Islamic Art

Islamic Art

The Louvre’s New Islamic Galleries Bring Riches to Light

There is also a multimedia slide show linked at:

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/20/arts/ ... h_20120920

There is also a multimedia slide show linked at:

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/20/arts/ ... h_20120920

Dallas Museum of Art Joins New Worldwide Push for Islamic Art

by Kyle Chayka on November 1, 2012

http://hyperallergic.com/59551/dallas-m ... lamic-art/

Excerpt:

Islamic art seems to be going through an international moment in the spotlight as major museums reinvigorate their collection holdings and exhibition programming of art from the Middle East. The historically conservative Louvre museum opened an entire new wing devoted to Islamic art in September of this year, though its non-traditional, non-chronological installation has been critiqued as a “visual blur and intellectual confusion” by the New York Times and a “failure to acknowlege the modern Muslim condition” by the New Statesman. The Metropolitan Museum likewise renovated its Islamic galleries in 2011 with a presentation that has been better received.

Perhaps the biggest gesture of support for the western museum-ification of Islamic art is the Aga Khan Museum opening in Toronto in 2013. Led by His Highness the Aga Khan, the spiritual leader of the Shia Imami Ismaili Muslims since 1957, the museum will “will be dedicated to the acquisition, preservation and display of artefacts relating to the intellectual, cultural, artistic and religious heritage of Islamic communities,” according to its website, as well as house the collections of the Aga Khan and his family. The 100,000-square-foot museum has been design by Japanese architect Fumihiko Maki and will include a multimedia center, reference library, and auditorium.

Tagged as: Dallas Museum of Art, Islamic art, Louvre, Metropolitan Museum of Art

by Kyle Chayka on November 1, 2012

http://hyperallergic.com/59551/dallas-m ... lamic-art/

Excerpt:

Islamic art seems to be going through an international moment in the spotlight as major museums reinvigorate their collection holdings and exhibition programming of art from the Middle East. The historically conservative Louvre museum opened an entire new wing devoted to Islamic art in September of this year, though its non-traditional, non-chronological installation has been critiqued as a “visual blur and intellectual confusion” by the New York Times and a “failure to acknowlege the modern Muslim condition” by the New Statesman. The Metropolitan Museum likewise renovated its Islamic galleries in 2011 with a presentation that has been better received.

Perhaps the biggest gesture of support for the western museum-ification of Islamic art is the Aga Khan Museum opening in Toronto in 2013. Led by His Highness the Aga Khan, the spiritual leader of the Shia Imami Ismaili Muslims since 1957, the museum will “will be dedicated to the acquisition, preservation and display of artefacts relating to the intellectual, cultural, artistic and religious heritage of Islamic communities,” according to its website, as well as house the collections of the Aga Khan and his family. The 100,000-square-foot museum has been design by Japanese architect Fumihiko Maki and will include a multimedia center, reference library, and auditorium.

Tagged as: Dallas Museum of Art, Islamic art, Louvre, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Historical Images: The Blue Qur’an from the Fatimid Period, “A Very Spiritual Piece”

December 30, 2012

By Malik Merchant, Simergphotos

http://simergphotos.com/2012/12/30/hist ... ual-piece/

December 30, 2012

By Malik Merchant, Simergphotos

http://simergphotos.com/2012/12/30/hist ... ual-piece/

Good And Impressive...

The word photography is taken from Greek words photos and graphite it is the result of combining several different technical discoveries. Many people like photography i also like it very much.

Diverse Islamic Art Exhibition Opens at College

An exhibit featuring over 100 exquisite works of Islamic art is now on display at the Middlebury College Museum of Art, making it the first Islamic art exhibition in a Vermont museum in at least 30 years.

Located on the first floor of Mahaney Center for the Arts, this rich collection embodies the long history and intercontinental reach of Islamic art.

“Wondrous Worlds” features artwork in nearly all media, including ceramics, clothing, glassware, jewelry, metalworks, musical instruments, paintings, photographs, prayer rugs and textiles.

More...

https://middleburycampus.com/39827/arts ... t-college/

An exhibit featuring over 100 exquisite works of Islamic art is now on display at the Middlebury College Museum of Art, making it the first Islamic art exhibition in a Vermont museum in at least 30 years.

Located on the first floor of Mahaney Center for the Arts, this rich collection embodies the long history and intercontinental reach of Islamic art.

“Wondrous Worlds” features artwork in nearly all media, including ceramics, clothing, glassware, jewelry, metalworks, musical instruments, paintings, photographs, prayer rugs and textiles.

More...

https://middleburycampus.com/39827/arts ... t-college/

Islamic Arts Festival 2018- Houston, TX

More...

https://boniuk.rice.edu/Page.aspx?pagei ... gType=1033

More...

https://boniuk.rice.edu/Page.aspx?pagei ... gType=1033

The British Museum’s latest journey into the Islamic world started 30 years ago

The Albukhary Foundation Gallery of the Islamic World brings a rich culture to life through everyday objects

Excerpt:

We conducted a lot of focus groups to find out what our audience wanted and, as I learned, it’s a science. The overriding message was that the old gallery concentrated too much on art. The focus groups were saying: “Tell us more about the people.”

We wanted to create a gallery that brought to life the culture of the Islamic world, not just through art but everyday objects as well. There is a perception that the Islamic world is the Middle East but it is important to realise it is not just one region. It is a series of interconnected nations and continents, starting from the furthest point west in Nigeria, Africa, and stretching right across to south-east Asia. The thing that ties these regions together is the fact that Islam is the predominant religion but we also wanted to show there were people of other faiths inhabiting these regions: Christians, Jews, Hindus and Zoroastrians, among others. The arts also reflect massive upheavals across the Islamic world, such as the invasions of the Mongols from China or the Crusaders from Europe. We tried to give a nuanced story.

Bur rather than a mishmash, there is a strong structure. We present history complemented by a series of themes, such as writing and global trade. I like to think of it as a giant jigsaw puzzle. It is an attempt to tell lots of different stories, but we always start with the object. Rather than forcing a story on an object, we allow the object to tell the story.

More...

https://www.thenational.ae/opinion/comm ... o-1.794359

The Albukhary Foundation Gallery of the Islamic World brings a rich culture to life through everyday objects

Excerpt:

We conducted a lot of focus groups to find out what our audience wanted and, as I learned, it’s a science. The overriding message was that the old gallery concentrated too much on art. The focus groups were saying: “Tell us more about the people.”

We wanted to create a gallery that brought to life the culture of the Islamic world, not just through art but everyday objects as well. There is a perception that the Islamic world is the Middle East but it is important to realise it is not just one region. It is a series of interconnected nations and continents, starting from the furthest point west in Nigeria, Africa, and stretching right across to south-east Asia. The thing that ties these regions together is the fact that Islam is the predominant religion but we also wanted to show there were people of other faiths inhabiting these regions: Christians, Jews, Hindus and Zoroastrians, among others. The arts also reflect massive upheavals across the Islamic world, such as the invasions of the Mongols from China or the Crusaders from Europe. We tried to give a nuanced story.

Bur rather than a mishmash, there is a strong structure. We present history complemented by a series of themes, such as writing and global trade. I like to think of it as a giant jigsaw puzzle. It is an attempt to tell lots of different stories, but we always start with the object. Rather than forcing a story on an object, we allow the object to tell the story.

More...

https://www.thenational.ae/opinion/comm ... o-1.794359

Emperor Akbar introduced a temporary order centred on the worship of light

Posted by Nimira Dewji

The Mughals ruled the Indian subcontinent from 1526 to 1857. Muhammad Zahir al-Din Babur (r. 1526-1530) laid the foundation of a dynastic rule which inaugurated the most glorious period in the history of South Asian Islam. Babur’s grandson Jalal al-Din Muhammad Akbar (r.1556-1605), who succeed Humayun, is considered the builder of the empire. His territorial expansion, an effective fiscal policy, and most importantly his pluralistic administrative system contributed to the strong foundation of the empire.

Emperor Akber’s major project was the construction of his father’s tomb in Delhi, designed according to Timurid concepts, establishing the architectural identity of the dynasty. Restoration work on the garden tomb was completed by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, and inaugurated by Mawlana Hazar Imam and Prime Minister of India in 2013.

Humayun chahar bagh delhi aga khan

Humayun’s Tomb Complex. Photo: Archnet

Akbar also commissioned the building of several forts and mausoleums during his reign including the Agra Fort, Ajmer Fort, Lahore Fort, and Allahabad Fort.

An avid patron of the arts, Emperor Akbar established centres of artistic production for the court, illustrated manuscript studios, a translation academy, and workshops for textiles, carpets, jewellery, and metalwork. He commissioned royal manuscripts that incorporated Persian, Indian, and European elements, creating a distinct Mughal style which was further developed and refined by his successors.

Although Akbar was illiterate and possibly suffered from dyslexia, his chronicles describe him as having a “good memory for the books”1 that were read to him daily. By the year 1605, Akbar had collected 24,000 volumes, which were catalogued according to content, author, calligrapher, and language – Hindi, Persian Greek, Arabic, and Kashmiri.

In order to overcome conflicts between various religious communities, Akbar introduced a temporary order centred on the worship of light. Akbar is also credited with establishing the tradition of being weighed in gold. Twice a year, on the first day of the lunar and solar years, the emperors were weighed in gold, silver, and other precious metals as well as silk and grains; the proceeds from these went to the poor.

Concerned about the lack of an heir, Akbar sought the intervention of a Sufi saint, Sheikh Salim Chisti (d.1572). In 1569, his son and future emperor was born. In gratitude, Akbar named his son Salim, and established a walled city and an imperial palace outside Agra focused around the shrine of Sheikh Salim located in the courtyard of the Friday mosque.

Salim fatehpur sikri agra

Shrine of Sheikh Salim at Fatehpur Sikri, India. Photo: Philippa Vaughan

In 1584, Akbar moved his capital from Agra to Lahore, where he died in 1605. He was succeeded by Prince Salim who took the titles of Jahangir (“World Seizer”) and Nur al-Din (“Light of Faith”), continuing the light imagery used so frequently in his father’s metaphors of sovereignty. Akbar’s mausoleum lies in Bihishtabad (“Abode of Paradise”) outside Agra.

Akbar mughal india

Emperor Akbar’s Mausoleum. Photo: Philippa Vaughan

Sources:

1Philippa Vaughan “Decorative Arts” Islam: Art and Architecture Edited by Markus Hattstein and Peter Delius, Konnenman, p 484

Sajida S. Alvi, “Islam in South Asia.” The Muslim Almanac Edited by Azim A. Nanji, Detroit, Gale Research Inc. 1996

https://nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2019/ ... rce=Direct

Posted by Nimira Dewji

The Mughals ruled the Indian subcontinent from 1526 to 1857. Muhammad Zahir al-Din Babur (r. 1526-1530) laid the foundation of a dynastic rule which inaugurated the most glorious period in the history of South Asian Islam. Babur’s grandson Jalal al-Din Muhammad Akbar (r.1556-1605), who succeed Humayun, is considered the builder of the empire. His territorial expansion, an effective fiscal policy, and most importantly his pluralistic administrative system contributed to the strong foundation of the empire.

Emperor Akber’s major project was the construction of his father’s tomb in Delhi, designed according to Timurid concepts, establishing the architectural identity of the dynasty. Restoration work on the garden tomb was completed by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, and inaugurated by Mawlana Hazar Imam and Prime Minister of India in 2013.

Humayun chahar bagh delhi aga khan

Humayun’s Tomb Complex. Photo: Archnet

Akbar also commissioned the building of several forts and mausoleums during his reign including the Agra Fort, Ajmer Fort, Lahore Fort, and Allahabad Fort.

An avid patron of the arts, Emperor Akbar established centres of artistic production for the court, illustrated manuscript studios, a translation academy, and workshops for textiles, carpets, jewellery, and metalwork. He commissioned royal manuscripts that incorporated Persian, Indian, and European elements, creating a distinct Mughal style which was further developed and refined by his successors.

Although Akbar was illiterate and possibly suffered from dyslexia, his chronicles describe him as having a “good memory for the books”1 that were read to him daily. By the year 1605, Akbar had collected 24,000 volumes, which were catalogued according to content, author, calligrapher, and language – Hindi, Persian Greek, Arabic, and Kashmiri.

In order to overcome conflicts between various religious communities, Akbar introduced a temporary order centred on the worship of light. Akbar is also credited with establishing the tradition of being weighed in gold. Twice a year, on the first day of the lunar and solar years, the emperors were weighed in gold, silver, and other precious metals as well as silk and grains; the proceeds from these went to the poor.

Concerned about the lack of an heir, Akbar sought the intervention of a Sufi saint, Sheikh Salim Chisti (d.1572). In 1569, his son and future emperor was born. In gratitude, Akbar named his son Salim, and established a walled city and an imperial palace outside Agra focused around the shrine of Sheikh Salim located in the courtyard of the Friday mosque.

Salim fatehpur sikri agra

Shrine of Sheikh Salim at Fatehpur Sikri, India. Photo: Philippa Vaughan

In 1584, Akbar moved his capital from Agra to Lahore, where he died in 1605. He was succeeded by Prince Salim who took the titles of Jahangir (“World Seizer”) and Nur al-Din (“Light of Faith”), continuing the light imagery used so frequently in his father’s metaphors of sovereignty. Akbar’s mausoleum lies in Bihishtabad (“Abode of Paradise”) outside Agra.

Akbar mughal india

Emperor Akbar’s Mausoleum. Photo: Philippa Vaughan

Sources:

1Philippa Vaughan “Decorative Arts” Islam: Art and Architecture Edited by Markus Hattstein and Peter Delius, Konnenman, p 484

Sajida S. Alvi, “Islam in South Asia.” The Muslim Almanac Edited by Azim A. Nanji, Detroit, Gale Research Inc. 1996

https://nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2019/ ... rce=Direct

“Dream and Trauma: Reopening of the Carpet Rooms in the Museum of Islamic Art” at Pergamonmuseum, Berlin

Pergamonmuseum reopens its Carpet Rooms in the Museum of Islamic Art with an exhibition titled “Dream and Trauma.” With this permanent exhibition, the museum invites visitors to experience the origin and history of its carpet collection, and explore the museum’s current work with the carpets.

Carpets of Islamic cultures are an integral part of European cultural history. These carpets, as a testimony to the continuing cultural exchange between Europe and the Middle East, remains the focal point of the Museum of Islamic Art’s permanent exhibition.

“Dream and Trauma” has on view some of the oldest collection pieces of the museum.

“For the first time now carpets are shown, which suffered fire damage in the bombing on Berlin in 1945. The destruction of significant Persian carpets this year was a serious loss of collection. One of the fragments is the 16th century Persian animal rug, the first work of art under the number ‘I. 1’ was inventoried. Very characteristic is also the 16th century Caucasian dragon carpet, which has burn marks over its entire length of six meters. A fragrance station with a specially created smell reminiscent of charred wool, incendiary bombs and chemicals, suggests the losses of that time. And knotting technology models allow visitors to come into contact with the knots,” the museum says.

“They come from the former possession of the museum founder, Wilhelm von Bode. His interest in Islamic art as an independent and European equivalent art form was the origin of a collection that is still rare today, including carpets from today’s Turkey, Iran and the Caucasus,” the museum adds. “The measures for the preservation of the carpet collection in the post-war period are juxtaposed with today’s work in accordance with current ethical conservation and scientific standards.”

https://uk.blouinartinfo.com/news/story ... the-museum

Pergamonmuseum reopens its Carpet Rooms in the Museum of Islamic Art with an exhibition titled “Dream and Trauma.” With this permanent exhibition, the museum invites visitors to experience the origin and history of its carpet collection, and explore the museum’s current work with the carpets.

Carpets of Islamic cultures are an integral part of European cultural history. These carpets, as a testimony to the continuing cultural exchange between Europe and the Middle East, remains the focal point of the Museum of Islamic Art’s permanent exhibition.

“Dream and Trauma” has on view some of the oldest collection pieces of the museum.

“For the first time now carpets are shown, which suffered fire damage in the bombing on Berlin in 1945. The destruction of significant Persian carpets this year was a serious loss of collection. One of the fragments is the 16th century Persian animal rug, the first work of art under the number ‘I. 1’ was inventoried. Very characteristic is also the 16th century Caucasian dragon carpet, which has burn marks over its entire length of six meters. A fragrance station with a specially created smell reminiscent of charred wool, incendiary bombs and chemicals, suggests the losses of that time. And knotting technology models allow visitors to come into contact with the knots,” the museum says.

“They come from the former possession of the museum founder, Wilhelm von Bode. His interest in Islamic art as an independent and European equivalent art form was the origin of a collection that is still rare today, including carpets from today’s Turkey, Iran and the Caucasus,” the museum adds. “The measures for the preservation of the carpet collection in the post-war period are juxtaposed with today’s work in accordance with current ethical conservation and scientific standards.”

https://uk.blouinartinfo.com/news/story ... the-museum

Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah: “Poetry is the voice of God speaking through the lips of man”

Posted by Nimira Dewji

“Poetry is the voice of God speaking through the lips of man. If great painting puts you in touch with nature, great poetry puts you in direct touch with God.”

Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah’s interview with the Daily Sketch, November 2, 1931

Source: Ismaili Gnosis

In pre-Islamic times, the recitation of poetry was the mark of artistic achievement. The human voice was considered a reflection of the soul’s mysteries and feelings; instruments, then, were believed to have been created to enrich vocal music.

The oldest and simplest type of melodic rhythm, the huda, broke the silence of the desert, enchanting the lonely traveller. Other simple genres emerged, such as songs performed during the watering of animals, and other daily chores. Among the more musically developed forms were the variety of communal songs and dances at family celebrations, pilgrimages to shrines, and social evenings. Poets were said to be possessed with supernatural power, hence they were feared and revered at the same time.

Prophet Muhammad “conveyed God’s message to people in a recited form from the time the first verses were revealed to him in ca. 610 until his death in 632” (Islam An Illustrated Journey, p 75). The culture of oral tradition “suited the introduction of the Qur’an as the people of Arabia were already familiar with the spoken word” (Ibid.)

The earliest examples of religious poetry in Islam are to be found in the verses of a small group of poets who were companions of the Prophet. The most famous poet was Hassan ibn Thabit (d. 669), who wrote poems in praise of the Prophet as well as to spread the messages from the Prophet. In the years following the Prophet’s death, a number of the poets composed eulogies in his memory. The common form of poetry was the qasida – a long monorhyme (aa, ba, ca) in praise of someone although it was also used for preaching morals as well as to praise God and honour the Prophet and his family.

For the first three centuries after the emergence of Islam, the city of Medina was the musical centre with the most talented male and female singers throughout the Arabian empire, who established a school of singing that lasted for more than a century. Yunis al-Katib (d.765), a Persian singer, wrote several books on the music of the city although none of his books have survived, but they have been quoted by others.

Many women had respectable careers as musicians and singers. Koskoff reports that in “Fatimid times, there seems to have been self-employed female singers, who lived in respectable districts, sang at private parties” (Touma, The Music of the Arabs, p 72).

drummer music poetry

Carved ivory plaque with drummer Fatimid Egypt, 11th-12th century. Source: Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, Italy

As Islam spread, the music of the community became entwined with the musical traditions of the conquered lands. The elite, who were enriched by the influx of wealth, sought amusement that was best expressed in music and song. The migrants brought their art and music with them, thereby influencing local cultures. As long as it did not contradict with Islamic teaching, the people assimilated the new artistic forms creating unique styles.

The bulk of the information on music and musicians of this period comes from the monumental work Kitab al-aghani (Book of Songs) by the historian and poet Abu’l-Faradj al-Isfahani (d.967). The Book of Songs, one of the most celebrated works in Arabic literature, contains a collection of poems from the pre-Islamic period to the ninth century, all of which had been set to music along with biographical details about authors, composers, singers, and writers of music.

miniature Ikhwan rasail

Illustrated manuscript of a fragment from a tenth-century compilation of poetry set to music. Source: Met Museum

Attitudes towards music were influenced by the growth of mystics, or Sufis, who regarded poetry and music as an essential part of their devotional practices. Rabia al-Basri (ca. 717–801), considered to be the earliest Sufi saint, is widely credited with pioneering the concept of adoring the divine rather than fearing the wrath of God. Although she did not leave any written works, she was referenced by the notable Persian poet Farid al-Din Attar (d. 1225) who is believed to have possessed a lost monogram about her life. In the next century, the wrath of God was replaced by love for Him and a quest for divine union in this world.

The Safavid period (1501-1732), particularly under Shah Abbas (r.1588-1629), saw significant royal patronage of music.

dervish

The Ismaili community has had a long history in Persia, for some eight centuries from the establishment of the Nizari state of Alamut in 1090 until the migration of Imam Hasan Ali Shah Aga Khan I, in 1841.

Among the Persian-speaking Nizari Ismailis, the qasida (Persian qasideh) is an integral part of devotional literature. Nasir-i Khusraw (d. 1088-1089), considered the founder of the Ismaili communities of Central Asia, composed several qasidehs in Persian, although it is not known “how they were used in communal gatherings during his lifetime or immediately thereafter. The practice is likely to have been adopted when the Ismailis adopted Sufi traditions as taqiyya [precautionary measures] to avoid persecution […] The melodies used in [qasidehs] are based on Iranian classical music” (Music & Melodies of the Persian Ismaili Qasideh, IIS).

Aga Khan Museum Trust al-Tusi poetry music

Illustration from the Akhlaq-i Nasiri of Tusi: Musical entertainment at a scholar’s house, dated 1595, Lahore. Musicians play under the watchful eye of a master. The painting’s text is from the first discourse, ‘On Ethics’ where the author proclaims that ‘no relationship is nobler than that of equivalence as has been established in the science of music.’ Source: Spirit & Life Catalogue, Aga Khan Trust for Culture

Nizari Ismailis of the Indian subcontinent also practised concealment. Imams residing in Alamut sent da’is, or pirs, to the subcontinent to teach the Ismaili interpretation of Islam to non-Arabic speaking people beginning in the eleventh century. At the time, the field of devotional poetry was flourishing in the subcontinent, hence, the pirs used poetic compositions to spread the message. The ginans were a counterpart to the traditions of the geet, bhajan, and kirtan along with mystical poetry developing among the Sufis in the subcontinent.

ginans pir shams

Vaek Moto attributed to Pir Shams copied in 1841 by Dahio Surijiani. Pir Shams extols the virtues of knowledge, ‘ilm, and urges the faithful to plumb the depths of esoteric wisdom conveyed by the Imams. Source: The Institute of Ismaili Studies

From the Sanskrit jnana meaning ‘contemplative knowledge,’ ginans are a vast corpus of poetic compositions in the languages of the respective local regions enabling the composers to use local music styles to sing their poetry. Compositions were also influenced by the various communities’ needs to assimilate the practices of the dominant local community in order to avoid persecution. Hence ginans were composed in Sindhi, Gujarati, Kuchhi, Multani, Hindi, and Panjabi. About thirty da’is composed ginans over a period of six centuries.

Like most Indian devotional poetry, ginans are meant to be sung. Music, therefore, is a vital characteristic of ginans to invoke specific emotional states such as on special occasions, morning prayers, evening prayers, ghatpat ceremony, or at funerals.

Through the poetic medium of ginans, the pirs provided guidance on a variety of doctrinal, ethical, and mystical themes for the community, facilitating the journey to spiritual ecstasy.

Ginan bolore nit nure bharea; evo haide tamare harakh na maeji.

Recite continually the Ginans which are filled with light;

boundless will be the joy in your heart. (tr. by Ali Asani). Listen

Sources:

Ali S. Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment, The Ismaili Devotional Literature of South Asia, I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd., London, 2002

Amnon Shiloah, Music in the World of Islam, Wayne State University Press, Detroit, 1995

Habib Hassan Touma, The Music of the Arabs, Amadeus Press, Portland Oregon, 1996

Farhad Daftary, Zulfikar Hirji, Islam An Illustrated Journey, Azimuth Editions in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2018

Ginans: A Tradition of Religious Poetry, The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Music & Melodies of the Persian Ismaili Qasideh, The Institute of Ismaili Studies

https://nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2019/ ... ps-of-man/

Posted by Nimira Dewji

“Poetry is the voice of God speaking through the lips of man. If great painting puts you in touch with nature, great poetry puts you in direct touch with God.”

Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah’s interview with the Daily Sketch, November 2, 1931

Source: Ismaili Gnosis

In pre-Islamic times, the recitation of poetry was the mark of artistic achievement. The human voice was considered a reflection of the soul’s mysteries and feelings; instruments, then, were believed to have been created to enrich vocal music.

The oldest and simplest type of melodic rhythm, the huda, broke the silence of the desert, enchanting the lonely traveller. Other simple genres emerged, such as songs performed during the watering of animals, and other daily chores. Among the more musically developed forms were the variety of communal songs and dances at family celebrations, pilgrimages to shrines, and social evenings. Poets were said to be possessed with supernatural power, hence they were feared and revered at the same time.

Prophet Muhammad “conveyed God’s message to people in a recited form from the time the first verses were revealed to him in ca. 610 until his death in 632” (Islam An Illustrated Journey, p 75). The culture of oral tradition “suited the introduction of the Qur’an as the people of Arabia were already familiar with the spoken word” (Ibid.)

The earliest examples of religious poetry in Islam are to be found in the verses of a small group of poets who were companions of the Prophet. The most famous poet was Hassan ibn Thabit (d. 669), who wrote poems in praise of the Prophet as well as to spread the messages from the Prophet. In the years following the Prophet’s death, a number of the poets composed eulogies in his memory. The common form of poetry was the qasida – a long monorhyme (aa, ba, ca) in praise of someone although it was also used for preaching morals as well as to praise God and honour the Prophet and his family.

For the first three centuries after the emergence of Islam, the city of Medina was the musical centre with the most talented male and female singers throughout the Arabian empire, who established a school of singing that lasted for more than a century. Yunis al-Katib (d.765), a Persian singer, wrote several books on the music of the city although none of his books have survived, but they have been quoted by others.

Many women had respectable careers as musicians and singers. Koskoff reports that in “Fatimid times, there seems to have been self-employed female singers, who lived in respectable districts, sang at private parties” (Touma, The Music of the Arabs, p 72).

drummer music poetry

Carved ivory plaque with drummer Fatimid Egypt, 11th-12th century. Source: Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, Italy

As Islam spread, the music of the community became entwined with the musical traditions of the conquered lands. The elite, who were enriched by the influx of wealth, sought amusement that was best expressed in music and song. The migrants brought their art and music with them, thereby influencing local cultures. As long as it did not contradict with Islamic teaching, the people assimilated the new artistic forms creating unique styles.

The bulk of the information on music and musicians of this period comes from the monumental work Kitab al-aghani (Book of Songs) by the historian and poet Abu’l-Faradj al-Isfahani (d.967). The Book of Songs, one of the most celebrated works in Arabic literature, contains a collection of poems from the pre-Islamic period to the ninth century, all of which had been set to music along with biographical details about authors, composers, singers, and writers of music.

miniature Ikhwan rasail

Illustrated manuscript of a fragment from a tenth-century compilation of poetry set to music. Source: Met Museum

Attitudes towards music were influenced by the growth of mystics, or Sufis, who regarded poetry and music as an essential part of their devotional practices. Rabia al-Basri (ca. 717–801), considered to be the earliest Sufi saint, is widely credited with pioneering the concept of adoring the divine rather than fearing the wrath of God. Although she did not leave any written works, she was referenced by the notable Persian poet Farid al-Din Attar (d. 1225) who is believed to have possessed a lost monogram about her life. In the next century, the wrath of God was replaced by love for Him and a quest for divine union in this world.

The Safavid period (1501-1732), particularly under Shah Abbas (r.1588-1629), saw significant royal patronage of music.

dervish

The Ismaili community has had a long history in Persia, for some eight centuries from the establishment of the Nizari state of Alamut in 1090 until the migration of Imam Hasan Ali Shah Aga Khan I, in 1841.

Among the Persian-speaking Nizari Ismailis, the qasida (Persian qasideh) is an integral part of devotional literature. Nasir-i Khusraw (d. 1088-1089), considered the founder of the Ismaili communities of Central Asia, composed several qasidehs in Persian, although it is not known “how they were used in communal gatherings during his lifetime or immediately thereafter. The practice is likely to have been adopted when the Ismailis adopted Sufi traditions as taqiyya [precautionary measures] to avoid persecution […] The melodies used in [qasidehs] are based on Iranian classical music” (Music & Melodies of the Persian Ismaili Qasideh, IIS).

Aga Khan Museum Trust al-Tusi poetry music

Illustration from the Akhlaq-i Nasiri of Tusi: Musical entertainment at a scholar’s house, dated 1595, Lahore. Musicians play under the watchful eye of a master. The painting’s text is from the first discourse, ‘On Ethics’ where the author proclaims that ‘no relationship is nobler than that of equivalence as has been established in the science of music.’ Source: Spirit & Life Catalogue, Aga Khan Trust for Culture

Nizari Ismailis of the Indian subcontinent also practised concealment. Imams residing in Alamut sent da’is, or pirs, to the subcontinent to teach the Ismaili interpretation of Islam to non-Arabic speaking people beginning in the eleventh century. At the time, the field of devotional poetry was flourishing in the subcontinent, hence, the pirs used poetic compositions to spread the message. The ginans were a counterpart to the traditions of the geet, bhajan, and kirtan along with mystical poetry developing among the Sufis in the subcontinent.

ginans pir shams

Vaek Moto attributed to Pir Shams copied in 1841 by Dahio Surijiani. Pir Shams extols the virtues of knowledge, ‘ilm, and urges the faithful to plumb the depths of esoteric wisdom conveyed by the Imams. Source: The Institute of Ismaili Studies

From the Sanskrit jnana meaning ‘contemplative knowledge,’ ginans are a vast corpus of poetic compositions in the languages of the respective local regions enabling the composers to use local music styles to sing their poetry. Compositions were also influenced by the various communities’ needs to assimilate the practices of the dominant local community in order to avoid persecution. Hence ginans were composed in Sindhi, Gujarati, Kuchhi, Multani, Hindi, and Panjabi. About thirty da’is composed ginans over a period of six centuries.

Like most Indian devotional poetry, ginans are meant to be sung. Music, therefore, is a vital characteristic of ginans to invoke specific emotional states such as on special occasions, morning prayers, evening prayers, ghatpat ceremony, or at funerals.

Through the poetic medium of ginans, the pirs provided guidance on a variety of doctrinal, ethical, and mystical themes for the community, facilitating the journey to spiritual ecstasy.

Ginan bolore nit nure bharea; evo haide tamare harakh na maeji.

Recite continually the Ginans which are filled with light;

boundless will be the joy in your heart. (tr. by Ali Asani). Listen

Sources:

Ali S. Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment, The Ismaili Devotional Literature of South Asia, I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd., London, 2002

Amnon Shiloah, Music in the World of Islam, Wayne State University Press, Detroit, 1995

Habib Hassan Touma, The Music of the Arabs, Amadeus Press, Portland Oregon, 1996

Farhad Daftary, Zulfikar Hirji, Islam An Illustrated Journey, Azimuth Editions in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2018

Ginans: A Tradition of Religious Poetry, The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Music & Melodies of the Persian Ismaili Qasideh, The Institute of Ismaili Studies

https://nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2019/ ... ps-of-man/

Separating fact and fiction in Islamic art

Stephennie Mulder aims to expand the usual ‘European story’ and outlook on art history

Last week Stephennie Mulder, who teaches the history of Islamic Art and Architecture at the University of Texas at Austin, was in Ireland to deliver the annual Chester Beatty lecture.

The subject was her multiple-award-winning book, The Shrines of the ‘Alids in Medieval Syria. Originally published in 2014, the volume has just been published in a paperback edition – the hardback sold out and is currently being reprinted.

At first glance it may seem like a niche subject, yet it has attracted a great deal of attention beyond academic circles. As Mulder is keen to emphasise, it has much greater resonance than you might expect, in the context of the recent history of the Middle East, and the general misapprehension of Islamic culture in the West.

Originally from Salt Lake City, Mulder began her studies, which eventually encompassed art history, archaeology, anthropology and Arabic, in Utah, and went on to Princeton and Pennsylvania (she’s been teaching in Austin since 2008). What prompted her interest in Islamic art and culture?

“It’s really simple. I took a class in Islamic civilization and I realied immediately that it was something that had been missing from my education. I mean, I knew China and India had long, rich histories, for example, but the Islamic world, in contrast, had been largely written out of the history we were taught. My history of art textbook had 17 pages on Islamic art in its totality, and about 60 on ancient Roman art alone.”

More....

https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/art- ... -1.3787110

Stephennie Mulder aims to expand the usual ‘European story’ and outlook on art history

Last week Stephennie Mulder, who teaches the history of Islamic Art and Architecture at the University of Texas at Austin, was in Ireland to deliver the annual Chester Beatty lecture.

The subject was her multiple-award-winning book, The Shrines of the ‘Alids in Medieval Syria. Originally published in 2014, the volume has just been published in a paperback edition – the hardback sold out and is currently being reprinted.

At first glance it may seem like a niche subject, yet it has attracted a great deal of attention beyond academic circles. As Mulder is keen to emphasise, it has much greater resonance than you might expect, in the context of the recent history of the Middle East, and the general misapprehension of Islamic culture in the West.

Originally from Salt Lake City, Mulder began her studies, which eventually encompassed art history, archaeology, anthropology and Arabic, in Utah, and went on to Princeton and Pennsylvania (she’s been teaching in Austin since 2008). What prompted her interest in Islamic art and culture?

“It’s really simple. I took a class in Islamic civilization and I realied immediately that it was something that had been missing from my education. I mean, I knew China and India had long, rich histories, for example, but the Islamic world, in contrast, had been largely written out of the history we were taught. My history of art textbook had 17 pages on Islamic art in its totality, and about 60 on ancient Roman art alone.”

More....

https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/art- ... -1.3787110

Art and Music in Muslim contexts

The 13th century Sufi poet Jalal al-Din Rumi once said, “Inside you there’s an artist you don’t know about…” perhaps hinting at the reality that, while consumed by the responsibilities and distractions of daily life, many of us are yet to find the creative gifts that lie hidden within.

Art can act as a universal language, enhancing understanding of one’s own or another’s culture, by telling a story about a particular time or place. Various pieces of art come together to define the distinct ‘culture’ of a given society and include diverse forms, such as painting, music, literature, dance, poetry, and landscape planning. Art can also encourage us to look inside ourselves, to search for personal passions, and to take a wider perspective in seeing the world.

Mawlana Hazar Imam has spoken of the importance of art on a number of occasions. In the foreword of Spirit and Life, published in 2007, he stated that “The arts have always had a special significance for my family. More than a thousand years ago my ancestors, the Fatimid Imams, encouraged patronage of the arts and fostered the creation of collections of outstanding works of arts and libraries of rare and significant manuscripts… I believe that these works all contribute to an understanding of some of the aesthetic values which underpin Muslim arts and the humanistic traditions of Islam.”

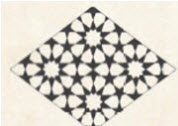

The Fatimids (909-1171 CE), were one of several Muslim dynasties that celebrated and promoted the arts. During their reign over North Africa and parts of the Mediterranean, and particularly in Egypt, they harnessed an eclectic spirit, combining diverse influences to create exciting new art forms. These included building styles from the Roman Empire and mosaic designs from the Iberian Peninsula to ceramics from the Far East and calligraphy from the Persian Gulf. This pluralistic approach is today regarded among historians as one of the most creative eras in Islamic history.

Throughout this vast history, the artwork of Muslim societies has played an important role in reminding the world that beauty is significant. The elegant appeal of historic buildings and gardens, miniature paintings, opulent carpets, and crystal ware, for example, have been ways in which artists have recognised the splendour of the world, and are also a reflection of the Islamic tradition which gives beauty its own intrinsic value.

Beauty can be conveyed through aesthetic or acoustic forms, or a combination of the two. The art of music uses acoustics to tell a story. Age-old tales have been passed down for generations in the form of song and verse, from the Middle East and North and West Africa, to South and Central Asia. A constellation of devotional music and poetry, of indigenous classical, traditional folk, and tradition-inspired contemporary music has since flourished over time in cultures shaped by Islam.

In a poem entitled Where everything is music, Rumi writes,

We have fallen into the place

where everything is music.

The strumming and the flute notes

rise into the atmosphere,

and even if the whole world’s harp

should burn up, there will still be

hidden instruments playing, playing.

So the candle flickers and goes out.

We have a piece of flint, and a spark.

This singing art is sea foam.

The graceful movements come from a pearl

somewhere on the ocean floor.

The medium of music has played a prominent role in building bridges between diverse peoples, through creating understanding and empathy. The inherent human trait of curiosity and attraction to novelty has encouraged the spread of various types of music from one part of the world to another. For instance, the historic Silk Route, a trading passage of historical significance, once connected the far reaches of China with the Mediterranean, via the high mountains and picturesque landscapes of Central Asia. Groups of merchants, pilgrims, and travellers navigated their way back and forth across the route to trade and exchange silks, spices, silver, stories, and songs.

The sounds that moved along the route exemplify the way musical creativity has historically developed from the meeting of different cultures. The percussion, string, and wind instruments of the time are thought to have been later adapted into modern day instruments such as the familiar drum, violin, and flute.

Illustrating his commitment to creative expressions, Mawlana Hazar Imam has established the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, the Aga Khan Music Initiative (AKMI), and the Aga Khan Museum, in an effort to re-invigorate interest in the arts and to preserve, promote, and develop the cultural heritage of Muslim societies and civilisations. Since launching 19 years ago, AKMI has become an interregional music and arts education programme with worldwide performances as well as outreach, mentoring, and artistic production activities. Later this month, the very first Aga Khan Music Awards will be held in Lisbon, Portugal.

Like the human heart, music follows a beat. The mingling of words and sounds can sift through obscure depths of feeling. Along with other forms of art, it triggers memories both distinct and dormant, and can articulate emotions previously unknown. As we enter into spring — the season of new beginnings — we are offered an opportunity to more fully appreciate the beauty of the world, to search for undiscovered gifts, and to seek out the artist hidden within.

https://the.ismaili/our-stories/art-and ... m-contexts

The 13th century Sufi poet Jalal al-Din Rumi once said, “Inside you there’s an artist you don’t know about…” perhaps hinting at the reality that, while consumed by the responsibilities and distractions of daily life, many of us are yet to find the creative gifts that lie hidden within.

Art can act as a universal language, enhancing understanding of one’s own or another’s culture, by telling a story about a particular time or place. Various pieces of art come together to define the distinct ‘culture’ of a given society and include diverse forms, such as painting, music, literature, dance, poetry, and landscape planning. Art can also encourage us to look inside ourselves, to search for personal passions, and to take a wider perspective in seeing the world.

Mawlana Hazar Imam has spoken of the importance of art on a number of occasions. In the foreword of Spirit and Life, published in 2007, he stated that “The arts have always had a special significance for my family. More than a thousand years ago my ancestors, the Fatimid Imams, encouraged patronage of the arts and fostered the creation of collections of outstanding works of arts and libraries of rare and significant manuscripts… I believe that these works all contribute to an understanding of some of the aesthetic values which underpin Muslim arts and the humanistic traditions of Islam.”

The Fatimids (909-1171 CE), were one of several Muslim dynasties that celebrated and promoted the arts. During their reign over North Africa and parts of the Mediterranean, and particularly in Egypt, they harnessed an eclectic spirit, combining diverse influences to create exciting new art forms. These included building styles from the Roman Empire and mosaic designs from the Iberian Peninsula to ceramics from the Far East and calligraphy from the Persian Gulf. This pluralistic approach is today regarded among historians as one of the most creative eras in Islamic history.

Throughout this vast history, the artwork of Muslim societies has played an important role in reminding the world that beauty is significant. The elegant appeal of historic buildings and gardens, miniature paintings, opulent carpets, and crystal ware, for example, have been ways in which artists have recognised the splendour of the world, and are also a reflection of the Islamic tradition which gives beauty its own intrinsic value.

Beauty can be conveyed through aesthetic or acoustic forms, or a combination of the two. The art of music uses acoustics to tell a story. Age-old tales have been passed down for generations in the form of song and verse, from the Middle East and North and West Africa, to South and Central Asia. A constellation of devotional music and poetry, of indigenous classical, traditional folk, and tradition-inspired contemporary music has since flourished over time in cultures shaped by Islam.

In a poem entitled Where everything is music, Rumi writes,

We have fallen into the place

where everything is music.

The strumming and the flute notes

rise into the atmosphere,

and even if the whole world’s harp

should burn up, there will still be

hidden instruments playing, playing.

So the candle flickers and goes out.

We have a piece of flint, and a spark.

This singing art is sea foam.

The graceful movements come from a pearl

somewhere on the ocean floor.

The medium of music has played a prominent role in building bridges between diverse peoples, through creating understanding and empathy. The inherent human trait of curiosity and attraction to novelty has encouraged the spread of various types of music from one part of the world to another. For instance, the historic Silk Route, a trading passage of historical significance, once connected the far reaches of China with the Mediterranean, via the high mountains and picturesque landscapes of Central Asia. Groups of merchants, pilgrims, and travellers navigated their way back and forth across the route to trade and exchange silks, spices, silver, stories, and songs.

The sounds that moved along the route exemplify the way musical creativity has historically developed from the meeting of different cultures. The percussion, string, and wind instruments of the time are thought to have been later adapted into modern day instruments such as the familiar drum, violin, and flute.

Illustrating his commitment to creative expressions, Mawlana Hazar Imam has established the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, the Aga Khan Music Initiative (AKMI), and the Aga Khan Museum, in an effort to re-invigorate interest in the arts and to preserve, promote, and develop the cultural heritage of Muslim societies and civilisations. Since launching 19 years ago, AKMI has become an interregional music and arts education programme with worldwide performances as well as outreach, mentoring, and artistic production activities. Later this month, the very first Aga Khan Music Awards will be held in Lisbon, Portugal.

Like the human heart, music follows a beat. The mingling of words and sounds can sift through obscure depths of feeling. Along with other forms of art, it triggers memories both distinct and dormant, and can articulate emotions previously unknown. As we enter into spring — the season of new beginnings — we are offered an opportunity to more fully appreciate the beauty of the world, to search for undiscovered gifts, and to seek out the artist hidden within.

https://the.ismaili/our-stories/art-and ... m-contexts

In Knowledge Societies, the study of music was obligatory for the learned

Posted by Nimira Dewji

“The fundamental reason for the pre-eminence of Islamic civilizations lay neither in accidents of history nor in acts of war, but rather in their ability to discover new knowledge, to make it their own, and to build constructively upon it. They became the Knowledge Societies of their time…The spirit of the Knowledge Society is the spirit of Pluralism—a readiness to accept the other, indeed to learn from him, to see difference as an opportunity rather than a threat.”

Mawlana Hazar Imam

Speech

In pre-Islamic times, the recitation of poetry was the mark of artistic achievement. The prevalent form was the qasida – a long monorhyme (aa, ba, ca) that was used in praise of someone or basic rhetoric. Subsequently, it was used to teach morals as well as praise God and the Prophet.

An important aspect was the growing awareness of the potential expressiveness of the human voice, considered a reflection of the soul’s mysteries and feelings. As Islam spread, the music of the various communities became entwined with the traditions of the conquered lands.

The elite, who were enriched by the influx of wealth, sought amusement that was best expressed in song and music. New artistic forms emerged elevating the status of musicians and singers including women, who were known as qayna, who received their musical training from the most famous musicians of the day. Hence the accomplished qayna could “conduct gracious conversations with guests and gladden their hearts with songs and instrumental music” (Shiloah, Music in the World of Islam p 30). Some of the accomplished artists include Khawla bint al-Azwar (7th century), Azza al-Maila (d. ca. 707), Atika bint Shuhda ( 8th century), among others.

For the first three centuries after the emergence of Islam, Medina became a musical centre in the Arabian peninsula attracting talented artists noted in some of the earliest surviving works on music including the Book of Melodies by the esteemed poet Yunus al-Katib (d. 765), Book of Diversion and Musical Instruments by Abu’l Qasim Ubayd Allah (d. 911), and Meadows of Gold and Mines of Gems by al-Mas’udi (d. 956). In his Book of Songs, one of the most celebrated works in Arabic literature, the poet and historian Abu’l-Faradj al-Isfahani (d. 967) compiled a collection of poems from the pre-Islamic period to the ninth century, all set to music along with biographical details about the authors, composers, and singers. He noted that “in a society avid for knowledge the study of music became obligatory for every learned person; music was one of the topics frequently discussed by people in all walks of life ” (Shiloah, Music in the World of Islam p 26).

music Nasir Tusi AKTC

Illustration of musical entertainment at a scholar’s house, Lahore, ca. 1595. The painting is from Mughal Emperor Akbar’s (r. 1556-1605) favourite manuscripts, the Akhlaq-i Nasiri (The Ethics of Nasir). Source: Spirit & Life Catalogue, Aga Khan Trust for Culture

The prose writer al-Djahiz (d. ca. 868-9), in his masterpiece the Book of Animals, discusses the “characteristics of sounds and the effect of music on the souls of men and animals (Shiloah, Music in the World of Islam p 25).

Ya’qub ibn Ishaq al-Kindi (d. ca. 870), a philosopher, mathematician, physician, and musician, included music in the mathematical sciences that “prepare the student for higher studies of philosophy and for knowledge of the wonders of creation…The science of harmony in its broadest sense is central for understanding the complex network linking music to all attributes of the universe” (Shiloah, Music in the World of Islam p 49). Al-Kindi, in his work Book of Sounds Made by Instruments Having One to Ten Strings, explains that instruments help create harmony between the soul and the universe.

Al-Kindi’s theory was further developed by the Ikhwan al-Safa (Brethren of Purity), an anonymous tenth-century group of authors based in Basra and Baghdad, Iraq, who compiled an encyclopedic work – Rasa’il Ikhwan al-Safa’ (Epistles of the Brethren of Purity). Seeking to show compatibility of Islam with other religions and intellectual traditions, the Ikhwan drew on diverse schools of wisdom including Babylonian, Greek, Persian, and Indian traditions.

The Ikhwan occupied a prominent position in the history of scientific and philosophical ideas in Islam owing to the wide intellectual reception and dissemination of diverse manuscripts of their Rasa’il.

Although the exact date of the Rasa’il and the identities of its authors remain a mystery, some historians situate this brotherhood to the eighth century, attributing the compiling of the Rasa’il to the early Ismaili Imams Jafar al-Sadiq, Abd Allah (Wafi Ahmed), or his son Ahmad b. Abd Allal (al-Taqi); others situate the Ikhwan to just before the founding of the Fatimid dynasty in North Africa in 909. Daftary notes that the Ismaili origin of the Rasa’il was recognised by Paul Casanova in 1898, “long before the modern recovery of Isma’ili literature” (The Ismai’ilis their History and Doctrines p 246).

Ikhwan

The Institute of Ismaili Studies

In the section on music, the Ikhwan discuss that “musical tones [naghamat] have a spiritual effect on souls” (Epistles, “On Music,” p 84). Music, notes the Ikhwan, “reflects the harmonious beauty of the universe… Musical harmony conceived according to the laws of the well-ordered universe helps man in his attempt to achieve spiritual and philosophical equilibrium…the proper use of music at the right time has a healing influence on the body” (Shiloah, Music in the World of Islam, p 50). The Ikhwan devote special section to the making and tuning of instruments.

tar Persian music

A youth playing a tar, one of the most important classical Persian instruments. The melodies performed on the tar were thought to have a calming effect on people. Source: Spirit & Life Catalogue, Aga Khan Trust for Culture

In his work The Ethics of Nasir, a philosophical treatise on ethics, social justice, and politics, the Persian philosopher Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (d. 1274) proclaims that after the nearness to God, ‘no relationship is nobler than that of equivalence as has been established in the science of music’ (Spirit & Life Catalogue p 167).

Sources:

Music in Islam

Epistles of the Brethren of Purity, “On Music,” Edited and Translated by Owen Wright, Oxford University Press in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2010

Amnon Shiloah. Music in the World of Islam. Wayne State University Press. Detroit.1995

From the Manuscript Tradition to the Printed Text: The Transmission of the Rasa’il of the Ikhwan al-Safa’ in the East and West, The Institute of Ismaili Studies

nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2019/03/29/in-knowledge-societies-the-study-of-music-was-obligatory-for-the-learned/

Posted by Nimira Dewji

“The fundamental reason for the pre-eminence of Islamic civilizations lay neither in accidents of history nor in acts of war, but rather in their ability to discover new knowledge, to make it their own, and to build constructively upon it. They became the Knowledge Societies of their time…The spirit of the Knowledge Society is the spirit of Pluralism—a readiness to accept the other, indeed to learn from him, to see difference as an opportunity rather than a threat.”

Mawlana Hazar Imam

Speech

In pre-Islamic times, the recitation of poetry was the mark of artistic achievement. The prevalent form was the qasida – a long monorhyme (aa, ba, ca) that was used in praise of someone or basic rhetoric. Subsequently, it was used to teach morals as well as praise God and the Prophet.

An important aspect was the growing awareness of the potential expressiveness of the human voice, considered a reflection of the soul’s mysteries and feelings. As Islam spread, the music of the various communities became entwined with the traditions of the conquered lands.

The elite, who were enriched by the influx of wealth, sought amusement that was best expressed in song and music. New artistic forms emerged elevating the status of musicians and singers including women, who were known as qayna, who received their musical training from the most famous musicians of the day. Hence the accomplished qayna could “conduct gracious conversations with guests and gladden their hearts with songs and instrumental music” (Shiloah, Music in the World of Islam p 30). Some of the accomplished artists include Khawla bint al-Azwar (7th century), Azza al-Maila (d. ca. 707), Atika bint Shuhda ( 8th century), among others.

For the first three centuries after the emergence of Islam, Medina became a musical centre in the Arabian peninsula attracting talented artists noted in some of the earliest surviving works on music including the Book of Melodies by the esteemed poet Yunus al-Katib (d. 765), Book of Diversion and Musical Instruments by Abu’l Qasim Ubayd Allah (d. 911), and Meadows of Gold and Mines of Gems by al-Mas’udi (d. 956). In his Book of Songs, one of the most celebrated works in Arabic literature, the poet and historian Abu’l-Faradj al-Isfahani (d. 967) compiled a collection of poems from the pre-Islamic period to the ninth century, all set to music along with biographical details about the authors, composers, and singers. He noted that “in a society avid for knowledge the study of music became obligatory for every learned person; music was one of the topics frequently discussed by people in all walks of life ” (Shiloah, Music in the World of Islam p 26).

music Nasir Tusi AKTC

Illustration of musical entertainment at a scholar’s house, Lahore, ca. 1595. The painting is from Mughal Emperor Akbar’s (r. 1556-1605) favourite manuscripts, the Akhlaq-i Nasiri (The Ethics of Nasir). Source: Spirit & Life Catalogue, Aga Khan Trust for Culture

The prose writer al-Djahiz (d. ca. 868-9), in his masterpiece the Book of Animals, discusses the “characteristics of sounds and the effect of music on the souls of men and animals (Shiloah, Music in the World of Islam p 25).

Ya’qub ibn Ishaq al-Kindi (d. ca. 870), a philosopher, mathematician, physician, and musician, included music in the mathematical sciences that “prepare the student for higher studies of philosophy and for knowledge of the wonders of creation…The science of harmony in its broadest sense is central for understanding the complex network linking music to all attributes of the universe” (Shiloah, Music in the World of Islam p 49). Al-Kindi, in his work Book of Sounds Made by Instruments Having One to Ten Strings, explains that instruments help create harmony between the soul and the universe.

Al-Kindi’s theory was further developed by the Ikhwan al-Safa (Brethren of Purity), an anonymous tenth-century group of authors based in Basra and Baghdad, Iraq, who compiled an encyclopedic work – Rasa’il Ikhwan al-Safa’ (Epistles of the Brethren of Purity). Seeking to show compatibility of Islam with other religions and intellectual traditions, the Ikhwan drew on diverse schools of wisdom including Babylonian, Greek, Persian, and Indian traditions.

The Ikhwan occupied a prominent position in the history of scientific and philosophical ideas in Islam owing to the wide intellectual reception and dissemination of diverse manuscripts of their Rasa’il.

Although the exact date of the Rasa’il and the identities of its authors remain a mystery, some historians situate this brotherhood to the eighth century, attributing the compiling of the Rasa’il to the early Ismaili Imams Jafar al-Sadiq, Abd Allah (Wafi Ahmed), or his son Ahmad b. Abd Allal (al-Taqi); others situate the Ikhwan to just before the founding of the Fatimid dynasty in North Africa in 909. Daftary notes that the Ismaili origin of the Rasa’il was recognised by Paul Casanova in 1898, “long before the modern recovery of Isma’ili literature” (The Ismai’ilis their History and Doctrines p 246).

Ikhwan

The Institute of Ismaili Studies

In the section on music, the Ikhwan discuss that “musical tones [naghamat] have a spiritual effect on souls” (Epistles, “On Music,” p 84). Music, notes the Ikhwan, “reflects the harmonious beauty of the universe… Musical harmony conceived according to the laws of the well-ordered universe helps man in his attempt to achieve spiritual and philosophical equilibrium…the proper use of music at the right time has a healing influence on the body” (Shiloah, Music in the World of Islam, p 50). The Ikhwan devote special section to the making and tuning of instruments.

tar Persian music

A youth playing a tar, one of the most important classical Persian instruments. The melodies performed on the tar were thought to have a calming effect on people. Source: Spirit & Life Catalogue, Aga Khan Trust for Culture

In his work The Ethics of Nasir, a philosophical treatise on ethics, social justice, and politics, the Persian philosopher Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (d. 1274) proclaims that after the nearness to God, ‘no relationship is nobler than that of equivalence as has been established in the science of music’ (Spirit & Life Catalogue p 167).

Sources:

Music in Islam

Epistles of the Brethren of Purity, “On Music,” Edited and Translated by Owen Wright, Oxford University Press in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2010

Amnon Shiloah. Music in the World of Islam. Wayne State University Press. Detroit.1995

From the Manuscript Tradition to the Printed Text: The Transmission of the Rasa’il of the Ikhwan al-Safa’ in the East and West, The Institute of Ismaili Studies

nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2019/03/29/in-knowledge-societies-the-study-of-music-was-obligatory-for-the-learned/

Exhibition:

NOMADIC TRACES: JOURNEYS OF ARABIAN SCRIPTS

16 March 2019 - 28 July 2019

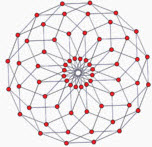

The Middle East has been a cradle of several civilizations (religions, languages, and traditions), and a site of crossing trade routes that transcended modern national borders and identities. Not only goods, but also knowledge has over the centuries crossed the permeable borders along the caravan routes, as people spoke and wrote in several languages, borrowed from each other, and adapted ideas and skills to their respective needs. The story of written scripts in the Middle East testifies to this cultural wealth, diversity and fluidity.

The exhibition, Nomadic Traces: Journeys of Arabian Scripts, reflects on the important role that scripts have played in defining and preserving the cultural identity of past and present civilizations, and on the migrational and transformative nature of writing and its ability to freely cross borders and cultures. The exhibition sheds light on the development of some of the key Abjads (consonantal alphabets) of the Middle East. It poetically links the past with the present, showing in particular the wealth of this region through its many scripts, including Phoenician, Aramaic, Musnad, Palmyrene, Nabatean, and early Arabic (Jazm).

These writing systems are the binding agents of this exhibition. They constitute the core material for the production of newly-commissioned works by artists and designers of various nationalities (including the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon and Palestine) and specializations. The works reflect on and interpret with text and form the notion of ‘contemporary nomads’, referencing traditional crafts and exploring their potential for contemporary design. The featured works include art installations, jewelry, fashion, textiles, furniture and product design, and ceramics.

Featured artists and designers: Nasser Al-Salem, Sarah Al-Agroobi, Nadine Kanso, Ghita Abi-Hanna, Milia Maroun, Khalid Mezaina, Rasha Dakkak, Hamza Omari, and Xeina Al-Malki

Reasearch team: Ranim Al-Halaky, Dina Khorchid, Sheikha and Afra Bin Dhaher

This exhibition will run until 28.07.2019

In partnership with Khatt Foundation

https://www.warehouse421.ae/en/exhibiti ... n-scripts/

NOMADIC TRACES: JOURNEYS OF ARABIAN SCRIPTS

16 March 2019 - 28 July 2019

The Middle East has been a cradle of several civilizations (religions, languages, and traditions), and a site of crossing trade routes that transcended modern national borders and identities. Not only goods, but also knowledge has over the centuries crossed the permeable borders along the caravan routes, as people spoke and wrote in several languages, borrowed from each other, and adapted ideas and skills to their respective needs. The story of written scripts in the Middle East testifies to this cultural wealth, diversity and fluidity.

The exhibition, Nomadic Traces: Journeys of Arabian Scripts, reflects on the important role that scripts have played in defining and preserving the cultural identity of past and present civilizations, and on the migrational and transformative nature of writing and its ability to freely cross borders and cultures. The exhibition sheds light on the development of some of the key Abjads (consonantal alphabets) of the Middle East. It poetically links the past with the present, showing in particular the wealth of this region through its many scripts, including Phoenician, Aramaic, Musnad, Palmyrene, Nabatean, and early Arabic (Jazm).

These writing systems are the binding agents of this exhibition. They constitute the core material for the production of newly-commissioned works by artists and designers of various nationalities (including the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon and Palestine) and specializations. The works reflect on and interpret with text and form the notion of ‘contemporary nomads’, referencing traditional crafts and exploring their potential for contemporary design. The featured works include art installations, jewelry, fashion, textiles, furniture and product design, and ceramics.

Featured artists and designers: Nasser Al-Salem, Sarah Al-Agroobi, Nadine Kanso, Ghita Abi-Hanna, Milia Maroun, Khalid Mezaina, Rasha Dakkak, Hamza Omari, and Xeina Al-Malki

Reasearch team: Ranim Al-Halaky, Dina Khorchid, Sheikha and Afra Bin Dhaher

This exhibition will run until 28.07.2019

In partnership with Khatt Foundation

https://www.warehouse421.ae/en/exhibiti ... n-scripts/

Book

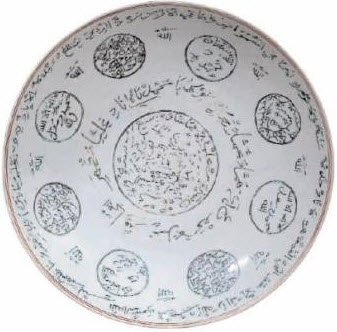

Qajar Ceramics: Bridging Tradition and Modernity

The Qajar era (1785–1925) was a time of struggle to maintain Persian tradition and identity while embracing innovation and modernity. The rarely explored field of Qajar ceramics typifies the development of the dynasty’s own language and vitality, reflecting the rich vigour of the time. Qajar Ceramics – Bridging Tradition and Modernity is about art in transition, featuring a diversity of ceramic objects from the collection of the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia. Both the publication and the exhibition offer a closer look at the distinctive characteristics of Qajar ceramics, highlighting their forms, aesthetics and themes. Going further, the publication delves into historical sources, revealing newly discovered and important treatises on ceramic artists and kiln technology. Leading authorities have provided essays that explore the context and achievements of the Qajar era, making this the definitive work on ceramics of a fertile time for the applied arts in Persia.

https://www.iamm.org.my/qajar-ceramics- ... modernity/

Qajar Ceramics: Bridging Tradition and Modernity

The Qajar era (1785–1925) was a time of struggle to maintain Persian tradition and identity while embracing innovation and modernity. The rarely explored field of Qajar ceramics typifies the development of the dynasty’s own language and vitality, reflecting the rich vigour of the time. Qajar Ceramics – Bridging Tradition and Modernity is about art in transition, featuring a diversity of ceramic objects from the collection of the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia. Both the publication and the exhibition offer a closer look at the distinctive characteristics of Qajar ceramics, highlighting their forms, aesthetics and themes. Going further, the publication delves into historical sources, revealing newly discovered and important treatises on ceramic artists and kiln technology. Leading authorities have provided essays that explore the context and achievements of the Qajar era, making this the definitive work on ceramics of a fertile time for the applied arts in Persia.

https://www.iamm.org.my/qajar-ceramics- ... modernity/

Great Museums: The Art of Islam at the Met and the Louvre

Today, at a pivotal moment in world history, two great museums beckon us to explore the splendor of Islamic art - lifting the veil on our shared cultural heritage. "Great Museums: The Art of Islam at the Met and the Louvre" showcases the objects on display in the Islamic galleries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and The Louvre in Paris to reveal a roadmap of connections that explains why the foreign seems familiar. Narrated by Philippe de Montebello, the former director of The Met, "Great Museums: The Art of Islam at the Met and the Louvre" examines the extraordinary artistic masterpieces in the museums' Islamic Art collections, and reveals a surprising number of connections that unite Western and Islamic traditions, in art, science, and literature. The film explores the surprising cultural relationships between the Islamic and the Western worlds. The art of Islam reflects 14 centuries of changing political and cultural landscapes across three continents. The term "Islamic art" - coined by 19th century art historians - includes all art produced in Muslim lands from the 7th century forward, from Spain to Morocco, Egypt, the Middle East, Central Asia and India, to the borders of China. Universal museums like The Louvre and The Met help dispel the idea that cultures are exclusive, when, in fact, they are intertwined and connected.

Video at:

https://www.kcet.org/shows/great-museum ... the-art-of

Today, at a pivotal moment in world history, two great museums beckon us to explore the splendor of Islamic art - lifting the veil on our shared cultural heritage. "Great Museums: The Art of Islam at the Met and the Louvre" showcases the objects on display in the Islamic galleries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and The Louvre in Paris to reveal a roadmap of connections that explains why the foreign seems familiar. Narrated by Philippe de Montebello, the former director of The Met, "Great Museums: The Art of Islam at the Met and the Louvre" examines the extraordinary artistic masterpieces in the museums' Islamic Art collections, and reveals a surprising number of connections that unite Western and Islamic traditions, in art, science, and literature. The film explores the surprising cultural relationships between the Islamic and the Western worlds. The art of Islam reflects 14 centuries of changing political and cultural landscapes across three continents. The term "Islamic art" - coined by 19th century art historians - includes all art produced in Muslim lands from the 7th century forward, from Spain to Morocco, Egypt, the Middle East, Central Asia and India, to the borders of China. Universal museums like The Louvre and The Met help dispel the idea that cultures are exclusive, when, in fact, they are intertwined and connected.

Video at:

https://www.kcet.org/shows/great-museum ... the-art-of

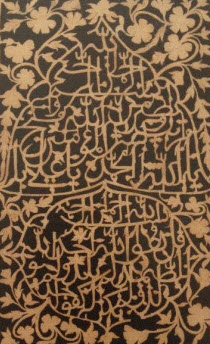

THE ART OF ARABIC CALLIGRAPHY

As part of our Islamic historical and cultural identities around the world, this dying art should be preserved. By Alayna Ahmad.

I have always admired the delicate phrases and words that so artistically adorn the domes of mosques, the courtyard of palaces and the pages of old books. This art form, known as calligraphy, has its roots in ancient Greek, meaning “beautiful writing”.

It has existed for centuries and evolved into various types of scripts. The rich style of Arabic calligraphy was once renowned as the noblest of arts because it directly highlighted the words from the Qur’an. Unfortunately, Arabic calligraphy today is a dying art with few individuals able to master this art form.

With the age of computers, iPhones and tablets, simply writing with a pen has become uncommon for some of us. Nowadays, even greeting cards can be personalized online and shipped straight to the recipient. There is little need to write letters when we have the power of email at our fingertips.

Video and more...

https://www.aquila-style.com/the-art-of ... lligraphy/

As part of our Islamic historical and cultural identities around the world, this dying art should be preserved. By Alayna Ahmad.

I have always admired the delicate phrases and words that so artistically adorn the domes of mosques, the courtyard of palaces and the pages of old books. This art form, known as calligraphy, has its roots in ancient Greek, meaning “beautiful writing”.

It has existed for centuries and evolved into various types of scripts. The rich style of Arabic calligraphy was once renowned as the noblest of arts because it directly highlighted the words from the Qur’an. Unfortunately, Arabic calligraphy today is a dying art with few individuals able to master this art form.

With the age of computers, iPhones and tablets, simply writing with a pen has become uncommon for some of us. Nowadays, even greeting cards can be personalized online and shipped straight to the recipient. There is little need to write letters when we have the power of email at our fingertips.

Video and more...

https://www.aquila-style.com/the-art-of ... lligraphy/

The museum celebrating Greece's link to the Islamic world

We discover artefacts from cities such as Makkah, Cairo and Istanbul during a visit to the Benaki Museum of Islamic Art

It has been a busy two months for Mina Moraitou, head of the Benaki Museum of Islamic Art in Athens. The museum has just finished hosting the Roads of Arabia exhibition straight from Louvre Abu Dhabi and its staff are catching their breath after giving visitors 62 guided tours in only eight weeks.

“It was really a spectacular exhibition,” Moraitou says, speaking in the museum’s sunlit rooftop cafe. “We were able to create scenery to display these objects. So, people were enthusiastic and really interested.”

Moraitou is right to be proud of the museum’s latest achievement. Nestled in a cluster of neoclassical buildings and archaeological sites in the Greek capital’s Kerameikos district, it is one of the few institutions dedicated to Islamic art and culture in Europe.

Video, photos and more...

https://www.thenational.ae/arts-culture ... d-1.872857

Click the link below to learn more about The Benaki Museum of Islamic Art located in historical center of Athens.

https://www.benaki.org/index.php?option ... 36&lang=el

Click link below to take virtual tour of this wonderful Museum.

https://www.benaki.org/virtual/islamiki ... ml?lang=el

We discover artefacts from cities such as Makkah, Cairo and Istanbul during a visit to the Benaki Museum of Islamic Art