in math, precisely because they did not learn to count early on.1

Without language, we cannot plan, cannot communicate, cannot think. Or can we?

Another part of your mind that needs language to develop properly is social cognition. Think about your interactions with your family and friends. Why is your mom upset? Why did your friend go inside the house just now? Understanding social situations requires inferring what the people around you are thinking.

This ability to infer another person’s thoughts is known as “theory of mind”; typically developing kids acquire this skill by age 5 or so. However, children with delayed language access have trouble imagining the mental state of other people.2 Moreover, brain regions involved in inferring others’ thoughts work differently in such children: They are active during all kinds of social situations, unable to properly distinguish scenarios that require mentalizing from those that do not.3 Theory of mind, therefore, is a prime example of a non-linguistic process that suffers if linguistic input is delayed.

So far, the evidence we have seen does suggest that “the limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” However, what happens if language disappears once the mind is fully developed? Will we then lose the ability to use math and understand others?

Imagine you are a typical adult; let’s say you’re 40. You wake up one day, and suddenly, you realize that your language is gone. You look around the room, but no words come to mind to describe the objects you see. You’re starting to plan out your day, but no half-formed phrases rush through your mind. You unlock your smartphone, but, instead of text, you see a sea of squiggles. Desperate, you cry out for help, and someone rushes up to you—but, instead of speech, all you hear is meaningless murmur.

The condition I have just described is known as global aphasia. It arises from severe damage to the brain, often as a result of a massive stroke. While some aphasias are temporary, in some cases the damage is irreparable, and the person may lose language for life. In your case, let’s say that a dozen doctors examined you and said (or, you think they said) that nothing can be done. If the limits of your language mean the limits of your world, should you conclude the way you experience the world is now fundamentally limited? Do you even have a mind?

Desperate, you attempt to figure out what cognitive functions you still have left. Can you count? 1, 2, 3 … You take a pen and write 5+7=12. You get a little bolder and attempt to multiply 12 by 5 in your mind, then 12 by 51 on paper. It works! Turns out, losing language as an adult does not prevent you from using math.

You meet up with some friends. You cannot understand a word they say, but you try to gesticulate—at least it’s an attempt at a conversation. You notice that they exchange guilty looks, then start discussing something in hushed voices (no need, since you don’t know what they’re saying anyway). You realize that they each thought the other one was going to bring a gift. You chuckle. Even though you can’t really communicate with your friends anymore, you still know what’s on their mind.

My experience of the world is not made less by lack of language but is essentially unchanged.

Research on adult individuals with aphasia has demonstrated that math, theory of mind, and many other cognitive abilities are independent from language.4 Patients with severe language impairments perform comparably to the rest of us when asked to complete arithmetic tasks, reason about people’s intentions, determine physical causes of actions, or decide whether a drawing depicts a real-life event. Some of them play chess in their spare time. Some even engage in creative tasks. Soviet composer Vissarion Shebalin continued to write music even after a stroke that left him severely aphasic.

Neuroimaging evidence also supports the claim that language in adults is separate from the rest of cognition. In recent years, neuroscientists have isolated a network of brain regions (typically in the left hemisphere) that react almost exclusively to linguistic input.5 They respond to written sentences, spoken narratives, words, monologues, conversations, but will not activate in response to memory tasks, spatial reasoning, music, math, or social situations that do not involve dialogue. No wonder many patients with aphasia do not have impairments in other cognitive domains—language and other functions are housed in separate chunks of brain matter.

Ihave to admit, not all writers support Wittgenstein’s and Russell’s idea that language and thought are inseparable. Tom Lubbock, a British writer and illustrator whose language system gradually deteriorated because of a brain tumor, wrote in his memoir shortly before his death in 2011:

My language to describe things in the world is very small, limited. My thoughts when I look at the world are vast, limitless and normal, same as they ever were. My experience of the world is not made less by lack of language but is essentially unchanged.

So, what can we say about the role language plays in shaping our minds? Well, pick a mind that is still developing, and you will find that removing language will alter it for life. However, pick a mind that is fully formed and take all words away, and you will discover that the rest of cognition remains mostly intact. Our language is but a scaffold for our minds: indispensable during construction but not necessary for the building to remain in place.

Anna Ivanova is a Ph.D. student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She studies the neural basis of language and semantics under the wise guidance of Ev Fedorenko and Nancy Kanwisher. You can find her on Twitter as @neuranna.

https://nautil.us/issue/76/language/lan ... f-the-mind

Once we acquire language, we can live without it.

Can you imagine a mind without language? More specifically, can you imagine your mind without language? Can you think, plan, or relate to other people if you lack words to help structure your experiences?

Many great thinkers have drawn a strong connection between language and the mind. Oscar Wilde called language “the parent, and not the child, of thought”; Ludwig Wittgenstein claimed that “the limits of my language mean the limits of my world”; and Bertrand Russell stated that the role of language is “to make possible thoughts which could not exist without it.”

After all, language is what makes us human, what lies at the root of our awareness, our intellect, our sense of self. Without it, we cannot plan, cannot communicate, cannot think. Or can we?

Imagine growing up without words. You live in a typical industrialized household, but you are somehow unable to learn the language of your parents. That means that you do not have access to education; you cannot properly communicate with your family other than through a set of idiosyncratic gestures; you never get properly exposed to abstract ideas such as “justice” or “global warming.” All you know comes from direct experience with the world.

It might seem that this scenario is purely hypothetical. There aren’t any cases of language deprivation in modern industrialized societies, right? It turns out there are. Many deaf children born into hearing families face exactly this issue. They cannot hear and, as a result, do not have access to their linguistic environment. Unless the parents learn sign language, the child’s language access will be delayed and, in some cases, missing completely.

INNER VOICES: A set of brain regions within the left hemisphere, shown in color, responds strongly and selectively to language, but not to other thought-related processes.

Does our mind develop normally under such circumstances? Of course not. Language enables us to receive vast amounts of information we would have never acquired otherwise. The details of your parents’ wedding. The Declaration of Independence. The entrée section of the dinner menu. The entire richness of human experience condensed into a linear sequence of words. Take language away, and the amount of information you can acquire decreases dramatically.

The lack of language affects even functions that do not seem to be intrinsically “linguistic,” such as math. Developmental research shows that keeping track of exact numbers above four requires knowing the words for these numbers. Imagine trying to tell the difference between seven apples and eight apples. The task becomes almost impossible if you can’t count them—and you can’t count them if you never learn that “seven” is followed by “eight.” As a result of this language-number interdependency, many deaf children in industrialized societies fall behind in math, precisely because they did not learn to count early on.1

Without language, we cannot plan, cannot communicate, cannot think. Or can we?

Another part of your mind that needs language to develop properly is social cognition. Think about your interactions with your family and friends. Why is your mom upset? Why did your friend go inside the house just now? Understanding social situations requires inferring what the people around you are thinking.

This ability to infer another person’s thoughts is known as “theory of mind”; typically developing kids acquire this skill by age 5 or so. However, children with delayed language access have trouble imagining the mental state of other people.2 Moreover, brain regions involved in inferring others’ thoughts work differently in such children: They are active during all kinds of social situations, unable to properly distinguish scenarios that require mentalizing from those that do not.3 Theory of mind, therefore, is a prime example of a non-linguistic process that suffers if linguistic input is delayed.

So far, the evidence we have seen does suggest that “the limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” However, what happens if language disappears once the mind is fully developed? Will we then lose the ability to use math and understand others?

Imagine you are a typical adult; let’s say you’re 40. You wake up one day, and suddenly, you realize that your language is gone. You look around the room, but no words come to mind to describe the objects you see. You’re starting to plan out your day, but no half-formed phrases rush through your mind. You unlock your smartphone, but, instead of text, you see a sea of squiggles. Desperate, you cry out for help, and someone rushes up to you—but, instead of speech, all you hear is meaningless murmur.

The condition I have just described is known as global aphasia. It arises from severe damage to the brain, often as a result of a massive stroke. While some aphasias are temporary, in some cases the damage is irreparable, and the person may lose language for life. In your case, let’s say that a dozen doctors examined you and said (or, you think they said) that nothing can be done. If the limits of your language mean the limits of your world, should you conclude the way you experience the world is now fundamentally limited? Do you even have a mind?

Desperate, you attempt to figure out what cognitive functions you still have left. Can you count? 1, 2, 3 … You take a pen and write 5+7=12. You get a little bolder and attempt to multiply 12 by 5 in your mind, then 12 by 51 on paper. It works! Turns out, losing language as an adult does not prevent you from using math.

You meet up with some friends. You cannot understand a word they say, but you try to gesticulate—at least it’s an attempt at a conversation. You notice that they exchange guilty looks, then start discussing something in hushed voices (no need, since you don’t know what they’re saying anyway). You realize that they each thought the other one was going to bring a gift. You chuckle. Even though you can’t really communicate with your friends anymore, you still know what’s on their mind.

My experience of the world is not made less by lack of language but is essentially unchanged.

Research on adult individuals with aphasia has demonstrated that math, theory of mind, and many other cognitive abilities are independent from language.4 Patients with severe language impairments perform comparably to the rest of us when asked to complete arithmetic tasks, reason about people’s intentions, determine physical causes of actions, or decide whether a drawing depicts a real-life event. Some of them play chess in their spare time. Some even engage in creative tasks. Soviet composer Vissarion Shebalin continued to write music even after a stroke that left him severely aphasic.

Neuroimaging evidence also supports the claim that language in adults is separate from the rest of cognition. In recent years, neuroscientists have isolated a network of brain regions (typically in the left hemisphere) that react almost exclusively to linguistic input.5 They respond to written sentences, spoken narratives, words, monologues, conversations, but will not activate in response to memory tasks, spatial reasoning, music, math, or social situations that do not involve dialogue. No wonder many patients with aphasia do not have impairments in other cognitive domains—language and other functions are housed in separate chunks of brain matter.

Ihave to admit, not all writers support Wittgenstein’s and Russell’s idea that language and thought are inseparable. Tom Lubbock, a British writer and illustrator whose language system gradually deteriorated because of a brain tumor, wrote in his memoir shortly before his death in 2011:

My language to describe things in the world is very small, limited. My thoughts when I look at the world are vast, limitless and normal, same as they ever were. My experience of the world is not made less by lack of language but is essentially unchanged.

So, what can we say about the role language plays in shaping our minds? Well, pick a mind that is still developing, and you will find that removing language will alter it for life. However, pick a mind that is fully formed and take all words away, and you will discover that the rest of cognition remains mostly intact. Our language is but a scaffold for our minds: indispensable during construction but not necessary for the building to remain in place.

Anna Ivanova is a Ph.D. student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She studies the neural basis of language and semantics under the wise guidance of Ev Fedorenko and Nancy Kanwisher. You can find her on Twitter as @neuranna.

https://nautil.us/issue/76/language/lan ... f-the-mind

United Nations Declares 7 July As World Kiswahili Day

Video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=nOohAUmyb7g

The United Nations has declared 7 July each year as the world’s official day to celebrate the Swahili language. It is the first African language to be recognised by the UN and have its own day of celebration. Swahili is also the only African language to have been officially recognised by the African Union. Swahili, also known by its native name Kiswahili, is a Bantu language and the native language of the Swahili people.The exact number of Swahili speakers, be they native or second-language speakers, is estimated to be between 100 million to 200 million.

In 2018, South Africa legalised the teaching of Swahili in schools as an optional subject to begin in 2020. Botswana followed in 2020, and Namibia plans to introduce the language as well. Shikomor (or Comorian), an official language in Comoros and also spoken in Mayotte (Shimaore), is closely related to Swahili and is sometimes considered a dialect of Swahili.

Video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=nOohAUmyb7g

The United Nations has declared 7 July each year as the world’s official day to celebrate the Swahili language. It is the first African language to be recognised by the UN and have its own day of celebration. Swahili is also the only African language to have been officially recognised by the African Union. Swahili, also known by its native name Kiswahili, is a Bantu language and the native language of the Swahili people.The exact number of Swahili speakers, be they native or second-language speakers, is estimated to be between 100 million to 200 million.

In 2018, South Africa legalised the teaching of Swahili in schools as an optional subject to begin in 2020. Botswana followed in 2020, and Namibia plans to introduce the language as well. Shikomor (or Comorian), an official language in Comoros and also spoken in Mayotte (Shimaore), is closely related to Swahili and is sometimes considered a dialect of Swahili.

The Providence Journal

'Fearless' one teacher calls her — East Providence High School student speaks five languages

Linda Borg, The Providence Journal

Fri, January 21, 2022, 4:15 AM

EAST PROVIDENCE — Dilara Ozdemir describes her profound passion for languages — she speaks five, not counting Latin — by quoting the great South African leader Nelson Mandela.

“If you teach a man a language he understands, that will go to his head. If you talk to him in his own language, that goes to his heart.”

Ozdemir came here from Turkey in eighth grade, an observant Muslim who spoke little English but already had a fascination with the sounds of foreign words, which are, after all, a form of music, like birds chatting in the trees.

Dilara Ozdemir of East Providence, a student from Turkey, "will take on any challenge," says Jessica D'Orsi, one of her teachers. "She has this passion for learning about people and culture.”

“When I was three years old, my aunt asked me what the color of a nearby bridge was, and I replied “blue” in English, even though at that time the only language I could speak was Turkish,” Ozdemir wrote in an essay. “When I was five years old, I would claim that I knew Chinese, just because I knew how to say “Ni Hao,” which means “Hello.”

Honored for the 'breadth and depth of her interest in languages'

Last week, Ozdemir was one of two students to receive the Student of the Year award from the Rhode Island Foreign Language Association.

The association wrote, “Ms. Ozdemir impressed the Awards Committee with the breadth and depth of her interest in languages. She has been in the U.S. for four years, learning English, and yet she has taken on Latin, French, American Sign Language, Arabic and Spanish. ... One of her teachers describes her as a 'linguist' who ‘always wants to know more about language — whether discrete grammar points, the etymology of certain words or the connections of language and culture."

The other Student of the Year is Chiara Andrews, a Westerly High School senior who has studied French, Spanish and AP Italian. She is also studying German on her own.

Ozdemir and her family belong to a community called Hizmet, which is dedicated to doing acts of goodwill, such as building schools. In Turkey, the group was reviled by the ruling class and ultimately blamed for staging a coup against President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who then ordered the arrests of women and children and the terrorizing of members of the community, she said.

Worried they might be targeted, Ozdemir’s parents obtained visas and escaped to the United States, where they stayed with a friend in Rhode Island. The family settled in Riverside, which reminds her of her native country because of its proximity to the ocean.

Dilara Ozdemir has applied to 13 colleges and universities, including Brown, Harvard, MIT, Boston College and Wellesley. Math is her major, for now at least.

'She’s fearless and determined'

“Last year, every single day I’d get up and bike for an hour to clear my head,” she said. Thursday. “My family is from the northeast part of Turkey near the Black Sea. It really feels like home here, being near the ocean.”

When Ozdemir arrived, she was assigned to classes for multi-language learners. Today, she is enrolled in three Advanced Placement classes and three honors classes.

Jessica D’Orsi, who teaches English and multi-language learners at East Providence High School, said that in her 15 years of teaching she has never met a student like Ozdemir.

“She’s fearless and determined. What I admire most is she will take on any challenge. She has this passion for learning about people and culture.”

The feeling is mutual. Ozdemir visits Miss D’Orsi every morning.

“She always believed in me,” she said. “I was very stressed out about taking all these AP classes. She told me, ‘You’re going to do fine.’”

Then, D’Orsi told her AP teachers, “Don’t go easy on her. She can do it.”

“We bonded over love of reading,” D’Orsi said. “We shared books.”

A math major — for now

Nothing is too daunting for Ozdemir. She has applied to 13 colleges and universities, including Brown, Harvard, MIT, Boston College and Wellesley. Math is her major, for now at least.

“Until I was eight, I wanted to be a pediatrician. Then I wanted to be a math teacher," she said. “Then I figured I didn’t have the patience to work with kids. I’m thinking of being a math professor now.”

Math has much in common with language: they both have highly structured rules. Math, at its most rarified, approaches poetry.

While it is Ozdemir’s mind that first captures new friends’ attention, it is her heart that leaves the most lasting impression.

One recent Thursday morning, she said hello to a new student and he responded in Turkish, something she taught him.

“One of my biggest dreams is to be able to speak many languages so I can touch people’s hearts," she said. "And this passion of learning languages helps me get closer to my dream every day.”

https://currently.att.yahoo.com/news/fe ... 05255.html

'Fearless' one teacher calls her — East Providence High School student speaks five languages

Linda Borg, The Providence Journal

Fri, January 21, 2022, 4:15 AM

EAST PROVIDENCE — Dilara Ozdemir describes her profound passion for languages — she speaks five, not counting Latin — by quoting the great South African leader Nelson Mandela.

“If you teach a man a language he understands, that will go to his head. If you talk to him in his own language, that goes to his heart.”

Ozdemir came here from Turkey in eighth grade, an observant Muslim who spoke little English but already had a fascination with the sounds of foreign words, which are, after all, a form of music, like birds chatting in the trees.

Dilara Ozdemir of East Providence, a student from Turkey, "will take on any challenge," says Jessica D'Orsi, one of her teachers. "She has this passion for learning about people and culture.”

“When I was three years old, my aunt asked me what the color of a nearby bridge was, and I replied “blue” in English, even though at that time the only language I could speak was Turkish,” Ozdemir wrote in an essay. “When I was five years old, I would claim that I knew Chinese, just because I knew how to say “Ni Hao,” which means “Hello.”

Honored for the 'breadth and depth of her interest in languages'

Last week, Ozdemir was one of two students to receive the Student of the Year award from the Rhode Island Foreign Language Association.

The association wrote, “Ms. Ozdemir impressed the Awards Committee with the breadth and depth of her interest in languages. She has been in the U.S. for four years, learning English, and yet she has taken on Latin, French, American Sign Language, Arabic and Spanish. ... One of her teachers describes her as a 'linguist' who ‘always wants to know more about language — whether discrete grammar points, the etymology of certain words or the connections of language and culture."

The other Student of the Year is Chiara Andrews, a Westerly High School senior who has studied French, Spanish and AP Italian. She is also studying German on her own.

Ozdemir and her family belong to a community called Hizmet, which is dedicated to doing acts of goodwill, such as building schools. In Turkey, the group was reviled by the ruling class and ultimately blamed for staging a coup against President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who then ordered the arrests of women and children and the terrorizing of members of the community, she said.

Worried they might be targeted, Ozdemir’s parents obtained visas and escaped to the United States, where they stayed with a friend in Rhode Island. The family settled in Riverside, which reminds her of her native country because of its proximity to the ocean.

Dilara Ozdemir has applied to 13 colleges and universities, including Brown, Harvard, MIT, Boston College and Wellesley. Math is her major, for now at least.

'She’s fearless and determined'

“Last year, every single day I’d get up and bike for an hour to clear my head,” she said. Thursday. “My family is from the northeast part of Turkey near the Black Sea. It really feels like home here, being near the ocean.”

When Ozdemir arrived, she was assigned to classes for multi-language learners. Today, she is enrolled in three Advanced Placement classes and three honors classes.

Jessica D’Orsi, who teaches English and multi-language learners at East Providence High School, said that in her 15 years of teaching she has never met a student like Ozdemir.

“She’s fearless and determined. What I admire most is she will take on any challenge. She has this passion for learning about people and culture.”

The feeling is mutual. Ozdemir visits Miss D’Orsi every morning.

“She always believed in me,” she said. “I was very stressed out about taking all these AP classes. She told me, ‘You’re going to do fine.’”

Then, D’Orsi told her AP teachers, “Don’t go easy on her. She can do it.”

“We bonded over love of reading,” D’Orsi said. “We shared books.”

A math major — for now

Nothing is too daunting for Ozdemir. She has applied to 13 colleges and universities, including Brown, Harvard, MIT, Boston College and Wellesley. Math is her major, for now at least.

“Until I was eight, I wanted to be a pediatrician. Then I wanted to be a math teacher," she said. “Then I figured I didn’t have the patience to work with kids. I’m thinking of being a math professor now.”

Math has much in common with language: they both have highly structured rules. Math, at its most rarified, approaches poetry.

While it is Ozdemir’s mind that first captures new friends’ attention, it is her heart that leaves the most lasting impression.

One recent Thursday morning, she said hello to a new student and he responded in Turkish, something she taught him.

“One of my biggest dreams is to be able to speak many languages so I can touch people’s hearts," she said. "And this passion of learning languages helps me get closer to my dream every day.”

https://currently.att.yahoo.com/news/fe ... 05255.html

Re: Languages

I Gave Up English for Lent

Last year, I gave up English for Lent. For 40 days, with the exception of conversations, my own activities — the books I read, the television I watched, the podcasts I heard — had to be in one of the non-English languages I could understand, which included Spanish, Portuguese, Korean and Chinese, to varying degrees. As a college senior living in New Jersey at the time, I also made an exception for school; I had to graduate, after all, from a university in a country where English is a necessary part of getting by.