Early Khoja/Ismaili settlements in Africa

Early Khoja/Ismaili settlements in Africa

The Intrepid East Africa Dukawalla:

by: I. I. Dewji, Editor, khojawiki.org (2019)

(You can also read a more detailed version of this article with references, Dukawalla poem and photographs by clicking here)

http://r20.rs6.net/tn.jsp?f=0017adAvrss ... zXPdbSYg==

(Click on the names in brackets (xx) for the personal stories of the dukawallas and other articles in Khojawiki.org)

Ocean Trade - Indian Famines

“The Nizari Khoja had been active as traders between western India and coast Africa at least since the 17th century: the early Indian Nizari immigrants came as well from Kutch, Kathiawar, Surat and Bombay, and settled on Zanzibar Island. By 1820, a small community of Khojas was present in Zanzibar: .." (1)

(See Khoja Shams-ud-din Gillani)

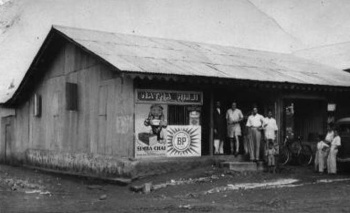

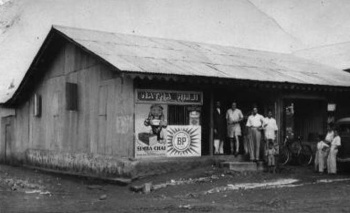

Though Indian merchants were plying the eastern seaboard of Africa from the dawn of history and certainly after the Arab-Muslim conquests (see Zanzibar), the term "Dukawalla" (shopkeeper - derived from the "dukan"- Kutchi for shop) refers to the mainly Khoja/Gujarati migrants who during the Swahili, Omani and European rule in the 19th and 20th century, opened the African hinterland from the coast to the Congo, linking the indigenous inhabitants to the ancient Indian Ocean trade and exports.

Attracted by opportunities created by their caste and family connections and forced out by famines in India in the mid 1800’s, See Gujarat Famines & Khoja Migrations, these Indians migrant families, some peasants themselves from rural Kutch were looking at a hardy future in Africa, often dying of unknown diseases and animals attacks but lured by the stories of rich rewards on the “Zanz” side of the Indian ocean.

See Nathoo Hirji Nathani

Notwithstanding initial mutual apprehension, the dukawallas were universally welcomed by the indigenous Africans who saw them as their windows into the world of fascinating new goods and inventions.

(Read the beautiful poem by Kersi Rustomji "Ode to a Dukawalla on the East African Plain")

Crossing the Kala Pani

In order to create their own “rags to riches” life, the migrants first had to survive a treacherous sea-voyage on ancient Arab dhows, travelling from the ports of Gwadar, Ormara, Mandvi and Muscat to the faraway Mombasa & Zanzibar. The rate of survival was so low and costs of fare was so high that the Gujaratis sorrowfully called this voyage “Crossing the Black Waters”- because those who went rarely returned to India.

After 1914, most travelled from Porbander or Bombay by steamships but even those better constructed European ships were not always safe.

“The coast of East Africa stretches some 4,000 miles from Cape Guardafui in Somalia to the Mozambique Channel. It is rugged and inhospitable, with few safe anchorages, miles of treacherous coral reefs and a strong northerly current. Over the years, it has become a ship’s graveyard to the unlucky ones, and a dire warning to those that ran aground and were subsequently refloated. ..Using records…., the author discovered the stories of over 200 merchant and naval ships that came to grief.” (2)

"Before 1914 and during the two world wars when steamer traffic was interrupted, almost all the Asians came by dhow. Life on these small ships of 80 to 350 tons, 40 to 60 feet long, with wooden hulls and lateen sails, was difficult. The passengers slept on deck and, clustered in groups’ representative of different religious communities, cooked their own food. They had no privacy and lacked any competent medical service. The ships bobbed and rolled off the monsoon seas even in calm weather, and seasickness was common. A storm — and rarely could one escape one or two during the voyage — was a frightening experience.”

“Under the most favorable conditions, the voyage of 2,400 miles to Zanzibar could be made in twenty-six days, but a storm or a calm could extend it by several weeks or even months. Nasser Virji's passage from Kutch in 1875 took nine months.” Sultan Somji, author of "BEAD BAI" provides a more detailed lyrical but terrifying account of one such a voyage in this book.

Caste, Family and Other Assets

If they made it across safely, most Indians started their new life with no capital, having spent the family's meager life savings on the dhow fare.

"Most Asian immigrants arrived penniless…-and looked to relatives to find them jobs with established merchants." (3)

“Once in East Africa, these early immigrants often went through several weeks or months of uncertainty and privation while determining their initial location and employment. Although some had a smattering of English, very few knew any German, Arabic or Kiswahili (4)

The Khoja & other Gujarati migrants had several advantages over other local entrepreneurs. For thousands of years, India has had a well-developed commercial economy and the migrants came equipped with basic skills that proved handy in the new land.

"They were, more than Swahilis, accustomed with a money economy and the concept of interest. In addition, they knew how to read, write and produce account books." (5)

Secondly, being members of ancient trading castes/communities, they had knowledge both of travel and trade. Since the early 1500’s, the Khojas were led by veteran traders and later accomplished Bombay businessmen, whose networks spread from old Mughal ports of Surat, Mandvi & Porbander, the Omani ports of Gwadar & Ormara to Bandar Abbas, Jeddah, Muscat, Bombay, Mombasa, Kilwa and Zanzibar. These strong connections of caste and family provided welcome familiarity and vital support to the Indians in their settlement in East Africa.

(see Ties of the Bandhana by Safder Alladina)

See Hassanali Walji Kanji

“For Indians, particularly recent migrants and those without capital, reliance on kin and patrons for shelter and shop work was an essential step towards autonomy, accumulating capital and establishing one's own business. While it absorbed many migrants, shop hours were long, conditions poor and incomes - though five to ten times more than for African shop workers — were ‘meager’ This period of ‘training’ was later followed by a small salary and perhaps credit or other assistance to set up a shop”. (6)

See Kassamali Hirji Jessani

"This apprenticeship-"service" in the derogatory Gujarati term-was endured until a man could break away, first as itinerant trader and then as resident shopkeeper, taking his stock on credit from a wholesaler" (7)

See Madatally Manji

See Nurmohamed Jiwa Ukani

"Others worked as shopkeepers or clerks for wholesalers [mostly, but not always within the family or community] and started their own business elsewhere in Zanzibar, or one of the other islands, or in the port cities of the mainland. They usually left with their goods, which they had to repay in 90 days.” (8)

For the migrants, the certainty of a path to success was crucial incentive to undertake the dangerous trans-oceanic journey - the established merchants needed outposts to distribute their stock and newly arrived migrants needed immediate work to subsist and send money back to their poorer family. They were motivated and worked hard to prove their worthiness for a loan.

(see Allidina Visram and his relationship of Sewa Haji Paroo)

"Subsequently, the Indian Ismaili moved from Zanzibar to growing urban areas on the east coast of Africa, notably Mombasa, Tanga and Bagamoyo, where they acted as commercial agents for firms in Zanzibar or became petty merchants and shopkeepers.”(9)

See Alarakhia Dossani

The Indian migrants in 1800’s were mostly Kutchis Khoja farmers and labourers lured by the success of merchants travellers such as Taria Toppan and Peera Dewjee and others from Bharapur, Kera etc. who frequently returned home marry etc.

Early 20th century, it was their fellow caste-members, the mostly Gujarati-speaking Khojas of Kathiawar, who were motivated and sometimes recruited by merchants princes like Allidina Visram, Nasser Virji etc.

‘Pioneers like Allidina Visram explored the areas themselves. They established extensive upcountry duka (small shops) networks throughout East Africa and invested in real estate, plantations, shipping and ginneries’.(10)

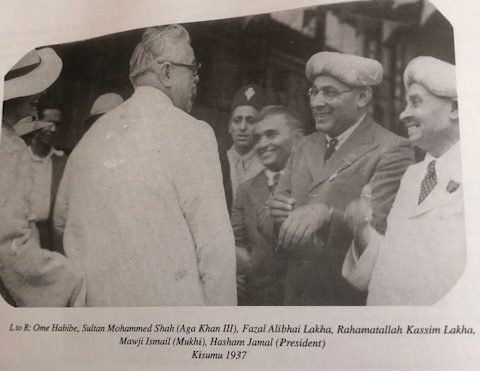

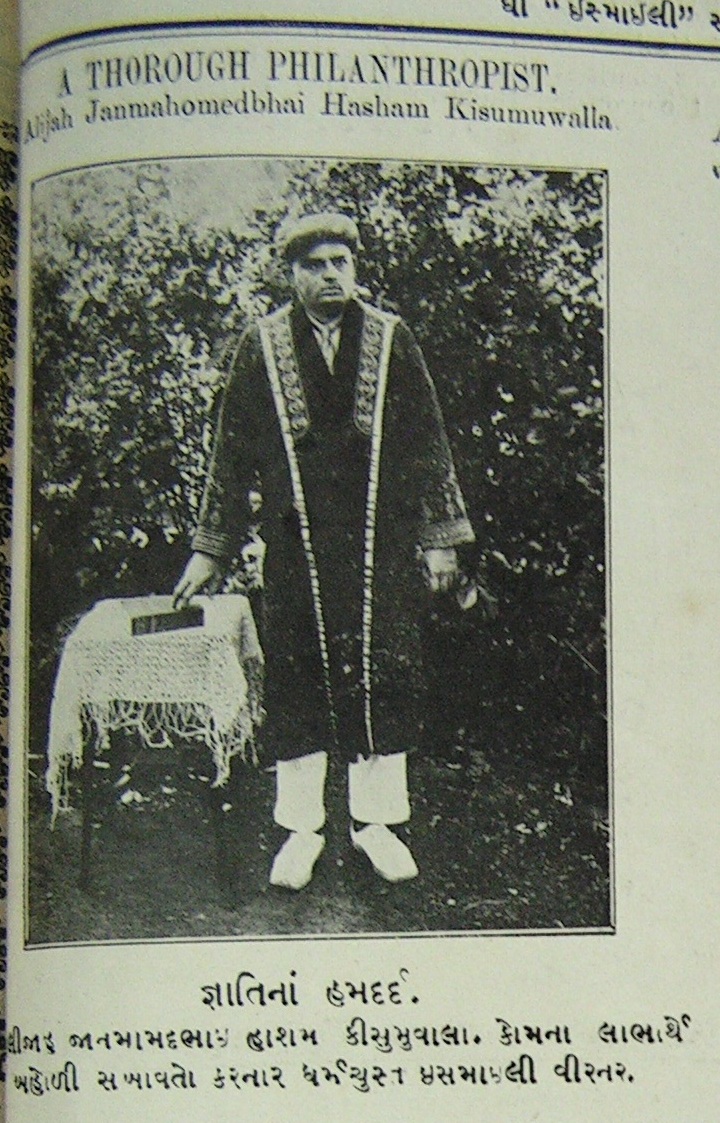

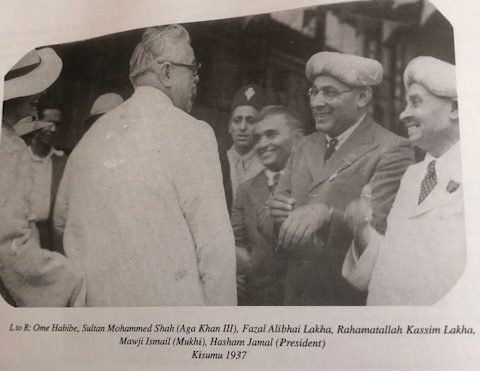

See Hasham Jamal Pradhan

These new migrants (so-called “Nangarias” –possibly because they arrived in steamships with large “nangars” anchors?) were better equipped small traders, retail hawkers and artisans from cities like Jamnagar, Rajkot, Porbander and the many villages of Kathiawar where the Khojas lived in small colonies.

"The immigration to East Africa was therefore a spontaneous one. An enterprising young man who wanted to emigrate had to find his own fare across the ocean or persuade a relative already established in Africa to pay it and help him on arrival. For this reason the poorest classes in India did not come to East Africa, nor did the rich and well-educated. In addition, only those living reasonably close to convenient ports were likely to make the journey. Consequently the Indian immigrants to East Africa were not usually unskilled labourers, as were the Indian settlers in South Africa, Mauritius, Fiji, and the West Indies, who had been recruited for plantation labour in tropical agricultural colonies. The East African settlers were mainly petty traders and artisans, and though most of them came from a background of village and farm, almost none took to farming, in spite of the hope of the administration of the East African Protectorate at the beginning of this century that they might." (11)

To find a suitable location for their own duka, they followed the earlier Khoja merchant-traders, who had had worked along the old Arab caravan trade inland from Bagamoyo.

"The South Asian Khojas, Tharia Thopan (1823-?), Sewji Haji (1851-1997), Allidina Visram (1851-1916) and Nasser Veerjee (1865-1942), were among the principal financiers of caravan traders in the late nineteenth century. Most of them managed their businesses from the coast, but they gathered first-hand information on the inland trade routes". (12)

The earliest record of a Khoja dukawalla/trader in the interior is Musa Kanji (or Musa Mzuri – “Musa, the Good”, as he was called by the European explorers such as Grant), who was said have lived in Tabora from the 1840’s. Many Khojas can trace their ancestors to Bagamoyo, Tabora (known then as Kazeh) or Kigoma (known then as Ujiji) as well as Mwanza and Bukoba, which were old Swahili/Arab settlements in the interior.

After 1890, the German started to build a string of “Bomas” administrative centres across their new colony and the Dukawalla generally set up shop nearby so as have maximum security during the bloody colonisation period. It is reported that over 1000 traders followed the German Major Prince when he moved to the Iringa & Tukuyu area.

(See Gulamhusein Moloo Hirji)

In 1910, the Germans started building the “Central Railway” and the Indian dukawallas helped to create towns like Morogoro, Dodoma and Kigoma. Arusha & Moshi were the result of the German-built Usambara Railway system.

“Whereas in 1901 only 58 of 3,420 Asians are known to have lived in interior districts, by 1912 the figure was 8,591 out of 8,698. German administrative centres attracted storekeepers.".(13)

Across the border in the East African Protectorate, when the British started building the Uganda Railway from Mombasa in 1891, the rail-head stations made convenient trading posts for the Dukawallas, who were set-up by the merchant princes like Allidina Visram and others.

“By the 1870, there were some 2,500 Ismaili Khojas in East Africa and their ranks swelled even further after the establishment of the British Protectorate in 1891 (i.e. Kenya and Uganda, Editor.) "(14)

see Mohamed Manek

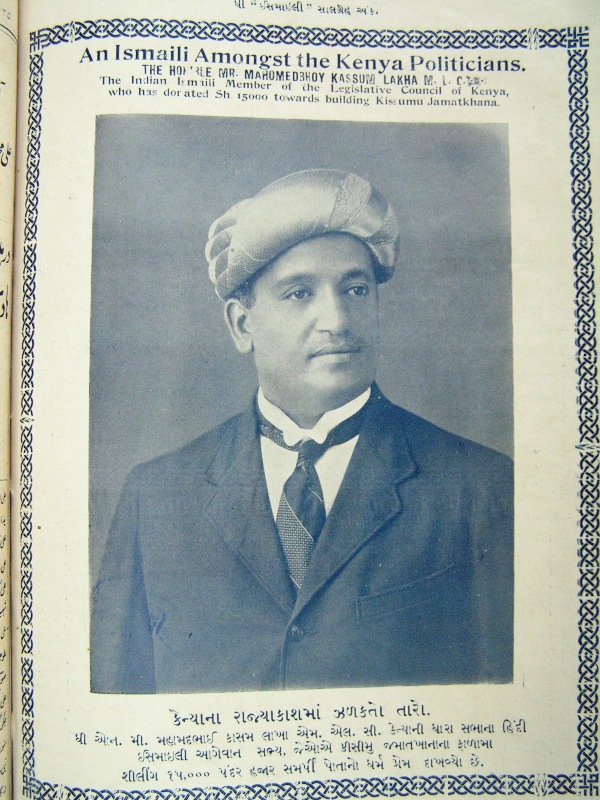

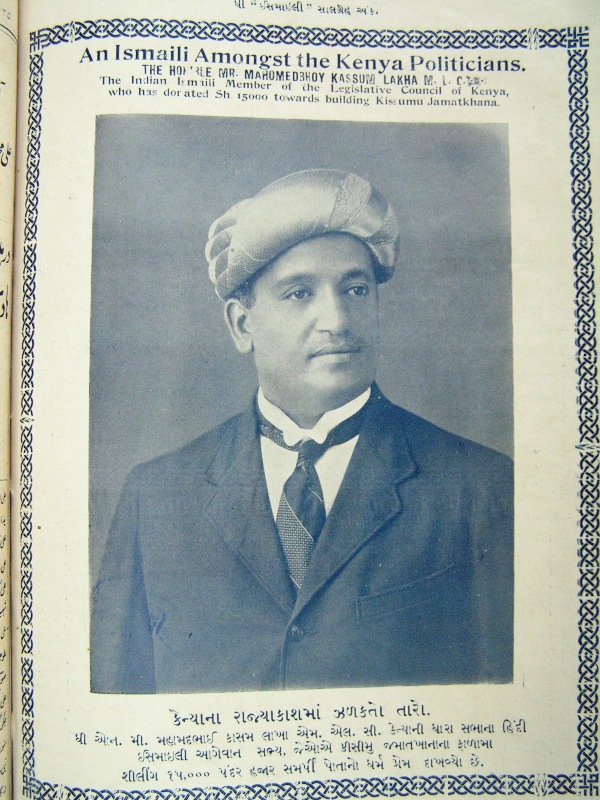

see Kassim Lakha

The dukawallas also moved into the unexplored hinterland setting up mud and corrugated iron shops in villages at the edge of civilization providing rations and essentials of life to the indigenous peasants and in the towns to German & British administrators.

See Kersi Rustomji's wonderful poem for a detailed description of the amazing array of goods and experiences they brought to the indigenous Africans..

See Mohamedali Remtulla Mulji

The Dukawallas were able to endure the lonely bush-life by taking solace that by escaping poverty & famine, they were able to provide for their families. The Omani Sultans who had first welcomed them in Muscat & Gwadar and later in Zanzibar were Ibadi Muslims, a minority sect with a centuries-old history of Indian Ocean trading and tolerance of the smorgasbord of the Indian faith systems. The Khojas and other Gujarati migrants, being members of ancient Indian spiritual communities, practised their dharma (faith) through “sewa” volunteer service within their respective castes in these small towns in East Africa. (Later, after Independence, this entrenched communalism born out of necessity, but from a different era, became a ground for resentment by some indigenous Africans.)

For a detailed account of Khoja dukawalla family life, read Sultan Somji’s two books, “Bead Bai” and “The Crossing”.

see see Fatmabai Kasssamali Kanji Bhatia

Earn Credit - Give Credit

The dukawallas ultimate business success lay in continually seeking new opportunities in the expanding economies, due to the systemic exploitation of the natural resources of the colonies by the Europeans.

“All Indian businesses.....relied heavily on credit systems. Supply-line credit from European and Indian merchant houses, often based on ninety-day terms, stretched from the docks of Dar es Salaam to the smallest rural shops. ." (15)

(see Dolatkhanu Alibhai Gulamhussien Jiwani )

(see Zerakhanu Rajabali Fazal Alidina)

“Therefore, the most important ‘security’ was a person’s ‘good name’. A ‘good name’ was gained by repaying debts in time, being known among credit worthy people, and being an honest and trustworthy businessman in general. If a family’s reputation was lost, it would be very difficult to obtain new credits." '(16)

See see Hasham Jamal Pradhan

(Interestingly, back in India in the 1870’s, on the foothills of the Himalayas’ near Simla, Khoja itinerant traders were bringing merchandise from the Bombay & Delhi merchants and similarly distributing them to farmers on credit. The peddlers worked in groups and if one defaulted, the others were responsible for those debts. It would appear that a “good name” ethic was long entrenched in the Khoja business practices) (17)

The Dukawallas’ genius was to create methodologies to extend similar credit to their indigenous customers and successfully bringing them into the cash economy.

"In one common practice known as amana, Indian retailers extended credit in return for offering safe deposit of African goods or money, usually accumulated from a dowry or crop sale, which would subsequently serve as a surety for monthly store credit." (18)

Later, this spawned into the business of "pawn-shops" which became part of the retail nexus providing a vital business service in the harsh colonial system.

"...such shops also provided the nexus for the distribution of basic necessities such as food and clothing to those living month-to-month on credit margins." (19)

(See see Nurbanu Dharamsi Rawji)

"Credit was universally available at pawnshops, which in Dar es Salaam were owned entirely by Khoja Ismaili Indians, and intimately connected with most African household economics. Pledges peaked from the twentieth to the end of each month, during siku za mwambo “tight-stretched days.” Upon wage payments on the first of the month, each pawnshop in town would attend to between three and four hundred customers who queued to redeem their goods." (20)

In the countryside, another growth opportunity was a consequence of the Khoja tradition of not adopting the Muslim “purdah” for their women. As soon a new Khoja bride became adept in KiSwahili, the Dukawalla was able to leave the shop to her and go on buying sprees for local produce & artisan products and ship them to the larger urban markets. This was an important economic advantage over other Muslims and Hindus traders whose tradition was of not involving their spouses in business.

see Maherali Gokal Versi

Business Risks - Colonial Hostility

However, as Brennan points out, there were also substantial obstacles to success in retail for these small vyaparis businessmen (Later, this term was corrupted into the derogatory KiSwahili “Bepari” exploiter and used against the Indians)

"The system functioned on high turnover and small cash margins—often as little as 10 percent — offering higher profits but greater risks and frequent bankruptcies among small Indian traders." (21)

see Gulamali JIna Madhavji

"Last but not least, (5) the success of South Asian businessmen in East Africa was the outcome of a ‘trial and error’ process." (22)

see Rahemtulla Walji Virji

Gijsbert Oonk study of bankruptcies in early Zanzibar show that as many as 50% of the businesses failed in the first instance and also that failure meant a very slow route up if they wanted to access the community network of credit again.

“Therefore, it is not surprising that family members would take the responsibility for the debts of fathers, brothers, or in-laws, even if they were not legally obliged to do so. In these cases, keeping up the family name was of high priority in order to attract new or future investors.” (23)

Underlying this struggle to succeed was the insidious racism of the colonial order. The East African dukawalla endured constant harassment at hands of the European masters.

"In 1913, the Bombay Chronicle published an analysis and fierce criticism of the discriminatory policies in the British East African Protectorate (present day Kenya& Uganda: Editor). The article initially highlights the economic and political contribution of South Asians in East Africa, but then cynically stresses:

And now the Indian cannot acquire property in the uplands, cannot carry weapons, cannot enter the Market House in Nairobi, cannot travel in comfort on the steamers and railways, cannot have a trial by jury, in short cannot be anything else than an undesirable alien [emphasis added].

It is clear from the newspaper article that while the Germans and the British were colonising East Africa, they were also alienating the South Asians who lived there. Many South Asian traders and businessmen believed that due to discriminatory regulations, they were unable to compete with Europeans on an equal basis. At the same time, they were not able to defend their properties and protect their families, despite the fact that most of them were British subjects" 24)

"The writer's father, W. H. King, who fought here with the Indian Expeditionary Force from 1915 to 1918. used to say that the whole natural line of business communication between Tanga and Mombasa, Arusha and Nairobi, Kisumu and its southwestern hinterland was broken up. He described the sufferings of the indian duka keepers who were merrily raided by both sides as the battle ebbed and flowed. The Belgians coming in from the Congo into Rwanda and Burundi and then crossing the lake to push towards Tabora treated the Indian traders in the same way as they advanced and the Germans retreated" (25)

see Mohamed Dewji

see Kassam HAJI

Sir Yusufali Karimjee, speaking for Indians in Tanganyika put it well: "The policy of the Government underlying this movement is to rob Indian Peter to pay British Paul" (26)

Visible Everywhere-Invisible in History

East African cities, towns and villages display the large and indelible presence of the Indians - in the markets areas, in the urban buildings, in the residential suburbs, in the foods and in the public infrastructure.

"South Asians in East Africa are written out of history. They do not play an important part in the textbooks on Tanzanian, Kenyan and Ugandan history. In fact, if they are mentioned at all, they are seen as a part of people who were expelled and did not play an important part in the national histories. Furthermore, they are not part of the Indian national history as they migrated before India became independent. Finally, they are not part of the European colonial history, except for being ‘middlemen’ who could be employed for the colonial projects." (27)

The East African Dukawalla has been, for at least 150 years, a portrait of personal sacrifice and dogged tenacity. Maligned by ungrateful colonials and opportunists’ indigenous politicians, it is fitting that as Africans finally take their proper place in the world, this laudable story of endurance and enterprise by those who paved the way, is properly told.

------------------

From Khojawiki.org:

WHAT IS KHOJAWIKI.ORG

The Khoja Diaspora

We believe, as many of you also do that the incredible 700-year migratory history of the Khojas should not be allowed to die even I'd our elders pass away. Our response is Khojawiki.org - a not-for-profit collaborative effort to systematically record living people's stories about their own experiences and their recollection of the stories of their parents and other ancestors in their own words, using the power of the Internet.

-----------

On their main page, you can read from:

INDEX OF OVER 250 PERSONAL HISTORIES IN KHOJAWIKI

by: I. I. Dewji, Editor, khojawiki.org (2019)

(You can also read a more detailed version of this article with references, Dukawalla poem and photographs by clicking here)

http://r20.rs6.net/tn.jsp?f=0017adAvrss ... zXPdbSYg==

(Click on the names in brackets (xx) for the personal stories of the dukawallas and other articles in Khojawiki.org)

Ocean Trade - Indian Famines

“The Nizari Khoja had been active as traders between western India and coast Africa at least since the 17th century: the early Indian Nizari immigrants came as well from Kutch, Kathiawar, Surat and Bombay, and settled on Zanzibar Island. By 1820, a small community of Khojas was present in Zanzibar: .." (1)

(See Khoja Shams-ud-din Gillani)

Though Indian merchants were plying the eastern seaboard of Africa from the dawn of history and certainly after the Arab-Muslim conquests (see Zanzibar), the term "Dukawalla" (shopkeeper - derived from the "dukan"- Kutchi for shop) refers to the mainly Khoja/Gujarati migrants who during the Swahili, Omani and European rule in the 19th and 20th century, opened the African hinterland from the coast to the Congo, linking the indigenous inhabitants to the ancient Indian Ocean trade and exports.

Attracted by opportunities created by their caste and family connections and forced out by famines in India in the mid 1800’s, See Gujarat Famines & Khoja Migrations, these Indians migrant families, some peasants themselves from rural Kutch were looking at a hardy future in Africa, often dying of unknown diseases and animals attacks but lured by the stories of rich rewards on the “Zanz” side of the Indian ocean.

See Nathoo Hirji Nathani

Notwithstanding initial mutual apprehension, the dukawallas were universally welcomed by the indigenous Africans who saw them as their windows into the world of fascinating new goods and inventions.

(Read the beautiful poem by Kersi Rustomji "Ode to a Dukawalla on the East African Plain")

Crossing the Kala Pani

In order to create their own “rags to riches” life, the migrants first had to survive a treacherous sea-voyage on ancient Arab dhows, travelling from the ports of Gwadar, Ormara, Mandvi and Muscat to the faraway Mombasa & Zanzibar. The rate of survival was so low and costs of fare was so high that the Gujaratis sorrowfully called this voyage “Crossing the Black Waters”- because those who went rarely returned to India.

After 1914, most travelled from Porbander or Bombay by steamships but even those better constructed European ships were not always safe.

“The coast of East Africa stretches some 4,000 miles from Cape Guardafui in Somalia to the Mozambique Channel. It is rugged and inhospitable, with few safe anchorages, miles of treacherous coral reefs and a strong northerly current. Over the years, it has become a ship’s graveyard to the unlucky ones, and a dire warning to those that ran aground and were subsequently refloated. ..Using records…., the author discovered the stories of over 200 merchant and naval ships that came to grief.” (2)

"Before 1914 and during the two world wars when steamer traffic was interrupted, almost all the Asians came by dhow. Life on these small ships of 80 to 350 tons, 40 to 60 feet long, with wooden hulls and lateen sails, was difficult. The passengers slept on deck and, clustered in groups’ representative of different religious communities, cooked their own food. They had no privacy and lacked any competent medical service. The ships bobbed and rolled off the monsoon seas even in calm weather, and seasickness was common. A storm — and rarely could one escape one or two during the voyage — was a frightening experience.”

“Under the most favorable conditions, the voyage of 2,400 miles to Zanzibar could be made in twenty-six days, but a storm or a calm could extend it by several weeks or even months. Nasser Virji's passage from Kutch in 1875 took nine months.” Sultan Somji, author of "BEAD BAI" provides a more detailed lyrical but terrifying account of one such a voyage in this book.

Caste, Family and Other Assets

If they made it across safely, most Indians started their new life with no capital, having spent the family's meager life savings on the dhow fare.

"Most Asian immigrants arrived penniless…-and looked to relatives to find them jobs with established merchants." (3)

“Once in East Africa, these early immigrants often went through several weeks or months of uncertainty and privation while determining their initial location and employment. Although some had a smattering of English, very few knew any German, Arabic or Kiswahili (4)

The Khoja & other Gujarati migrants had several advantages over other local entrepreneurs. For thousands of years, India has had a well-developed commercial economy and the migrants came equipped with basic skills that proved handy in the new land.

"They were, more than Swahilis, accustomed with a money economy and the concept of interest. In addition, they knew how to read, write and produce account books." (5)

Secondly, being members of ancient trading castes/communities, they had knowledge both of travel and trade. Since the early 1500’s, the Khojas were led by veteran traders and later accomplished Bombay businessmen, whose networks spread from old Mughal ports of Surat, Mandvi & Porbander, the Omani ports of Gwadar & Ormara to Bandar Abbas, Jeddah, Muscat, Bombay, Mombasa, Kilwa and Zanzibar. These strong connections of caste and family provided welcome familiarity and vital support to the Indians in their settlement in East Africa.

(see Ties of the Bandhana by Safder Alladina)

See Hassanali Walji Kanji

“For Indians, particularly recent migrants and those without capital, reliance on kin and patrons for shelter and shop work was an essential step towards autonomy, accumulating capital and establishing one's own business. While it absorbed many migrants, shop hours were long, conditions poor and incomes - though five to ten times more than for African shop workers — were ‘meager’ This period of ‘training’ was later followed by a small salary and perhaps credit or other assistance to set up a shop”. (6)

See Kassamali Hirji Jessani

"This apprenticeship-"service" in the derogatory Gujarati term-was endured until a man could break away, first as itinerant trader and then as resident shopkeeper, taking his stock on credit from a wholesaler" (7)

See Madatally Manji

See Nurmohamed Jiwa Ukani

"Others worked as shopkeepers or clerks for wholesalers [mostly, but not always within the family or community] and started their own business elsewhere in Zanzibar, or one of the other islands, or in the port cities of the mainland. They usually left with their goods, which they had to repay in 90 days.” (8)

For the migrants, the certainty of a path to success was crucial incentive to undertake the dangerous trans-oceanic journey - the established merchants needed outposts to distribute their stock and newly arrived migrants needed immediate work to subsist and send money back to their poorer family. They were motivated and worked hard to prove their worthiness for a loan.

(see Allidina Visram and his relationship of Sewa Haji Paroo)

"Subsequently, the Indian Ismaili moved from Zanzibar to growing urban areas on the east coast of Africa, notably Mombasa, Tanga and Bagamoyo, where they acted as commercial agents for firms in Zanzibar or became petty merchants and shopkeepers.”(9)

See Alarakhia Dossani

The Indian migrants in 1800’s were mostly Kutchis Khoja farmers and labourers lured by the success of merchants travellers such as Taria Toppan and Peera Dewjee and others from Bharapur, Kera etc. who frequently returned home marry etc.

Early 20th century, it was their fellow caste-members, the mostly Gujarati-speaking Khojas of Kathiawar, who were motivated and sometimes recruited by merchants princes like Allidina Visram, Nasser Virji etc.

‘Pioneers like Allidina Visram explored the areas themselves. They established extensive upcountry duka (small shops) networks throughout East Africa and invested in real estate, plantations, shipping and ginneries’.(10)

See Hasham Jamal Pradhan

These new migrants (so-called “Nangarias” –possibly because they arrived in steamships with large “nangars” anchors?) were better equipped small traders, retail hawkers and artisans from cities like Jamnagar, Rajkot, Porbander and the many villages of Kathiawar where the Khojas lived in small colonies.

"The immigration to East Africa was therefore a spontaneous one. An enterprising young man who wanted to emigrate had to find his own fare across the ocean or persuade a relative already established in Africa to pay it and help him on arrival. For this reason the poorest classes in India did not come to East Africa, nor did the rich and well-educated. In addition, only those living reasonably close to convenient ports were likely to make the journey. Consequently the Indian immigrants to East Africa were not usually unskilled labourers, as were the Indian settlers in South Africa, Mauritius, Fiji, and the West Indies, who had been recruited for plantation labour in tropical agricultural colonies. The East African settlers were mainly petty traders and artisans, and though most of them came from a background of village and farm, almost none took to farming, in spite of the hope of the administration of the East African Protectorate at the beginning of this century that they might." (11)

To find a suitable location for their own duka, they followed the earlier Khoja merchant-traders, who had had worked along the old Arab caravan trade inland from Bagamoyo.

"The South Asian Khojas, Tharia Thopan (1823-?), Sewji Haji (1851-1997), Allidina Visram (1851-1916) and Nasser Veerjee (1865-1942), were among the principal financiers of caravan traders in the late nineteenth century. Most of them managed their businesses from the coast, but they gathered first-hand information on the inland trade routes". (12)

The earliest record of a Khoja dukawalla/trader in the interior is Musa Kanji (or Musa Mzuri – “Musa, the Good”, as he was called by the European explorers such as Grant), who was said have lived in Tabora from the 1840’s. Many Khojas can trace their ancestors to Bagamoyo, Tabora (known then as Kazeh) or Kigoma (known then as Ujiji) as well as Mwanza and Bukoba, which were old Swahili/Arab settlements in the interior.

After 1890, the German started to build a string of “Bomas” administrative centres across their new colony and the Dukawalla generally set up shop nearby so as have maximum security during the bloody colonisation period. It is reported that over 1000 traders followed the German Major Prince when he moved to the Iringa & Tukuyu area.

(See Gulamhusein Moloo Hirji)

In 1910, the Germans started building the “Central Railway” and the Indian dukawallas helped to create towns like Morogoro, Dodoma and Kigoma. Arusha & Moshi were the result of the German-built Usambara Railway system.

“Whereas in 1901 only 58 of 3,420 Asians are known to have lived in interior districts, by 1912 the figure was 8,591 out of 8,698. German administrative centres attracted storekeepers.".(13)

Across the border in the East African Protectorate, when the British started building the Uganda Railway from Mombasa in 1891, the rail-head stations made convenient trading posts for the Dukawallas, who were set-up by the merchant princes like Allidina Visram and others.

“By the 1870, there were some 2,500 Ismaili Khojas in East Africa and their ranks swelled even further after the establishment of the British Protectorate in 1891 (i.e. Kenya and Uganda, Editor.) "(14)

see Mohamed Manek

see Kassim Lakha

The dukawallas also moved into the unexplored hinterland setting up mud and corrugated iron shops in villages at the edge of civilization providing rations and essentials of life to the indigenous peasants and in the towns to German & British administrators.

See Kersi Rustomji's wonderful poem for a detailed description of the amazing array of goods and experiences they brought to the indigenous Africans..

See Mohamedali Remtulla Mulji

The Dukawallas were able to endure the lonely bush-life by taking solace that by escaping poverty & famine, they were able to provide for their families. The Omani Sultans who had first welcomed them in Muscat & Gwadar and later in Zanzibar were Ibadi Muslims, a minority sect with a centuries-old history of Indian Ocean trading and tolerance of the smorgasbord of the Indian faith systems. The Khojas and other Gujarati migrants, being members of ancient Indian spiritual communities, practised their dharma (faith) through “sewa” volunteer service within their respective castes in these small towns in East Africa. (Later, after Independence, this entrenched communalism born out of necessity, but from a different era, became a ground for resentment by some indigenous Africans.)

For a detailed account of Khoja dukawalla family life, read Sultan Somji’s two books, “Bead Bai” and “The Crossing”.

see see Fatmabai Kasssamali Kanji Bhatia

Earn Credit - Give Credit

The dukawallas ultimate business success lay in continually seeking new opportunities in the expanding economies, due to the systemic exploitation of the natural resources of the colonies by the Europeans.

“All Indian businesses.....relied heavily on credit systems. Supply-line credit from European and Indian merchant houses, often based on ninety-day terms, stretched from the docks of Dar es Salaam to the smallest rural shops. ." (15)

(see Dolatkhanu Alibhai Gulamhussien Jiwani )

(see Zerakhanu Rajabali Fazal Alidina)

“Therefore, the most important ‘security’ was a person’s ‘good name’. A ‘good name’ was gained by repaying debts in time, being known among credit worthy people, and being an honest and trustworthy businessman in general. If a family’s reputation was lost, it would be very difficult to obtain new credits." '(16)

See see Hasham Jamal Pradhan

(Interestingly, back in India in the 1870’s, on the foothills of the Himalayas’ near Simla, Khoja itinerant traders were bringing merchandise from the Bombay & Delhi merchants and similarly distributing them to farmers on credit. The peddlers worked in groups and if one defaulted, the others were responsible for those debts. It would appear that a “good name” ethic was long entrenched in the Khoja business practices) (17)

The Dukawallas’ genius was to create methodologies to extend similar credit to their indigenous customers and successfully bringing them into the cash economy.

"In one common practice known as amana, Indian retailers extended credit in return for offering safe deposit of African goods or money, usually accumulated from a dowry or crop sale, which would subsequently serve as a surety for monthly store credit." (18)

Later, this spawned into the business of "pawn-shops" which became part of the retail nexus providing a vital business service in the harsh colonial system.

"...such shops also provided the nexus for the distribution of basic necessities such as food and clothing to those living month-to-month on credit margins." (19)

(See see Nurbanu Dharamsi Rawji)

"Credit was universally available at pawnshops, which in Dar es Salaam were owned entirely by Khoja Ismaili Indians, and intimately connected with most African household economics. Pledges peaked from the twentieth to the end of each month, during siku za mwambo “tight-stretched days.” Upon wage payments on the first of the month, each pawnshop in town would attend to between three and four hundred customers who queued to redeem their goods." (20)

In the countryside, another growth opportunity was a consequence of the Khoja tradition of not adopting the Muslim “purdah” for their women. As soon a new Khoja bride became adept in KiSwahili, the Dukawalla was able to leave the shop to her and go on buying sprees for local produce & artisan products and ship them to the larger urban markets. This was an important economic advantage over other Muslims and Hindus traders whose tradition was of not involving their spouses in business.

see Maherali Gokal Versi

Business Risks - Colonial Hostility

However, as Brennan points out, there were also substantial obstacles to success in retail for these small vyaparis businessmen (Later, this term was corrupted into the derogatory KiSwahili “Bepari” exploiter and used against the Indians)

"The system functioned on high turnover and small cash margins—often as little as 10 percent — offering higher profits but greater risks and frequent bankruptcies among small Indian traders." (21)

see Gulamali JIna Madhavji

"Last but not least, (5) the success of South Asian businessmen in East Africa was the outcome of a ‘trial and error’ process." (22)

see Rahemtulla Walji Virji

Gijsbert Oonk study of bankruptcies in early Zanzibar show that as many as 50% of the businesses failed in the first instance and also that failure meant a very slow route up if they wanted to access the community network of credit again.

“Therefore, it is not surprising that family members would take the responsibility for the debts of fathers, brothers, or in-laws, even if they were not legally obliged to do so. In these cases, keeping up the family name was of high priority in order to attract new or future investors.” (23)

Underlying this struggle to succeed was the insidious racism of the colonial order. The East African dukawalla endured constant harassment at hands of the European masters.

"In 1913, the Bombay Chronicle published an analysis and fierce criticism of the discriminatory policies in the British East African Protectorate (present day Kenya& Uganda: Editor). The article initially highlights the economic and political contribution of South Asians in East Africa, but then cynically stresses:

And now the Indian cannot acquire property in the uplands, cannot carry weapons, cannot enter the Market House in Nairobi, cannot travel in comfort on the steamers and railways, cannot have a trial by jury, in short cannot be anything else than an undesirable alien [emphasis added].

It is clear from the newspaper article that while the Germans and the British were colonising East Africa, they were also alienating the South Asians who lived there. Many South Asian traders and businessmen believed that due to discriminatory regulations, they were unable to compete with Europeans on an equal basis. At the same time, they were not able to defend their properties and protect their families, despite the fact that most of them were British subjects" 24)

"The writer's father, W. H. King, who fought here with the Indian Expeditionary Force from 1915 to 1918. used to say that the whole natural line of business communication between Tanga and Mombasa, Arusha and Nairobi, Kisumu and its southwestern hinterland was broken up. He described the sufferings of the indian duka keepers who were merrily raided by both sides as the battle ebbed and flowed. The Belgians coming in from the Congo into Rwanda and Burundi and then crossing the lake to push towards Tabora treated the Indian traders in the same way as they advanced and the Germans retreated" (25)

see Mohamed Dewji

see Kassam HAJI

Sir Yusufali Karimjee, speaking for Indians in Tanganyika put it well: "The policy of the Government underlying this movement is to rob Indian Peter to pay British Paul" (26)

Visible Everywhere-Invisible in History

East African cities, towns and villages display the large and indelible presence of the Indians - in the markets areas, in the urban buildings, in the residential suburbs, in the foods and in the public infrastructure.

"South Asians in East Africa are written out of history. They do not play an important part in the textbooks on Tanzanian, Kenyan and Ugandan history. In fact, if they are mentioned at all, they are seen as a part of people who were expelled and did not play an important part in the national histories. Furthermore, they are not part of the Indian national history as they migrated before India became independent. Finally, they are not part of the European colonial history, except for being ‘middlemen’ who could be employed for the colonial projects." (27)

The East African Dukawalla has been, for at least 150 years, a portrait of personal sacrifice and dogged tenacity. Maligned by ungrateful colonials and opportunists’ indigenous politicians, it is fitting that as Africans finally take their proper place in the world, this laudable story of endurance and enterprise by those who paved the way, is properly told.

------------------

From Khojawiki.org:

WHAT IS KHOJAWIKI.ORG

The Khoja Diaspora

We believe, as many of you also do that the incredible 700-year migratory history of the Khojas should not be allowed to die even I'd our elders pass away. Our response is Khojawiki.org - a not-for-profit collaborative effort to systematically record living people's stories about their own experiences and their recollection of the stories of their parents and other ancestors in their own words, using the power of the Internet.

-----------

On their main page, you can read from:

INDEX OF OVER 250 PERSONAL HISTORIES IN KHOJAWIKI

Early Ismaili settlers of East Africa established a foothold in Zanzibar

Posted by Nimira Dewji

The archipelago of Zanzibar comprising two main islands (Unguja – commonly known as Zanzibar and Pemba) and several smaller ones, has been inhabited for over 20,000 years when the island served as a gateway for traders between the African Great Lakes, the Arabian Peninsula, the Indian subcontinent, and Europe.

In 1503, Zanzibar became part of the Portuguese Empire for almost 200 years. In 1698, Zanzibar came under the reign of the Sultanate of Oman, and subsequently under British rule in 1890. The island became independent in 1963, joining Tanganyika in the following year to form the Republic of Tanzania.

Zanzibar

Encyclopaedia Britannica

Several communities began to migrate to Zanzibar in the seventh century; the earliest immigrants were Africans followed by Arabs. The Persians, mostly from the city of Shiraz, began to arrive in the tenth century and, over time, became absorbed into the local population. The African-Persian population, who adopted many Persian traditions, came to be known as Shirazi.

Early Ismaili Settlers

The earliest Nizari Ismailis to immigrate to East Africa from the Indian subcontinent first established their foothold in Zanzibar in the 1800s although Ismaili merchants and other traders based in western India had been trading in western Indian Ocean since at least the seventeenth century. Traders used the northeast monsoon winds to travel across the Indian Ocean with their merchandise, often at sea for a month or longer in harsh conditions. When the monsoon winds changed direction to southwest, traders returned home with their wares.

The early Ismailis settlers in Zanzibar were farmers, who were compelled to immigrate due to successive droughts and famines that had caused economic hardships, also provoked by British industrialisation and economic policies. Eventually large numbers of community members of diverse backgrounds began to migrate. When Zanzibar became the Omani capital in 1832, it provided political stability and security as well as enhanced economic opportunities for traders to expand their businesses. India-based merchants became politically and economically important for the local rulers who appointed many of them to the post of chief customs inspectors, including Tharia Topan (d. 1891), Allidina Visram (d. 1916), and others.

Zanzibar Ismailis topan aga khan

Sultan Sayyed Bargash bin Said (d. 1888) seated, centre, with members of his court including Sir Tharia Topan (d. 1891) standing, centre. who served as the Sultan’s chief customs officer and was given the honorary title of Prime Minister of Zanzibar. Source: The Ismailis An Illustrated History

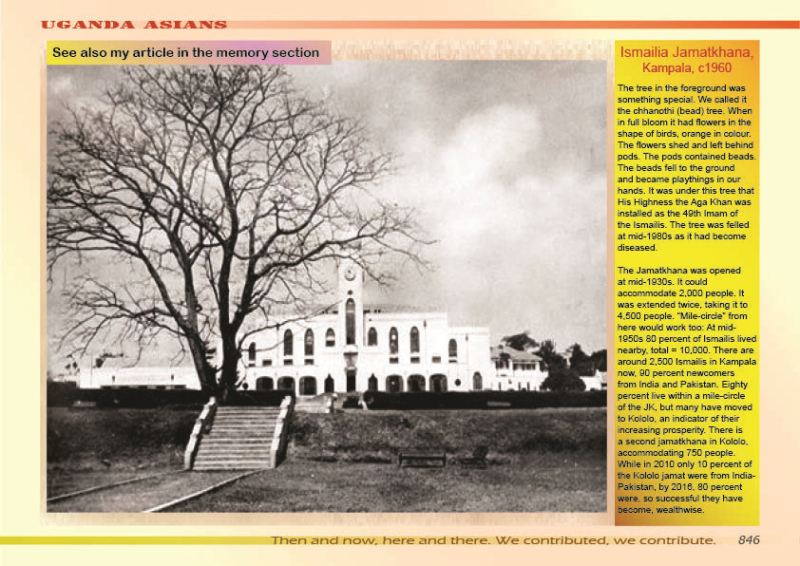

The first Nizari Ismaili jamatkhana in Zanzibar was established in the 1830s, with the appointments of mukhis and kamadias, during the time of the forty-sixth Imam Hasan Ali Shah Aga Khan I (1804-1881). The darkhana of Zanzibar was officially opened by Imam Sultan Muhammed Shah (1877-1957) on August 16, 1905.

jamatkhana zanzibar east africa

Zanzibar jamatkhana. Source: Khojawiki

Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah also issued the first Ismaili Constitution in 1905, in Gujarati, under the title Khoja Shia Imami Ismaili Counsilna Kayadani Book: Prakaran Pelu thata Biju (The Rule Book of the Khoja Shia Imami Ismaili Council: Parts 1 and 2). This document was instituted along with the first Supreme Council for Africa.

Ismaili Constitution

Front inside cover of the Ismaili Constitution issued at Zanzibar in 1905. Photo: The Ismailis An Illustrated History.

Sultan Muhammad Shah Aga Khan III Zanzibar

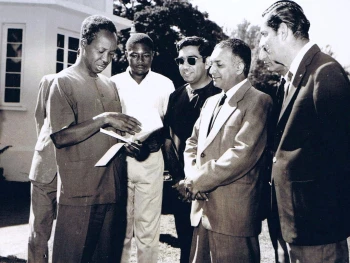

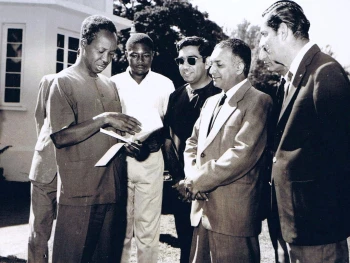

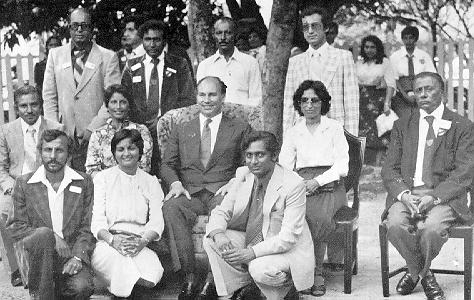

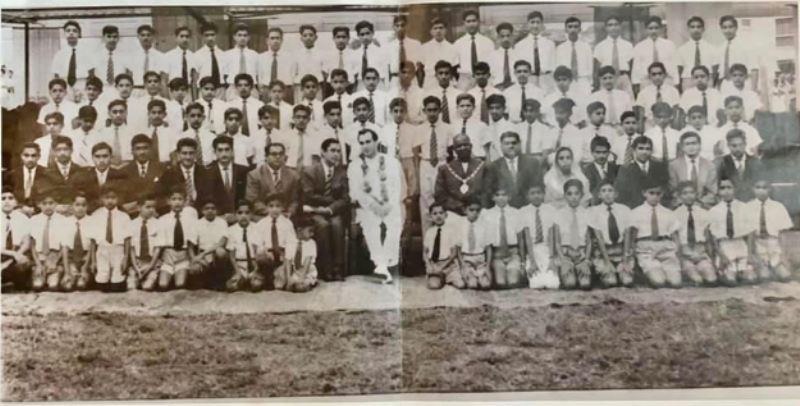

First Supreme Council for Africa. Photo: The Ismailis An Illustrated History left to right: Top, standing: Mohamed Bhanji, Gulamhusein Harji Sumar Muhamed Rashid Alana, Ali Valli Issa, Gulamhussein Karmali Bhaloo Middle, seated: Pirmohamed Kanji, Visram Harji, President Vizier Mohamed Rahemtulla Hemani, Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah al-Husayni Aga Khan III, Fazal Essani, Gulamhusien Bhaloo Kurji. Bottom row, seated: Mukhi Rajabali Gangji, Vizier Kassam Damani, Janmohamed Hansraj, Rai Mitha Jessa, Juma Bhagat Ismail, Kamadia (Itmadi) Jiwan Laljee, Salehmohamed Walli Dharsee, Janmohamed Jetha, Kamadia Fazal Shivji.

By the end of the nineteenth century, when the interior of East Africa was becoming more accessible through the construction of roads and railways, an increasing number of trading establishments moved from Zanzibar to the East African mainland, resulting in large numbers of Nizari Ismailis moving inland. Living in various colonial constituencies, the Ismailis had to learn the language of the respective colonial powers, adapting their culture to new environments. With assistance from the Imam, Ismailis began to establish roots in Africa.

In 1918, Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah established the first Aga Khan Boys School in Mombasa, Kenya and in 1919, the first Aga Khan Girls School, also in Mombasa.

Ismailis, Zanzibar, East Africa

An advertisement poster produced circa 1930 Source: The Ismailis An Illustrated History

Having lost its importance as the main commercial centre of the region, Zanzibar ceased to be the seat of the East African Nizari Ismaili community.

AKDN has invested in development in Zanzibar since 1988. The Aga Khan Trust for Culture has been involved in restoration and revitalisation work in Zanzibar beginning in 1996.

Aga Khan trust for Culture

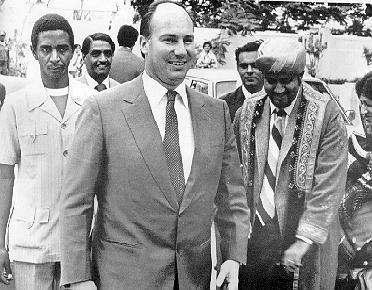

Mawlana Hazar Imam reviewing the restoration works on the seawall that fronts Zanzibar’s Forodhani Park with architects from the Aga Khan Trust for Culture. Photo: AKDN/Zahur Ramji

For more information, visit Zanzibar Stone Town Projects and AKDN in Tanzania.

Sources:

Farhad Daftar, Zulfikar Hirji, The Ismailis: An Illustrated History

Farhad Daftary, The Ismailis Their History and Doctrines, Cambridge University Press, 1998

Zanzibar, Encyclopedia Britannica

Photos at:

nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2019/08/22/early-ismaili-settlers-of-east-africa-established-a-foothold-in-zanzibar/?utm_source=Direct

Posted by Nimira Dewji

The archipelago of Zanzibar comprising two main islands (Unguja – commonly known as Zanzibar and Pemba) and several smaller ones, has been inhabited for over 20,000 years when the island served as a gateway for traders between the African Great Lakes, the Arabian Peninsula, the Indian subcontinent, and Europe.

In 1503, Zanzibar became part of the Portuguese Empire for almost 200 years. In 1698, Zanzibar came under the reign of the Sultanate of Oman, and subsequently under British rule in 1890. The island became independent in 1963, joining Tanganyika in the following year to form the Republic of Tanzania.

Zanzibar

Encyclopaedia Britannica

Several communities began to migrate to Zanzibar in the seventh century; the earliest immigrants were Africans followed by Arabs. The Persians, mostly from the city of Shiraz, began to arrive in the tenth century and, over time, became absorbed into the local population. The African-Persian population, who adopted many Persian traditions, came to be known as Shirazi.

Early Ismaili Settlers

The earliest Nizari Ismailis to immigrate to East Africa from the Indian subcontinent first established their foothold in Zanzibar in the 1800s although Ismaili merchants and other traders based in western India had been trading in western Indian Ocean since at least the seventeenth century. Traders used the northeast monsoon winds to travel across the Indian Ocean with their merchandise, often at sea for a month or longer in harsh conditions. When the monsoon winds changed direction to southwest, traders returned home with their wares.

The early Ismailis settlers in Zanzibar were farmers, who were compelled to immigrate due to successive droughts and famines that had caused economic hardships, also provoked by British industrialisation and economic policies. Eventually large numbers of community members of diverse backgrounds began to migrate. When Zanzibar became the Omani capital in 1832, it provided political stability and security as well as enhanced economic opportunities for traders to expand their businesses. India-based merchants became politically and economically important for the local rulers who appointed many of them to the post of chief customs inspectors, including Tharia Topan (d. 1891), Allidina Visram (d. 1916), and others.

Zanzibar Ismailis topan aga khan

Sultan Sayyed Bargash bin Said (d. 1888) seated, centre, with members of his court including Sir Tharia Topan (d. 1891) standing, centre. who served as the Sultan’s chief customs officer and was given the honorary title of Prime Minister of Zanzibar. Source: The Ismailis An Illustrated History

The first Nizari Ismaili jamatkhana in Zanzibar was established in the 1830s, with the appointments of mukhis and kamadias, during the time of the forty-sixth Imam Hasan Ali Shah Aga Khan I (1804-1881). The darkhana of Zanzibar was officially opened by Imam Sultan Muhammed Shah (1877-1957) on August 16, 1905.

jamatkhana zanzibar east africa

Zanzibar jamatkhana. Source: Khojawiki

Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah also issued the first Ismaili Constitution in 1905, in Gujarati, under the title Khoja Shia Imami Ismaili Counsilna Kayadani Book: Prakaran Pelu thata Biju (The Rule Book of the Khoja Shia Imami Ismaili Council: Parts 1 and 2). This document was instituted along with the first Supreme Council for Africa.

Ismaili Constitution

Front inside cover of the Ismaili Constitution issued at Zanzibar in 1905. Photo: The Ismailis An Illustrated History.

Sultan Muhammad Shah Aga Khan III Zanzibar

First Supreme Council for Africa. Photo: The Ismailis An Illustrated History left to right: Top, standing: Mohamed Bhanji, Gulamhusein Harji Sumar Muhamed Rashid Alana, Ali Valli Issa, Gulamhussein Karmali Bhaloo Middle, seated: Pirmohamed Kanji, Visram Harji, President Vizier Mohamed Rahemtulla Hemani, Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah al-Husayni Aga Khan III, Fazal Essani, Gulamhusien Bhaloo Kurji. Bottom row, seated: Mukhi Rajabali Gangji, Vizier Kassam Damani, Janmohamed Hansraj, Rai Mitha Jessa, Juma Bhagat Ismail, Kamadia (Itmadi) Jiwan Laljee, Salehmohamed Walli Dharsee, Janmohamed Jetha, Kamadia Fazal Shivji.

By the end of the nineteenth century, when the interior of East Africa was becoming more accessible through the construction of roads and railways, an increasing number of trading establishments moved from Zanzibar to the East African mainland, resulting in large numbers of Nizari Ismailis moving inland. Living in various colonial constituencies, the Ismailis had to learn the language of the respective colonial powers, adapting their culture to new environments. With assistance from the Imam, Ismailis began to establish roots in Africa.

In 1918, Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah established the first Aga Khan Boys School in Mombasa, Kenya and in 1919, the first Aga Khan Girls School, also in Mombasa.

Ismailis, Zanzibar, East Africa

An advertisement poster produced circa 1930 Source: The Ismailis An Illustrated History

Having lost its importance as the main commercial centre of the region, Zanzibar ceased to be the seat of the East African Nizari Ismaili community.

AKDN has invested in development in Zanzibar since 1988. The Aga Khan Trust for Culture has been involved in restoration and revitalisation work in Zanzibar beginning in 1996.

Aga Khan trust for Culture

Mawlana Hazar Imam reviewing the restoration works on the seawall that fronts Zanzibar’s Forodhani Park with architects from the Aga Khan Trust for Culture. Photo: AKDN/Zahur Ramji

For more information, visit Zanzibar Stone Town Projects and AKDN in Tanzania.

Sources:

Farhad Daftar, Zulfikar Hirji, The Ismailis: An Illustrated History

Farhad Daftary, The Ismailis Their History and Doctrines, Cambridge University Press, 1998

Zanzibar, Encyclopedia Britannica

Photos at:

nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2019/08/22/early-ismaili-settlers-of-east-africa-established-a-foothold-in-zanzibar/?utm_source=Direct

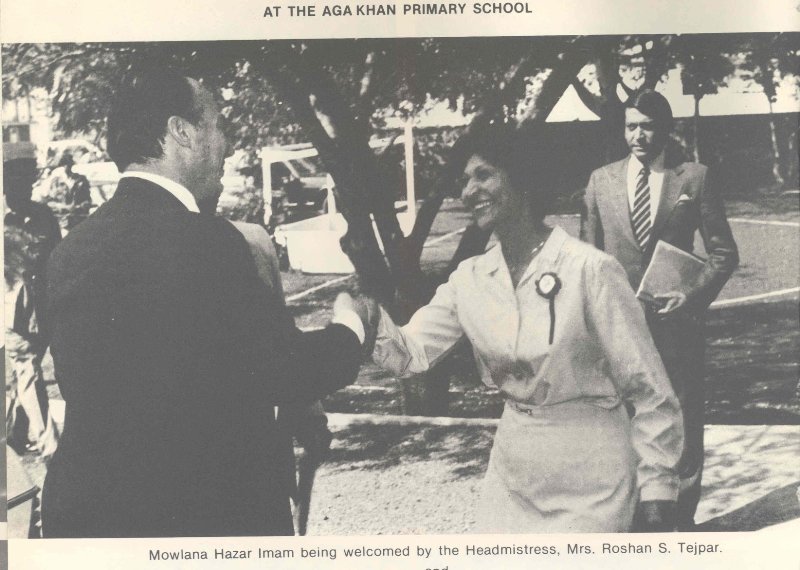

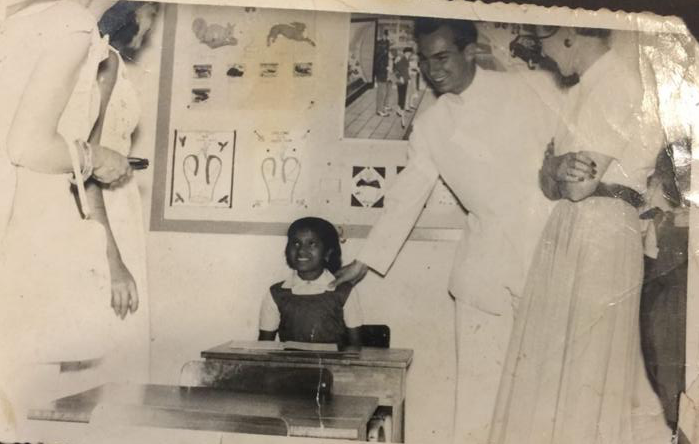

The establishment of schools by Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah began a period of stability

Posted by Nimira Dewji

The gradual migration of Ismailis from Zanzibar into the interiors of East African countries took place during the major political events of the region. “By 1914, the European powers had divided most of the African continent among themselves and installed colonial systems of government in their territories. The Ismailis were thus settled in what were effectively territories that belonged to, or were under the protection of Britain (Zanzibar, Kenya, Uganda, and the Union of South Africa), France (Madagascar), Germany (Tanganyika or German East Africa), and Portugal (Mozambique)” (The Ismailis An Illustrated History p 206).

“The socio-political scene changed again after World War I, when Germany ceased to be a major colonial power in East Africa, giving way to Britain and Belgium (which took the provinces of Ruanda and Urundi, later Rwanda and Burundi, areas where Ismailis were also to settle in later decades). As part of these different colonial constituencies, the Ismailis had to adapt to local conditions, for example, learning the languages of the respective colonial power, and adapting their cultures to new environments.

In the post-war period, the Ismailis in East Africa, with the assistance of the Imam, began to establish themselves more firmly, putting down roots in the African soil” (The Ismailis An Illustrated History p 209). The establishment of schools by Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah (1905 in Zanzibar; 1918-Boys’ School in Mombasa, Kenya; 1919-Girls’ School in Mombasa) marked the start of a period of stability and growth for the Ismailis. Although the migrant Ismailis shared a common religious heritage, they spoke different languages (Kutchi, Gujarati, Punjabi, Sindhi), had different cultures, and had varied occupations.

Ismailis, Zanzibar, East Africa

An advertisement poster produced circa 1930 Source: The Ismailis An Illustrated History

“By 1930, the British, either directly or indirectly, ruled over the greater part of the subcontinent and the adjacent territories, extending to the borders of Afghanistan, Nepal, and China” (The Ismailis An Illustrated History p 212). While there were large communities in the provinces of Gujarat and Kutch, the community “spread throughout the British areas from Rangoon, Burma (modern-day Myanmar) to the port of Gwadur (which was part of the Sultanate of Oman where the British had influence), and north into the Khyber mountain villages of Chitral, Gilgit, and Hunza valley (now in northern Pakistan). Some communities were concentrated in major towns and cities such as Bombay (Mumbai) and Poona (Pune) whereas others stayed in their villages, sometimes in very rural and isolated locations.

Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah developed organisational structures for all these different communities in the Indian subcontinent similar to those he had established for the Ismaili settlements in East Africa, emphasising education and civic duties

ismailis Karachi Aga Khan

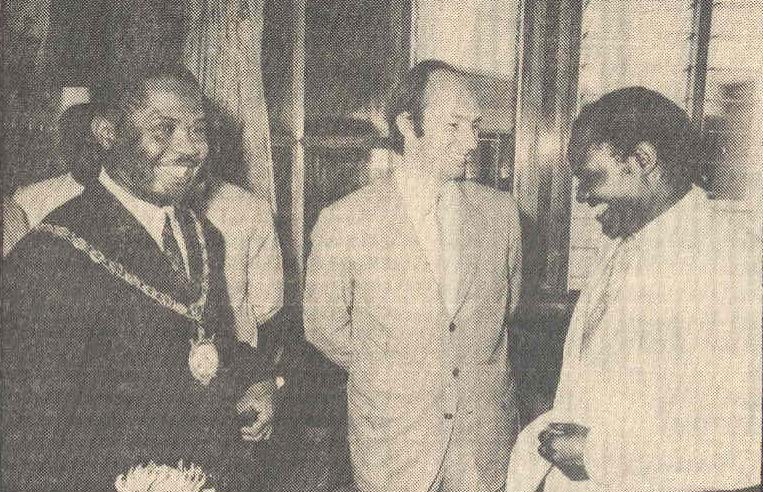

The Managing Committee of Khoja (Ismaili) Panjabhoy Club, Karachi 1938-1939. These clubs were known for their ethos of volunteer work and philanthropy inside and outside the Ismaili community. Source: The Ismailis An Illustrated History

In addition to a variety of occupations, Ismailis were also involved in literary activities including journalism and publishing. Their magazines, which included Ismaili Sitara and Bombay Ismaili, were written for the Ismaili community, but were widely circulated and read. These magazines were written in Gujarati, Sindhi, and English, and featured articles on various topics including wisdom literature, practical advice, health tips, and stories (The Ismailis An Illustrated History p 215).

Ismailis Aga Khan India

Inside cover of 1909 edition of Ismaili Sitara. Source: The Ismailis An Illustrated History

Ismailis Bombay India Aga Khan

A lantern advertisement from 1917 edition of “Bombay Ismaili.” Source: The Ismailis An Illustrated History

Ismailis Bombay Aga Khan

Advertisement for hats appearing in the “Bombay Ismaili.” Source: The Ismailis An Illustrated History

Source:

Farhad Daftary, Zulfikar Hirji, The Ismailis An Illustrated History, Azimuth Editions in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Images at:

nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2019/08/26/the-establishment-of-schools-by-imam-sultan-muhammad-shah-began-a-period-of-stability/

Posted by Nimira Dewji

The gradual migration of Ismailis from Zanzibar into the interiors of East African countries took place during the major political events of the region. “By 1914, the European powers had divided most of the African continent among themselves and installed colonial systems of government in their territories. The Ismailis were thus settled in what were effectively territories that belonged to, or were under the protection of Britain (Zanzibar, Kenya, Uganda, and the Union of South Africa), France (Madagascar), Germany (Tanganyika or German East Africa), and Portugal (Mozambique)” (The Ismailis An Illustrated History p 206).

“The socio-political scene changed again after World War I, when Germany ceased to be a major colonial power in East Africa, giving way to Britain and Belgium (which took the provinces of Ruanda and Urundi, later Rwanda and Burundi, areas where Ismailis were also to settle in later decades). As part of these different colonial constituencies, the Ismailis had to adapt to local conditions, for example, learning the languages of the respective colonial power, and adapting their cultures to new environments.

In the post-war period, the Ismailis in East Africa, with the assistance of the Imam, began to establish themselves more firmly, putting down roots in the African soil” (The Ismailis An Illustrated History p 209). The establishment of schools by Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah (1905 in Zanzibar; 1918-Boys’ School in Mombasa, Kenya; 1919-Girls’ School in Mombasa) marked the start of a period of stability and growth for the Ismailis. Although the migrant Ismailis shared a common religious heritage, they spoke different languages (Kutchi, Gujarati, Punjabi, Sindhi), had different cultures, and had varied occupations.

Ismailis, Zanzibar, East Africa

An advertisement poster produced circa 1930 Source: The Ismailis An Illustrated History

“By 1930, the British, either directly or indirectly, ruled over the greater part of the subcontinent and the adjacent territories, extending to the borders of Afghanistan, Nepal, and China” (The Ismailis An Illustrated History p 212). While there were large communities in the provinces of Gujarat and Kutch, the community “spread throughout the British areas from Rangoon, Burma (modern-day Myanmar) to the port of Gwadur (which was part of the Sultanate of Oman where the British had influence), and north into the Khyber mountain villages of Chitral, Gilgit, and Hunza valley (now in northern Pakistan). Some communities were concentrated in major towns and cities such as Bombay (Mumbai) and Poona (Pune) whereas others stayed in their villages, sometimes in very rural and isolated locations.

Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah developed organisational structures for all these different communities in the Indian subcontinent similar to those he had established for the Ismaili settlements in East Africa, emphasising education and civic duties

ismailis Karachi Aga Khan

The Managing Committee of Khoja (Ismaili) Panjabhoy Club, Karachi 1938-1939. These clubs were known for their ethos of volunteer work and philanthropy inside and outside the Ismaili community. Source: The Ismailis An Illustrated History

In addition to a variety of occupations, Ismailis were also involved in literary activities including journalism and publishing. Their magazines, which included Ismaili Sitara and Bombay Ismaili, were written for the Ismaili community, but were widely circulated and read. These magazines were written in Gujarati, Sindhi, and English, and featured articles on various topics including wisdom literature, practical advice, health tips, and stories (The Ismailis An Illustrated History p 215).

Ismailis Aga Khan India

Inside cover of 1909 edition of Ismaili Sitara. Source: The Ismailis An Illustrated History

Ismailis Bombay India Aga Khan

A lantern advertisement from 1917 edition of “Bombay Ismaili.” Source: The Ismailis An Illustrated History

Ismailis Bombay Aga Khan

Advertisement for hats appearing in the “Bombay Ismaili.” Source: The Ismailis An Illustrated History

Source:

Farhad Daftary, Zulfikar Hirji, The Ismailis An Illustrated History, Azimuth Editions in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Images at:

nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2019/08/26/the-establishment-of-schools-by-imam-sultan-muhammad-shah-began-a-period-of-stability/

The Quedagh Merchant

The story of a ship belonging to a wealthy Khoja merchant from Surat, which was pirated and for which the notorious English pirate, Capt. William Kidd has hanged 300 years ago..

Researching Khoja families' histories from East Africa, I came across a most intriguing item.

Back in the 1960s, Rai Shamshudin Tejpar, a Dar-es-Salaam Khoja Ismaili missionary (preacher) had once intimated to his audience that somewhere in history, a Khoja-owned ship had been captured by a notorious English pirate. Although this was quite probable as it is well-known that Khoja merchants were active in the Indian Ocean littoral trading area from as early as 16th century and were frequently mentioned in Portuguese official documentation of the mid-1500 (See Khoja Shams-ud-din Gillani, a business associate of the Portuguese governors of Goa) - the piracy connection was something I had never heard of.

Then, in March 2017, Shirin Walji, an Ismaili Studies scholar from Edmonton donated her collection of East African materials to Khojawiki and included in there was a clipping from 1936 in a Zanzibari newspaper called in “Samachar” and sure enough, it provided the following titbit:

“According to Major F.B. Pearce, one of the prizes taken by Captain Kidd the famous pirate, who roved the Indian Ocean at the close of the seventeenth century, was a ship belonging to a Cambay Khoja merchant.” (1)

Cambay (or present-day Khambhat) was a major sea-port located just up the waters from another old trading port, Surat and near modern-day Bhavnagar in Gujarat.

Major F B. Pearce was the British Resident (colonial administrator) of Zanzibar and published a detailed account of Zanzibar and its inhabitants published in 1920, wherein he talks about the Khojas as being the largest Indian group in Zanzibar and made the above assertion about Capt. Kidd (2)

More...

http://khojawiki.org/The_Quedagh_Merchant

The story of a ship belonging to a wealthy Khoja merchant from Surat, which was pirated and for which the notorious English pirate, Capt. William Kidd has hanged 300 years ago..

Researching Khoja families' histories from East Africa, I came across a most intriguing item.

Back in the 1960s, Rai Shamshudin Tejpar, a Dar-es-Salaam Khoja Ismaili missionary (preacher) had once intimated to his audience that somewhere in history, a Khoja-owned ship had been captured by a notorious English pirate. Although this was quite probable as it is well-known that Khoja merchants were active in the Indian Ocean littoral trading area from as early as 16th century and were frequently mentioned in Portuguese official documentation of the mid-1500 (See Khoja Shams-ud-din Gillani, a business associate of the Portuguese governors of Goa) - the piracy connection was something I had never heard of.

Then, in March 2017, Shirin Walji, an Ismaili Studies scholar from Edmonton donated her collection of East African materials to Khojawiki and included in there was a clipping from 1936 in a Zanzibari newspaper called in “Samachar” and sure enough, it provided the following titbit:

“According to Major F.B. Pearce, one of the prizes taken by Captain Kidd the famous pirate, who roved the Indian Ocean at the close of the seventeenth century, was a ship belonging to a Cambay Khoja merchant.” (1)

Cambay (or present-day Khambhat) was a major sea-port located just up the waters from another old trading port, Surat and near modern-day Bhavnagar in Gujarat.

Major F B. Pearce was the British Resident (colonial administrator) of Zanzibar and published a detailed account of Zanzibar and its inhabitants published in 1920, wherein he talks about the Khojas as being the largest Indian group in Zanzibar and made the above assertion about Capt. Kidd (2)

More...

http://khojawiki.org/The_Quedagh_Merchant

KHOJAS IN EARLY BOMBAY:

by I.I.Dewji, Editor, www.khojawiki.org (2019)

In a great many ways, the outstanding success of the present-day Khoja global diaspora is an outcome of their 19th-century migration from Surat-Kutch-Kathiawar to this fast-growing English colonial port-city, located just south of Gujarat, on India’s western seaboard and within the ancient Indian Ocean trading networks.

By 1534, Khoja merchants from Gujarat were trading with the Portuguese (see Khoja Shams-ud-din Gillani) and so when the Sultan of Gujarat seceded “Bom Bahia,” “the beautiful bay” to the Portuguese, it is likely that the Khojas would have started trading from there. They would have been amongst its leading merchants in 1661 when Bombay was handed over as “dowry” to the English. (Read here the story of Khoja merchant Kurji and his ship The Quedagh Merchant that was captured by the notorious English pirate, Capt Kidd in 1698.) (1)

By 1668, the more established Khoja merchants from Surat were lured by the English East India Company when it transferred its base to Bombay to take advantage of the growing business opportunities as they expanded their hold in India.

“The arrival of many Indian and British merchants led to the development of Bombay's trade by the end of the seventeenth century. Soon it was trading in salt, rice, ivory, cloth, lead, and sword blades with many Indian ports as well as with the Arabian cities of Mecca and Basra” (2)

However, it was Skull Famine of 1791 (see Gujarat Famines & Khoja Migrations) which decimated almost 11 million people in North India, which forced many poorer Khojas to move to the relative safety of Bombay, assisted by the charity of the wealthier caste members. By this time, Bombay’s total population was about 100,000. (3)

Within the community, there is an oral tradition that the Khojas Jamaat owned a graveyard since 1790 in Dongri, the Khoja mohalla neighborhood. (see Alarakhia Sumar)

That the Khojas were definitely living in Bombay by the end of the 1700s was also confirmed by the Ismaili Imam’s lawyer in the Agakhan Case of 1866 (4)

However, the earliest written record of the Khoja presence is from 1804 when the Khojas mortgaged their jamaat-khana building to a shroff (money-lender ed.) for the sum of Rs.17,000, to send to their Imam in Iran. (5)

Also later when the Bombay Khoja Jamaat account books were seized by the British courts in ongoing litigation, records show that Rs.1,300 was sent to the Ismaili Imam Shah Khalil Allah in 1807 (6).

The Bombay Khoja Jamat Book also clearly notes their presence in Bombay after 1806-1807. (7) During this period, the Khojas organized themselves in a setup that they had also used in India for centuries.

“The structure of administration remained much the same as had been introduced by Pir Sadr al-Din. It consisted of a federation of cells, each with a single jamaat or community, at its base. Each council was composed of all the adult males in each jamaat with decisions regarding community affairs made in meetings at the council-hall, the jamaat-khana. For each jamaat-khana, there was a treasurer or steward, the Mukhi, and the accountant, the Kamadia.” (8)

Later, during the course of the 19th and 20th centuries, Bombay became an active litigious society and since the Khoja merchants were fiercely protective of their property inheritance rights, we have some well-documented information on their lives.

In one such inheritance case, witness testimony by one Hassoon Syed stated that of the 150 to 200 Khoja families in Bombay in the early 1820's, the majority lived quite modestly. (9)

Another series of famines in Kutch-Kathiawar in 1803, 1813-1814, 1823-1824, 1834-1835 caused further migrations to the safety of Bombay. (10) Oral tradition has it that almost 1500 Khojas moved from the Junagadh area to Bombay during this period. Alarakhia Sumar, a prominent Mukhi of the Khoja Jamaat, was credited with their settlement in Bombay at this time.

Cassum Natha, another court witness, estimated, that by 1847, the Khoja community was closer to 600 families, with approximately 1,000 or 1,500 persons. (11)

In this migration, family connections, caste networks and a reputation of honesty made it possible for the Khojas to prosper rapidly. For example, frequently in business, if one failed or defaulted, others would rally around to discharge his debts so as to keep their caste business reputation intact. (12)

"Bombay’s Mohammed All Road in Dongri (13) became a major centre of Ismaili Khoja settlement, with Khoja families migrating from Kutch and Kathiawar in Gujarat to establish business ventures that derived from an existing Gujarati, mercantile culture". (14)

By this time, the Khojas became so established in the Bombay rice distribution that the term "Khoja" also came to describe brokers of parched rice. (15)

"....by 1841, there were some 2,000 Khojas there, mostly small traders in grains with a few large merchants." (16)

Justice Perry, in his 1847 judgment in Hirbae v. Sonabae. Gungbae Sonabae, also a significant Inheritance dispute, estimated the number of Khojas in Bombay to be 2,000. (17)

Whilst these early communities thrived in the new prosperity of Bombay, they had their share of disagreements, as the records show that the earliest riots in Bombay’s history occurred at Mahim in 1850 in consequence of a dispute between two rival factions of the Khojas. (18)

By 1866, their numbers in Bombay had grown to about 4,000. (19)

Gradually, the Khojas began to use Bombay as their base to pursue trade opportunities, primarily in Africa, but also in other parts of Asia. (20) (see U Kan Gyi) Rajabali Jumabhoy Dewji Jamal

"By 1860, the Bombay Khojas went into the opium trade in a big way and by 1890, they had overtaken the Parsis from this most lucrative trade". (21)

Whilst the general success of Gujarati immigrants is well documented and attributed to their centuries-old marine mercantile culture, the Khojas had some advantages over other Muslims due to their syncretic faith system.

"These Ismaili communities (Khojas and Bohoras) often followed social practices and customary laws which bore close relation to the Hindu communities from which they had converted. … More crucially, local usages regarding usury and inheritance laws allowed them to accumulate and retain capital within the family beyond the constraints, which orthodox Islamic law may have imposed." (22)

Clearly, though, it was through these methods of wealth generation and transmission that the Khojas had raised themselves from obscurity, poverty, and illiteracy to prominence, wealth and intelligence during the 19th century. (23)(Sir Currimbhoy Ebrahim, Baronet (Baronetcy) Muhammad Ali Jinnah (Barrister & Politician),Rahimtullah Muhammad Sayani Jaffer Rahimtoola , Abdulla Dharamsi (Lawyers), Jaffer Padamsee (Landlord) Ibrahim Rahimtoola, Sir Rahimtoola M. Chinoy; Mohamed Ibrahim Rawjee (Civic Leaders).

Some historians have argued that the Khoja Inheritance cases arose largely from the fears of a mercantile community to the dissipation of family wealth, which may have actually happened as the Khojas of Bombay (and Zanzibar) seemed to have lost their economic clout by early 20th century.

"By the end of the nineteenth century, the Bombay community numbered around 8,500 and was vibrant, relatively wealthy, with several members engaged in a wide range of economic activity" (24) (see Manji Ghulamhussian Padamsee (Glassware), Laljibhai Devraj (Glassware), Ahmed Devji (Furniture) Dewji Jamal (Shipping).

They also began to spread themselves across the Bombay area. In the 1881 census, Khojas were noted as residents of the suburb of Bandra. (25)

Whilst most Khojas were small traders and shopkeepers, a number of major family fortunes were made during the second half of the century and they ended being amongst the global elites in wealth, education, travel and sophistication.

For instance, the first school in Khoja history was established in Bombay around 1825, whilst an English medium school was set-up and run by the Khojas, through the generosity of Kassambhai Nathabhai by 1850’s. (26)

As early as the 1850’s, a private newspaper called “The Khoja Doost” was launched in Bombay.

Some of these families were engaged in the incredible Bombay cotton mills industry, which came into being around the 1860s, largely in response to the growing trade with East Africa through the port of Zanzibar, where the Khojas and other Kutchi-Kathiawari merchants had established successful distribution networks. (see 200 Years of History of Khojas in Zanzibar)

"Since the 1860s the Bombay economy has been based on cotton - its export and the manufacture of cloth. With the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 and the consequent cotton famine, Bombay suddenly emerged with a virtual monopoly of the world cotton trade. Its merchants acquired wealth, land and prosperity surpassing that possessed by the colonial masters." (27) (See Sir Currimbhoy Ebrahim), Dostmohamed Allana)

"Bombay had become the Indian Ocean’s most important commercial and industrial center and its success was related, in part, to East African demand for a constellation of consumer goods" (28) (see Sir Tharia Topan of Zanzibar - who even opened an office in Bombay)

Another very bad famine, the “Chappanyo” of 1899-1901 (see Gujarat Famines & Khoja Migrations) caused more to flee from Kathiawar and according to the 1901 Census, the total Khoja population in Western India was estimated at 50.837 (25.555 males and 25.282 females) and by 1911 Census, 52,367 (26,387 males and 25,980 females) (29).

As was custom for centuries, the Khoja caste connections established charitable initiatives to deal with these catastrophes. (Tharia Topan’s & Allidina Visram made frequent visits to India to persuade Khojas to move to Africa and to recruit migrants for their enterprises.)

In the steam age following the 1870s, Bombay became a major embarkation port for those headed for better lives in East Africa, as there now was a regular service between Bombay and Zanzibar and later after the establishment of direct British colonial rule in East Africa, to Mombasa. (see Hasham Jamal Pradhan) Saboor Chatoor

"Within one month, he (the Protector of Emigrants in Bombay) counted 1,449 people leaving for East African ports. The total for the year 1895-96, of 6,908, was more than twice the number of the preceding year. The passengers onboard one of these ships, questioned by the Protector, included, among others, thirty-two masons and tile turners from Kutch, sixty laborers from villages in Gujarat, three Khojas and four Hindu tailors from Rajkot, and sixteen Brahmins, who intended to “follow whatever suitable business offers." (30)