SHAHNAMA

I am pretty sure there are lots of versions in English. Here are two different translations in English:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Shahnameh-Persi ... 793&sr=8-1

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Shahnameh-Persi ... 832&sr=1-2

If you search "Shahnahmeh" in Amazon:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/s/ref=nb_ss?url ... eh&x=0&y=0

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Shahnameh-Persi ... 793&sr=8-1

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Shahnameh-Persi ... 832&sr=1-2

If you search "Shahnahmeh" in Amazon:

http://www.amazon.co.uk/s/ref=nb_ss?url ... eh&x=0&y=0

Today in history: Firdawsi’s Shahnama, was completed

Posted by Nimira Dewji

Abu’l-Qasim Firdawsi (940-1020) completed his epic work, the Shahnama (Book of Kings), on February 25, 1010.1 Fearful that Persia’s history would be forgotten, Firdawsi set about composing a poem that integrated existing written accounts and orally transmitted tales. Partly legend, partly historic, the Shahnama comprises more than 60,000 rhyming couplets, telling the story of Persia from the time of creation to its conquest by Muslims in the seventh century.

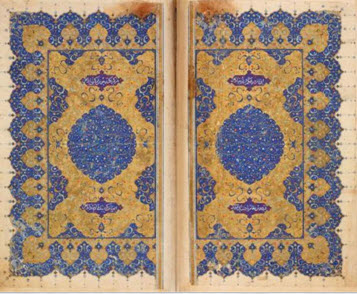

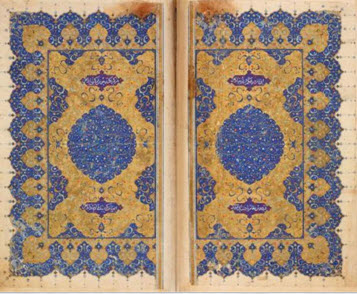

Shahnama Firdawsi Firdausi

The Shahnama of Firdawsi, Iran, Shiraz, 1539. Dallas Museum of Art.

The first part tells of the mythical creation of Persia and its earliest mythical past; the second part tells of the legendary kings and heroes; the third part blends historical fact with legend, telling of the semi-mythical adventures of actual historical kings.

The Shahnama is organised according to the reigns of fifty kings (shahs). “Valued in its time as a work of history and for its ethical content (as a mirror for princes), the major themes of the Shahnama include the full range of human traits evidenced by rulers, their wise and foolish actions, the inevitability of human destiny, and the endemic jealousy of peoples living beyond Iran’s borders. Stories about each king’s life and rule, of the challenges they confront, alternate with those of heroes, such as Rustam, who dedicate their service to the kings. The kings’ reigns are assigned by God (Yazdan); so long as God’s appointed king rules Iran, in theory at least, Iran’s security and prosperity will be preserved” (Treasures of the Aga Khan Museum, p 204).

Shahnama shahname firdawsi firdousi aga khan museum

Shah Kay Kavus attempts to fly to heaven. Folio from Shahnama, Shiraz, Iran, 1341. King Kay Kavus was tempted by a demon to fly to heaven and conquer the secrets of the celestial spheres. The king ordered his servants to collect live eagle chicks, and hand-rear them in the palace on fresh meat. Once fully grown, Kavus ordered his servants to harness four of the birds to a specially-constructed throne, with slabs of raw meat suspended just above the eagles. The king then sat in his contraption, and the eagles soon had him airborne, as they struggled to reach the dangling food, depicted here. Kavus points up in excitement towards the approaching the stars. Eventually the birds grew tired, and the king’s upward trajectory came to an end, tipping out the royal passenger in a remote region. He survived the failed adventure, but was greatly humiliated by his noblemen when they came to rescue him. Source: Treasures of the Aga Khan Museum Catalogue p. 206

Firdawsi began to compose his epic shortly after 975, at a time when eastern Iran came under Samanid reign (900-1005), ushering in one of the most brilliant periods in the cultural history of Persia. At their court in Bukhara, in present-day Uzbekistan, the Samanids supplemented Arabic with Persian language, the lingua france of the ruling elite of western Asia and northern India, initiating a Persian renaissance. By the time Firdausi completed the Shahnama, the Samanids had been overthrown by the Ghaznavids (r. 977-1186), ending the brief Persian renaissance.

The Shahnama, which set the standard for the Persian language, influenced several works of art produced in greater Iran as well as the eastern Islamic regions. Specific stories and characters were used as motifs to decorate ceramics, tile panels, inlaid metalwork, lacquer work, and textiles. Many rulers patronised lavishly illustrated copies of the Shahnama, and today their pages can be found in museums and private art collections around the world.

Shahnama Firdausi Peria

Beaker, 12th century Iran, illustrating a narrative from the Shahnama. Organised in horizontal bands, the small, highly detailed images recount the adventures of Bizhan and Manizha. The climax in the narrative appears in the lower register and depicts Rustam rescuing Bizhan from the pit where he has been imprisoned by the Turanian king Afrasiyab, Manizha’s evil father. Source: FreerISackler, The Smithsonian’s Museums of Asian Art

Shahnama persia faridun zahhak

Copper alloy bowl engraved and overlaid in silver and gold, Iran, 1351-1352. Depicting from the Shahnama, the legendary King Faridun riding an ox followed by a captive on foot. The captive is the evil King Zahhak, whom Faridoun overthrew. Source: Victoria & Albert Museum.

The Shahnama was copied in all the Iranian royal studios for rulers across the Persian-speaking world including the Mughal empire. Over time, it achieved unrivalled status and is considered the most impressive expression of Persian literary and national identity.

Sources:

Treasures of the Aga Khan Museum, Masterpieces of Islamic Art, Aga Khan Trust for Culture

The Shahname, The British Library

Mario Casari, Firdausi’s Shahnama and the discovery of Persian in early modern Europe, Zoroastrian Heritage

K. E. Eduljee, Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, Zoroastrian Heritage

nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2019/02/25/feb-25today-in-history-firdawsis-shahnama-was-completed/

Posted by Nimira Dewji

Abu’l-Qasim Firdawsi (940-1020) completed his epic work, the Shahnama (Book of Kings), on February 25, 1010.1 Fearful that Persia’s history would be forgotten, Firdawsi set about composing a poem that integrated existing written accounts and orally transmitted tales. Partly legend, partly historic, the Shahnama comprises more than 60,000 rhyming couplets, telling the story of Persia from the time of creation to its conquest by Muslims in the seventh century.

Shahnama Firdawsi Firdausi

The Shahnama of Firdawsi, Iran, Shiraz, 1539. Dallas Museum of Art.

The first part tells of the mythical creation of Persia and its earliest mythical past; the second part tells of the legendary kings and heroes; the third part blends historical fact with legend, telling of the semi-mythical adventures of actual historical kings.

The Shahnama is organised according to the reigns of fifty kings (shahs). “Valued in its time as a work of history and for its ethical content (as a mirror for princes), the major themes of the Shahnama include the full range of human traits evidenced by rulers, their wise and foolish actions, the inevitability of human destiny, and the endemic jealousy of peoples living beyond Iran’s borders. Stories about each king’s life and rule, of the challenges they confront, alternate with those of heroes, such as Rustam, who dedicate their service to the kings. The kings’ reigns are assigned by God (Yazdan); so long as God’s appointed king rules Iran, in theory at least, Iran’s security and prosperity will be preserved” (Treasures of the Aga Khan Museum, p 204).

Shahnama shahname firdawsi firdousi aga khan museum

Shah Kay Kavus attempts to fly to heaven. Folio from Shahnama, Shiraz, Iran, 1341. King Kay Kavus was tempted by a demon to fly to heaven and conquer the secrets of the celestial spheres. The king ordered his servants to collect live eagle chicks, and hand-rear them in the palace on fresh meat. Once fully grown, Kavus ordered his servants to harness four of the birds to a specially-constructed throne, with slabs of raw meat suspended just above the eagles. The king then sat in his contraption, and the eagles soon had him airborne, as they struggled to reach the dangling food, depicted here. Kavus points up in excitement towards the approaching the stars. Eventually the birds grew tired, and the king’s upward trajectory came to an end, tipping out the royal passenger in a remote region. He survived the failed adventure, but was greatly humiliated by his noblemen when they came to rescue him. Source: Treasures of the Aga Khan Museum Catalogue p. 206

Firdawsi began to compose his epic shortly after 975, at a time when eastern Iran came under Samanid reign (900-1005), ushering in one of the most brilliant periods in the cultural history of Persia. At their court in Bukhara, in present-day Uzbekistan, the Samanids supplemented Arabic with Persian language, the lingua france of the ruling elite of western Asia and northern India, initiating a Persian renaissance. By the time Firdausi completed the Shahnama, the Samanids had been overthrown by the Ghaznavids (r. 977-1186), ending the brief Persian renaissance.

The Shahnama, which set the standard for the Persian language, influenced several works of art produced in greater Iran as well as the eastern Islamic regions. Specific stories and characters were used as motifs to decorate ceramics, tile panels, inlaid metalwork, lacquer work, and textiles. Many rulers patronised lavishly illustrated copies of the Shahnama, and today their pages can be found in museums and private art collections around the world.

Shahnama Firdausi Peria

Beaker, 12th century Iran, illustrating a narrative from the Shahnama. Organised in horizontal bands, the small, highly detailed images recount the adventures of Bizhan and Manizha. The climax in the narrative appears in the lower register and depicts Rustam rescuing Bizhan from the pit where he has been imprisoned by the Turanian king Afrasiyab, Manizha’s evil father. Source: FreerISackler, The Smithsonian’s Museums of Asian Art

Shahnama persia faridun zahhak

Copper alloy bowl engraved and overlaid in silver and gold, Iran, 1351-1352. Depicting from the Shahnama, the legendary King Faridun riding an ox followed by a captive on foot. The captive is the evil King Zahhak, whom Faridoun overthrew. Source: Victoria & Albert Museum.

The Shahnama was copied in all the Iranian royal studios for rulers across the Persian-speaking world including the Mughal empire. Over time, it achieved unrivalled status and is considered the most impressive expression of Persian literary and national identity.

Sources:

Treasures of the Aga Khan Museum, Masterpieces of Islamic Art, Aga Khan Trust for Culture

The Shahname, The British Library

Mario Casari, Firdausi’s Shahnama and the discovery of Persian in early modern Europe, Zoroastrian Heritage

K. E. Eduljee, Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, Zoroastrian Heritage

nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2019/02/25/feb-25today-in-history-firdawsis-shahnama-was-completed/

-

swamidada_1

- Posts: 239

- Joined: Sun Nov 18, 2018 9:21 pm

AN INTERESTING ANECDOTE ABOUT SHAH NAMA:

Abul Qasim Firdousi was a famous poet of his time and was related to DARBAR of Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni (in modern day Afghanistan). Sultan Mahmud asked Firdousi to write a poetical account of kings of Persia (Iran) and offered one golden Ashrafi i.e a golden coin for each of couplet. Firdousi completed that history of kings in few volumes with 60,000 couplets. There were some influential persons attached with Darbar of Sultan who were biased and against Firdousi. They told Sultan Mahmud that Firdousi is Shia and belong to Ismaili sect. Mahmud was against Ismailis and on his way to SOMNATH in Gujrat, in Multan his armies massacred more than 100,000 Ismailis on his order. this account is mentioned in the book FATEH NAMA. Sultan Mahmud offered Firdousi 60,000 silver coins instead of golden coins. Firdousi refused to accept and reminded him of his promise. Later on Firdousi added few couplets of HAJJU at the end Shah Nama. In modern day publications these HAJJU couplets are not included. In Persian, Arabic, or urdu poetry HAJJU is a term which is used as sarcasm, satire, to ridicule the person, or any bad account for the person targeted.

Abul Qasim Firdousi was a famous poet of his time and was related to DARBAR of Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni (in modern day Afghanistan). Sultan Mahmud asked Firdousi to write a poetical account of kings of Persia (Iran) and offered one golden Ashrafi i.e a golden coin for each of couplet. Firdousi completed that history of kings in few volumes with 60,000 couplets. There were some influential persons attached with Darbar of Sultan who were biased and against Firdousi. They told Sultan Mahmud that Firdousi is Shia and belong to Ismaili sect. Mahmud was against Ismailis and on his way to SOMNATH in Gujrat, in Multan his armies massacred more than 100,000 Ismailis on his order. this account is mentioned in the book FATEH NAMA. Sultan Mahmud offered Firdousi 60,000 silver coins instead of golden coins. Firdousi refused to accept and reminded him of his promise. Later on Firdousi added few couplets of HAJJU at the end Shah Nama. In modern day publications these HAJJU couplets are not included. In Persian, Arabic, or urdu poetry HAJJU is a term which is used as sarcasm, satire, to ridicule the person, or any bad account for the person targeted.

Court of Kayumars, from Firdawsi’s Shahnama, depicts cosmic order

Fearful that Persia’s history would be forgotten, Abu’l-Qasim Firdawsi (940-1020) composed the Shahnama (Book of Kings), comprising more than 60,000 rhyming couplets, telling the story of Persia (modern-day Iran) from the time of creation to its conquest by Muslims in the seventh century. Partly legend, partly historic, it is also a manual on kingship, a collection of heroic tales, and a long essay on wisdom, love, warfare, and magic, structured around four successive dynasties, each representing the various phases of human history, seen from the Persian perspective.

The Shahnama of Firdawsi, Iran, Shiraz, 1539. Dallas Museum of Art.

In addition to being a great work of literature, the poem was a “mirror for princes,” a popular genre in medieval Islamic regions for the education of rulers. The models of conduct and teachings offered by the virtuous kings and heroes of the Shahnama explain its success throughout history.

The first part tells of the mythical creation of Persia and its earliest mythical past, beginning with the story of Kayumars (also spelled Kayomers), who was believed to be the world’s first human and the first legendary king (shah) of ancient Iran.

The name ‘Kayumars’ is the Persian form of Gayomard or Gayomart from the tradition of the Zoroastrian, one of the oldest monotheistic religions, founded by Prophet Zoroaster approximately 3,500 years ago. In Zoroastrian mythology, Kayumars had been granted supernatural powers by God, therefore, all animals and humans paid homage to him. During his thirty-year reign, Kayumars taught humans how to prepare food, introduced law and justice, and maintained harmony between animals and humans. The tranquillity was shattered when evil entered the world and the Black Demon killed Kayumars’s son Siyamak. In turn, Siyamak ’s son Hushang avenged the death of his father shortly before the death of Kayumars.

The second part of the Shahnama tells of the legendary kings and heroes; the third part blends historical fact with legend, telling of the semi-mythical adventures of actual historical kings.

The epic has been copied countless times. Comprising 759 text folios and 258 elaborate illustrations, the Shahnama made for Shah Tahmasp (r. 1524–76), the second shah of the Safavid dynasty (r. 1501-1732), represents the peak of sixteenth-century Persian art.

The Court of Gayumars from the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp attributed to Safavid master Sultan Muhammad, Iran, ca. 1524-25. Source: Aga Khan Museum

In the illustration titled Court of Kayumars, considered “a painting that humbles all artists,”1 Gayumars is seated before his community, all clad in leopard furs and skins, his son Siyamak seated to his left, and grandson Hushang standing to his right, implying the succession between father and son, although this never takes place due to the tragedy of the story.

The courtiers “stand in a circle, because the circle is the symbol of the sky in Persian thinking, and the sky in turn symbolises the universe. The courtiers standing in a circle send two messages. One is that Emperor Keyomars is the king of the universe, a standard eulogy, and the other is that the courtiers represent the emperor’s celestial court… The does shown reclining next to the peaceful felines transcribe a traditional literary image celebrating the just rule of the king that leads to universal harmony and safety for all” (Melikian-Chirvani, Pattern and Light p 51).

Lakhani notes that the King “is the prototype of the imago Dei or al-insan al-kamil (‘Perfect Man’). He represents the spiritually centred ruler who is the khalifa or [representative] of God on earth” (Faith and Ethics p xv).

The green grass represents spring in Persian poetry. The sky is painted gold “because gold is the colour of the sun, and therefore, of the light of glory shining upon the monarch. This signifies that the rule of Keyomars, sung as the first king of Iran in the Book of Kings, is the spring of Iranian kingship” (Melikian-Chirvani, Pattern and Light p 51).

The Court scene “descends from the celestial to the terrestrial, from the King to the Commons, reflecting the traditional devolution of order from the…kingdom of spiritual governance, symbolising the Spirit and its faculty of higher intellect, to the … kingdom of human governance, symbolising the soul and its faculty of the psyche, and thence to the subjects to be governed, symbolising the lower self and its appetites” (Lakhani, Faith and Ethics p xv).

Sources:

1 Treasures of the Aga Khan Museum, Masterpieces of Islamic Art p 216

Excerpt: Shahnameh, The Book of Kings, npr books

Assadullah Souren Melikian-Chirvani, “Discovering Art in the World of Islam,” Pattern and Light Aga Khan Museum, Skira Rizzoli Publications, 2014

https://nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2019/ ... rce=Direct

Fearful that Persia’s history would be forgotten, Abu’l-Qasim Firdawsi (940-1020) composed the Shahnama (Book of Kings), comprising more than 60,000 rhyming couplets, telling the story of Persia (modern-day Iran) from the time of creation to its conquest by Muslims in the seventh century. Partly legend, partly historic, it is also a manual on kingship, a collection of heroic tales, and a long essay on wisdom, love, warfare, and magic, structured around four successive dynasties, each representing the various phases of human history, seen from the Persian perspective.

The Shahnama of Firdawsi, Iran, Shiraz, 1539. Dallas Museum of Art.

In addition to being a great work of literature, the poem was a “mirror for princes,” a popular genre in medieval Islamic regions for the education of rulers. The models of conduct and teachings offered by the virtuous kings and heroes of the Shahnama explain its success throughout history.

The first part tells of the mythical creation of Persia and its earliest mythical past, beginning with the story of Kayumars (also spelled Kayomers), who was believed to be the world’s first human and the first legendary king (shah) of ancient Iran.

The name ‘Kayumars’ is the Persian form of Gayomard or Gayomart from the tradition of the Zoroastrian, one of the oldest monotheistic religions, founded by Prophet Zoroaster approximately 3,500 years ago. In Zoroastrian mythology, Kayumars had been granted supernatural powers by God, therefore, all animals and humans paid homage to him. During his thirty-year reign, Kayumars taught humans how to prepare food, introduced law and justice, and maintained harmony between animals and humans. The tranquillity was shattered when evil entered the world and the Black Demon killed Kayumars’s son Siyamak. In turn, Siyamak ’s son Hushang avenged the death of his father shortly before the death of Kayumars.

The second part of the Shahnama tells of the legendary kings and heroes; the third part blends historical fact with legend, telling of the semi-mythical adventures of actual historical kings.

The epic has been copied countless times. Comprising 759 text folios and 258 elaborate illustrations, the Shahnama made for Shah Tahmasp (r. 1524–76), the second shah of the Safavid dynasty (r. 1501-1732), represents the peak of sixteenth-century Persian art.

The Court of Gayumars from the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp attributed to Safavid master Sultan Muhammad, Iran, ca. 1524-25. Source: Aga Khan Museum

In the illustration titled Court of Kayumars, considered “a painting that humbles all artists,”1 Gayumars is seated before his community, all clad in leopard furs and skins, his son Siyamak seated to his left, and grandson Hushang standing to his right, implying the succession between father and son, although this never takes place due to the tragedy of the story.

The courtiers “stand in a circle, because the circle is the symbol of the sky in Persian thinking, and the sky in turn symbolises the universe. The courtiers standing in a circle send two messages. One is that Emperor Keyomars is the king of the universe, a standard eulogy, and the other is that the courtiers represent the emperor’s celestial court… The does shown reclining next to the peaceful felines transcribe a traditional literary image celebrating the just rule of the king that leads to universal harmony and safety for all” (Melikian-Chirvani, Pattern and Light p 51).

Lakhani notes that the King “is the prototype of the imago Dei or al-insan al-kamil (‘Perfect Man’). He represents the spiritually centred ruler who is the khalifa or [representative] of God on earth” (Faith and Ethics p xv).

The green grass represents spring in Persian poetry. The sky is painted gold “because gold is the colour of the sun, and therefore, of the light of glory shining upon the monarch. This signifies that the rule of Keyomars, sung as the first king of Iran in the Book of Kings, is the spring of Iranian kingship” (Melikian-Chirvani, Pattern and Light p 51).

The Court scene “descends from the celestial to the terrestrial, from the King to the Commons, reflecting the traditional devolution of order from the…kingdom of spiritual governance, symbolising the Spirit and its faculty of higher intellect, to the … kingdom of human governance, symbolising the soul and its faculty of the psyche, and thence to the subjects to be governed, symbolising the lower self and its appetites” (Lakhani, Faith and Ethics p xv).

Sources:

1 Treasures of the Aga Khan Museum, Masterpieces of Islamic Art p 216

Excerpt: Shahnameh, The Book of Kings, npr books

Assadullah Souren Melikian-Chirvani, “Discovering Art in the World of Islam,” Pattern and Light Aga Khan Museum, Skira Rizzoli Publications, 2014

https://nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2019/ ... rce=Direct