Picture in Places of Worship

Picture in Places of Worship

Hi All,

I have some questions on some of our practices in which one of them is worshiping pictures. I have seen many people reciting salwat on the picture of imam, or talking to the picture or bowing down to the picture. Why do we do it.

In Islam its considered shirk if someone prays to a statue or a picture as they both are man made. I remember reading in a ginan I guess it was 100 good things, not to worship physical things, even in ginan Putla by sat gur noor, He says if these things are man made how can it solve your problems.

If its a bad thing to do, why doesnt Hazir Imam says anything as He is our guide.

Thanks

I have some questions on some of our practices in which one of them is worshiping pictures. I have seen many people reciting salwat on the picture of imam, or talking to the picture or bowing down to the picture. Why do we do it.

In Islam its considered shirk if someone prays to a statue or a picture as they both are man made. I remember reading in a ginan I guess it was 100 good things, not to worship physical things, even in ginan Putla by sat gur noor, He says if these things are man made how can it solve your problems.

If its a bad thing to do, why doesnt Hazir Imam says anything as He is our guide.

Thanks

Nothing bad. people even kiss the photo of their loved ones. So what?

Do you really think they kiss a piece of paper or is it that they kiss the one the photo reminds them of? Isn't that recognised by the whole world minus some brainwashed Mullas as a sign of affection and love?

Why indulge in cheap shariati propaganda?

Do you really think they kiss a piece of paper or is it that they kiss the one the photo reminds them of? Isn't that recognised by the whole world minus some brainwashed Mullas as a sign of affection and love?

Why indulge in cheap shariati propaganda?

To show affection sure but why recite salwat or pray in front of it. Ismailism teaches us to care about spiritual aspect of noor not physical which is mortal.

Noor is considered to be everywhere and when someone goes to pray place that is already house of God then why go to a picture hanging on a wall and praying, I dont think God would be sitting just there.

Since long humans are in a habit of creating something physical to remind them of something in this case God. Moses had to come back to his people because they created a statue and started worshiping it. God got angry and told Moses to go back to his people.

I am not concerned of mullah doing something bad, this is just for me and if someone wants answers based on this thing.

Noor is considered to be everywhere and when someone goes to pray place that is already house of God then why go to a picture hanging on a wall and praying, I dont think God would be sitting just there.

Since long humans are in a habit of creating something physical to remind them of something in this case God. Moses had to come back to his people because they created a statue and started worshiping it. God got angry and told Moses to go back to his people.

I am not concerned of mullah doing something bad, this is just for me and if someone wants answers based on this thing.

There is nothing wrong in human being worshiping in front of symbols of faith as far as they do not worship those symboles themselves such as Kaba, idols, dargah, cross etc..

even God needed a name such as Allah, he needed attributes in order to be known and worshiped.

A name is a physical limited word. An attribute is a limitation to Allah. Allah can not be limited by an attribute because God is supposed to be beyond attributes Yet we call him Ar Rahman, Ar Rahim, Al Khaliq and God does not have any objection on that so why would anyone have objection to people's variety of ways of approaching God?

Faith is a personal matter between God and his creation and no one can dare come in between a person and God.

Even Prophet Moses (Moosa Nabi) needed the burning bush, he who was a prophet could not see God without some kind of support and some kind of physical symbol!

And the fact that people get more benefit in praying in a place of worship though Allah is everywhere shown that physical symbols are important.

even God needed a name such as Allah, he needed attributes in order to be known and worshiped.

A name is a physical limited word. An attribute is a limitation to Allah. Allah can not be limited by an attribute because God is supposed to be beyond attributes Yet we call him Ar Rahman, Ar Rahim, Al Khaliq and God does not have any objection on that so why would anyone have objection to people's variety of ways of approaching God?

Faith is a personal matter between God and his creation and no one can dare come in between a person and God.

Even Prophet Moses (Moosa Nabi) needed the burning bush, he who was a prophet could not see God without some kind of support and some kind of physical symbol!

And the fact that people get more benefit in praying in a place of worship though Allah is everywhere shown that physical symbols are important.

I am just quoting one surah from Quran:

You only worship, besides Allah , idols, and you produce a falsehood. Indeed, those you worship besides Allah do not possess for you [the power of] provision. So seek from Allah provision and worship Him and be grateful to Him. To Him you will be returned."

worshiping in front does cause them to worship that object, as they tend to ask help from that object rather than God himself.

Prophet Moses never worshiped that bush, He didn't even know that God will use this bush to show him a sign of His existence.

We use pictures, dhagas around necks etc and seek help from an object, base on that object that wearing this would help me out of danger. Why not think something like Mola is with me all the time, He will save me from all troubles.

When Prophet Muhammad was reciting Salah, He got revelation from God that all the people in front of you is actually bowing down to their statues located inside their long sleeves and got a command to make them all stand and all of those statues started to fall down from their sleeves.

I am not coming in between anyone's faith, I am looking for answers for myself.

You only worship, besides Allah , idols, and you produce a falsehood. Indeed, those you worship besides Allah do not possess for you [the power of] provision. So seek from Allah provision and worship Him and be grateful to Him. To Him you will be returned."

worshiping in front does cause them to worship that object, as they tend to ask help from that object rather than God himself.

Prophet Moses never worshiped that bush, He didn't even know that God will use this bush to show him a sign of His existence.

We use pictures, dhagas around necks etc and seek help from an object, base on that object that wearing this would help me out of danger. Why not think something like Mola is with me all the time, He will save me from all troubles.

When Prophet Muhammad was reciting Salah, He got revelation from God that all the people in front of you is actually bowing down to their statues located inside their long sleeves and got a command to make them all stand and all of those statues started to fall down from their sleeves.

I am not coming in between anyone's faith, I am looking for answers for myself.

You will find your answer when you stop imaginary belief such as "worshiping in front does cause them to worship that object" and when you start accepting that when it comes to people believing in Allah, only Allah can judge.

And while you are looking for answers for yourself, take peace in knowing that what other believe is their own problem to resolve with their own Allah, not yours.

And while you are looking for answers for yourself, take peace in knowing that what other believe is their own problem to resolve with their own Allah, not yours.

I am not saying what others are doing is bad its what human does create something physical to keep their heart contended.

My question is more towards is it a ismailism practice is there any reference, what you are telling me is your belief not an answer you are giving me a statement that i shouldnt question further.

Do you have any reference that if someone does like that its considered a good practice in ismailism

Christian kisses cross symbol, muslims have tasbeeh that we kiss i knw all that already.

Ismailism is already a belief where our pir and imam guides us towards a uniform ismaili belief but as human we do add alot thats what my question is.

My question is more towards is it a ismailism practice is there any reference, what you are telling me is your belief not an answer you are giving me a statement that i shouldnt question further.

Do you have any reference that if someone does like that its considered a good practice in ismailism

Christian kisses cross symbol, muslims have tasbeeh that we kiss i knw all that already.

Ismailism is already a belief where our pir and imam guides us towards a uniform ismaili belief but as human we do add alot thats what my question is.

If there were photographs during the time of the Prophet, I am sure we would have had photographs of the Prophet in all Muslim homes.

Below is an excerpt of an article on the importance of the image of Muhammad.

"Regarding images: Muhammad is a powerful symbol for Muslims. The Quran calls him a “beautiful role model,” and he is considered to be the most perfect Muslim.

It is generally accepted by Muslims that images of Muhammad, or any other person, do not appear in mosques.

However, this ban does not extend outside the mosque. Various Muslim cultures show a comfort with painting and figural representation. Images of Muhammad, his family, prophets and other holy figures exist. They are on display in museums throughout the world. In some, the faces are obscured, but in many, the faces are on full display.

While more common among Shiite communities, some of the most well-known depictions of Muhammad come from Sunni Turkey. In nonliturgical spaces, images of holy figures abound, including Muhammad.

The tradition of representation is very much alive throughout the Muslim communities, and books such as Sufi Comics demonstrate a desire for learning through the image.

Still, there is a strong belief that any depiction of Muhammad is a problem. In part, this is due to a lack of religious literacy, and in part to a puritanical, nihilistic vision of Islam supported by Saudi Arabia.

The result is that Muhammad is actually turned into an idol. He is turned into the God, which Muslims do not believe can be depicted at all."

http://www.washingtonpost.com/national/ ... story.html

"Yes, many Muslims today do not approve of images depicting the Prophet, or for that matter depicting Christ or Moses (also venerated as prophets by Muslims). But this was not and is not the case for all Muslims. Muslims in South Asia, Iran, Turkey and Central Asia — places that were for centuries the centers of Muslim civilizations — had a rich tradition of miniatures that depicted all the prophets, including those depicting the Prophet Muhammad. These were not rogue images, done in secret, but rather an elite art paid for and patronized by the Muslim caliphs and sultans, produced in the courts of the Muslims."

http://www.onbeing.org/blog/9-points-to ... hebdo/7193

Below is an excerpt of an article on the importance of the image of Muhammad.

"Regarding images: Muhammad is a powerful symbol for Muslims. The Quran calls him a “beautiful role model,” and he is considered to be the most perfect Muslim.

It is generally accepted by Muslims that images of Muhammad, or any other person, do not appear in mosques.

However, this ban does not extend outside the mosque. Various Muslim cultures show a comfort with painting and figural representation. Images of Muhammad, his family, prophets and other holy figures exist. They are on display in museums throughout the world. In some, the faces are obscured, but in many, the faces are on full display.

While more common among Shiite communities, some of the most well-known depictions of Muhammad come from Sunni Turkey. In nonliturgical spaces, images of holy figures abound, including Muhammad.

The tradition of representation is very much alive throughout the Muslim communities, and books such as Sufi Comics demonstrate a desire for learning through the image.

Still, there is a strong belief that any depiction of Muhammad is a problem. In part, this is due to a lack of religious literacy, and in part to a puritanical, nihilistic vision of Islam supported by Saudi Arabia.

The result is that Muhammad is actually turned into an idol. He is turned into the God, which Muslims do not believe can be depicted at all."

http://www.washingtonpost.com/national/ ... story.html

"Yes, many Muslims today do not approve of images depicting the Prophet, or for that matter depicting Christ or Moses (also venerated as prophets by Muslims). But this was not and is not the case for all Muslims. Muslims in South Asia, Iran, Turkey and Central Asia — places that were for centuries the centers of Muslim civilizations — had a rich tradition of miniatures that depicted all the prophets, including those depicting the Prophet Muhammad. These were not rogue images, done in secret, but rather an elite art paid for and patronized by the Muslim caliphs and sultans, produced in the courts of the Muslims."

http://www.onbeing.org/blog/9-points-to ... hebdo/7193

What about the hair of Prophet Mohd!!!? In one place in Kashmir ( Indian occupied) people says that they have hair of prophet Mohd!!!The Prophet's shirt is also on display at that museum.

Now question may arise here, how the hair reach over there? did Rasoolullah visited that place? these questions are still unanswered!

Does Islam Really Forbid Images Of Muhammad?

Muslims the world over have strongly condemned Wednesday’s terrorist attack against the French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo, in which 12 people were killed by masked gunmen. The paper is believed to have been targeted because of its history of publishing provocative cartoons depicting the Prophet Muhammad. But what do the teachings of Islam actually say about creating images of the prophet?

There's no part in the Quran where Muhammad says that images of him are forbidden. But the issue is mentioned in the hadith, a secondary text that many Muslims consult for instruction on how to live a good life.

More....

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/01/0 ... 32370.html

Muslims the world over have strongly condemned Wednesday’s terrorist attack against the French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo, in which 12 people were killed by masked gunmen. The paper is believed to have been targeted because of its history of publishing provocative cartoons depicting the Prophet Muhammad. But what do the teachings of Islam actually say about creating images of the prophet?

There's no part in the Quran where Muhammad says that images of him are forbidden. But the issue is mentioned in the hadith, a secondary text that many Muslims consult for instruction on how to live a good life.

More....

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/01/0 ... 32370.html

There is difference hereAdmin wrote:The subject has been discussed in another thread. Please stick to the thread here.junglikhan4 wrote: An innocent question; does the photos hanging R/L sides of wall in JK are divine. I have seen persons praying in front of them, prostrate in front of them,

kissing the photo and frame. Are we noor parast or photo parast.

KIYA YEH KHULA TAZADD NAHI HAI!

To give you a short analogy, When I travel, whenever I miss my daughter I kiss my daughter's photo. You may think I am crazy to kiss a piece of paper but for me the photo reminds me of my daughter. I can see beyond the paper. Not everyone can. Especially those who do not have any kind of father-daughter relation with her would not understand. People whi kiss Imam's photo, in Jk or at home like some kids in my family do, can see beyond the frame....

Only God can give you the sight to see him and when he does, he becomes your eye

You kiss your daughters picture because you love her and miss her

Kissing photo of Imam is different. With love there is element of worship.

Who do you worship, God or Imam?

Or you are worshipping God by worshipping Imam.

In Islam there is no image of Allah.

Please do not bring in Kaaba.

zznoor, your point is taken (and ignored)

Your reasoning is completely flawed and Kaba question is the reply to your lack of reasoning.

I love my Imam as much if not more than I love my daughter and it is not to you to judge how I express love for both of them.

If you do so, you are no different than ISIS and all the terrorists that want to impose to us, the 1.2 billion Muslims, their own version of a completely screwed-up Islam which has nothing to do with the real Islam.

You have been repeating yourself and I would like you to first read the previous discussions before posting anything. Thanks you.

Your reasoning is completely flawed and Kaba question is the reply to your lack of reasoning.

I love my Imam as much if not more than I love my daughter and it is not to you to judge how I express love for both of them.

If you do so, you are no different than ISIS and all the terrorists that want to impose to us, the 1.2 billion Muslims, their own version of a completely screwed-up Islam which has nothing to do with the real Islam.

You have been repeating yourself and I would like you to first read the previous discussions before posting anything. Thanks you.

Last edited by Admin on Fri Jul 17, 2015 1:09 am, edited 1 time in total.

You were previously directed to the discussion on this subject. Please go through the thread below.zznoor wrote: Who do you worship, God or Imam?

Or you are worshipping God by worshipping Imam.

Allah and the Nur of Allah

http://www.ismaili.net/html/modules.php ... 01&start=0

Love and devotion to the Imam is the essence of Ismailism. Below are some pertinent Farmans.

"Without the intent and the love for Hazar Imam nothing is accepted. This is established from the

Qur'an and the Hadiths. No Ibadat - Bandagi is accepted without the love and affection for the Prophet and progeny of the Prophet, who is the successor to the Gadi (Throne)." (Bombay 8 September 1885)

"Just as you see us physically, in the same way consider us to be ever-present and remember us while sitting, standing and walking. Your love and affection is always in our hearts and (prayers)." (Zanzibar Aug 18, 1905)

"There is nothing greater than to have love and affection for your Present - Living Imam. Always be immersed in the love of the Imam." (Dar es Salaam Feb 15, 1937)

"It is obligatory for a momin to cultivate love and affection for his Imam in his heart." ( Guaadar Dec 10, 1894)

When the Ismaili Centre London was built, it had 2 beautiful artistic portraits of MHI at the front as portent symbols of love and devotion to the Living Imam.

In my opinion we should have at least 1 photograph in the front during the Tariqah practices which may be removed after the ceremonies are over. This will serve as an important doctrinal reminder that all our rites and ceremonies are predicated upon the love and devotion to the Living Imam.

"Without the intent and the love for Hazar Imam nothing is accepted. This is established from the

Qur'an and the Hadiths. No Ibadat - Bandagi is accepted without the love and affection for the Prophet and progeny of the Prophet, who is the successor to the Gadi (Throne)." (Bombay 8 September 1885)

"Just as you see us physically, in the same way consider us to be ever-present and remember us while sitting, standing and walking. Your love and affection is always in our hearts and (prayers)." (Zanzibar Aug 18, 1905)

"There is nothing greater than to have love and affection for your Present - Living Imam. Always be immersed in the love of the Imam." (Dar es Salaam Feb 15, 1937)

"It is obligatory for a momin to cultivate love and affection for his Imam in his heart." ( Guaadar Dec 10, 1894)

When the Ismaili Centre London was built, it had 2 beautiful artistic portraits of MHI at the front as portent symbols of love and devotion to the Living Imam.

In my opinion we should have at least 1 photograph in the front during the Tariqah practices which may be removed after the ceremonies are over. This will serve as an important doctrinal reminder that all our rites and ceremonies are predicated upon the love and devotion to the Living Imam.

Review Essays

Journal of Persianate Studies

Aliaa Remtilla, Potentially an “Art Object”: Tajik Ismailis’ Bateni and Zaheri Engagement with Their Imam’s Image

This essay explores the way Ismaili Muslims living in the Tajik district of Ishkashim engage with images of their religious leader, the Imam (Aga Khan IV). I use Gell’s theory of art and agency to think through instances in which Ishkashimis imbue photographs of their Imam with the capacity

to act. They do not treat these images as idols but abduct qualities of the Imam himself, such as his benevolent presence, from his icon. Ishkashimis do not imbue all images of their Imam with agency. Other images, such as newspaper photographs and films, provide information about the Imam as a politically engaged individual. They do not have the agency to act directly on Ishkashimis until and unless Ishkashimis reclaim their own agenda for the Imam’s image by abstracting it from contextualized information, and once more imbue it with agency. The article frames this discussion of images in the Ismaili concepts of zaher (visible, apparent, temporal, transient, exoteric) and baten (interior, hidden, spiritual, eternal, esoteric), questioning the effect of the Imam’s post-Soviet zaheri presence on Ishkashimis’ engagement with his images.

http://www.brill.com/sites/default/file ... ochure.pdf

Journal of Persianate Studies

Aliaa Remtilla, Potentially an “Art Object”: Tajik Ismailis’ Bateni and Zaheri Engagement with Their Imam’s Image

This essay explores the way Ismaili Muslims living in the Tajik district of Ishkashim engage with images of their religious leader, the Imam (Aga Khan IV). I use Gell’s theory of art and agency to think through instances in which Ishkashimis imbue photographs of their Imam with the capacity

to act. They do not treat these images as idols but abduct qualities of the Imam himself, such as his benevolent presence, from his icon. Ishkashimis do not imbue all images of their Imam with agency. Other images, such as newspaper photographs and films, provide information about the Imam as a politically engaged individual. They do not have the agency to act directly on Ishkashimis until and unless Ishkashimis reclaim their own agenda for the Imam’s image by abstracting it from contextualized information, and once more imbue it with agency. The article frames this discussion of images in the Ismaili concepts of zaher (visible, apparent, temporal, transient, exoteric) and baten (interior, hidden, spiritual, eternal, esoteric), questioning the effect of the Imam’s post-Soviet zaheri presence on Ishkashimis’ engagement with his images.

http://www.brill.com/sites/default/file ... ochure.pdf

And what would that divine image look like?Yes if we introduce Namaz in JKs, it will overflow five times a day. Is that the purpose of our Tariqa?mazharshah wrote: Sir, instead of physical photos of Imam in JK's, why not ITREB arrange divine image that is real photo of NOOR in front that will increase the attendance of JK. LOVE AND RESPECT IS IN HEART AND SOUL..

Photograph of the prsent Imam serves as a powerful reminder of the fundamentals of our tradition. That he is the Mazhar or Hujjat through whom Allah is worshipped and obeyed.mazharshah wrote:Regarding smile Hazar Imam said," It is blessing from Allah"

In mostly JK's there are photos of Imam when he was young, now he is aging 78 years old. Do you think 50 years back Noor was young now aging.

We should have feeling of Noor every second and it has nothing to do with photos. Photo of Shah Karim is different than photo of MSMS and photo of Shah Ali Shah was different than photo of MSMS.

Yes the image of the Imam will change from Imam to Imam. The photograph of the present Imam reminds us of our collective identity which is predicated upon love and devotion to the Living Imam.

Due to busy nature of life and the saturation of our minds with material aspects, we can forget about our faith. A photograph can serve as a powerful reminder of our purpose in life and our fundamental values.

-

shivaathervedi_3

- Posts: 354

- Joined: Wed May 16, 2018 7:29 pm

TASWEER TERI DIL MERA BAHLA NA SAKEY GI

MAI(N) BAAT KARU(N) GA WOH KHAMOSH RAHEY GI

NA SUN SAKEY GI NA JAWAB HI DEY SAKEY GI

MAI(N) HAATH LAGAU(N) TOU WOH KUCHH NA KAHEY GI

NA SHARMAI GI MUJHEY DEKH KAR NA GHU(N)GHAT GRAI GI

NOOR KI TASWEER NA PAHLEY THI NA ABB HAI NA HOGI

YAADUN KI BARAAT DIL MEY YA KHAYALU(N) MEY HOGI

NOOR KA PANA DEKHNA ZINDAGI MEY MUMKIN NAHI

ZAHIR DEKH KHUSH RAHO YEH ZINDZGI KI KAMAI HOGI

MAI(N) BAAT KARU(N) GA WOH KHAMOSH RAHEY GI

NA SUN SAKEY GI NA JAWAB HI DEY SAKEY GI

MAI(N) HAATH LAGAU(N) TOU WOH KUCHH NA KAHEY GI

NA SHARMAI GI MUJHEY DEKH KAR NA GHU(N)GHAT GRAI GI

NOOR KI TASWEER NA PAHLEY THI NA ABB HAI NA HOGI

YAADUN KI BARAAT DIL MEY YA KHAYALU(N) MEY HOGI

NOOR KA PANA DEKHNA ZINDAGI MEY MUMKIN NAHI

ZAHIR DEKH KHUSH RAHO YEH ZINDZGI KI KAMAI HOGI

-

swamidada_2

- Posts: 297

- Joined: Mon Aug 19, 2019 8:18 pm

Images

Ertugrul gets a statue in Lahore

PUBLISHED ABOUT 18 HOURS AGO

XARI JALIL

NEWSPAPER REPORTER

At present, there are two statues that depict Ertugrul on a horse, the second will be called Ertugrul Ghazi Chowk.

The community members of an area in Lahore are so smitten by the Turkish television series, based on the character of Ertugrul, that they have paid a tribute to him by erecting a statue in their neighbourhood.

The TV series, Ertugrul Ghazi, originally Dirilis: Ertugrul in Turkish is being aired on the Pakistan Television in Urdu language and has been endorsed by Prime Minister Imran Khan himself.

The warrior in the statue in the Maraghzar Housing Scheme situated along the Multan Road is seen carrying a sword and riding a horse.

Muhammad Shahzad Cheema, the president of the Maraghzar Housing Scheme, says he decided to erect the statues of Ertugrul after some of the residents floated the idea of paying a tribute to him. Giving details of the project, he says these special statues have been made using fibre and metal in the city of Kamalia of Toba Tek Singh district.

“I won’t mention the cost of these statues; otherwise, their value would get the attention of the public,” Cheema laughs. “I went to Kamalia myself to place the order for these statues.”

At present, there are two statues that depict Ertugrul on a horse. One of them has been unveiled while the other is going to be erected soon possibly at a central place.

“We will call the place Ertugrul Ghazi Chowk,” says Sohail Anwar Rana, the secretary general of the scheme, referring to the location where the first statue has been unveiled.

Cheema says that while the entire country was enjoying the TV series and got acquainted with the historical figure after watching the show, he already knew about him. “I had read about him beforehand,” asserts Cheema.

“What has affected me most about this character is the way he united the entire tribe and formed the Ottoman Empire – this is something that the world’s anti-Muslim community cannot digest. Our kids may enjoy the show, but they should be able to also see him in artistic depiction – something physical they can marvel at”.

Who is Ertugrul?

Not much is known about Ertugrul from 13th century as there is a lack of authentic information about him. Even name of his father comes in two different versions, Suleyman Shah and Gunduz Alp. What is authentically known about him is that he was father of Osman I, the founder of Ottoman Empire. Most of information about him comes from the stories about him written during the Ottoman Empire about a century later.

Pervaiz Hoodbhoy in his column in this newspaper has quoted Mehmet Bozdag, thewriter and producer of the TV series, saying, “Facts are not important. There is very little information about the period we are presenting — not exceeding 4-5 pages. Even the names are different in every source. The first works written about the establishment of the Ottoman State were about 100-150 years later. There is no certainty in this historical data… we are shaping a story by dreaming”.

When asked about the accurate depiction of Ertugrul, Cheema does not give it much importance, saying that it does not matter because writers tend to take liberty through artistic licence, especially in TV programmes and movies. But what should be kept in mind is that under the Ottoman Empire, more than 30 countries were united – something that is a food for thought for the Muslims today, he says.

Reaction to Statue

Ever since the unveiling of the statue, it has become a centre of attention of the people who have started gathering around hit to stand and stare at it or even to take selfies with it. But not all historical figures are seen in the same way, especially by those who revere Ertugrul.

A similar statue of Sikh Emperor Maharaja Ranjit Singh, who founded the Punjab Empire and ruled parts of, what is now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, was unveiled last year in the Lahore Fort.

However, just a few days after its unveiling, it was vandalised by members of an extremist religious organisation.

The people like Cheema though have a different perspective.

“As Muslims we should not give regard to Ranjit Singh as his rule led to antagonism against the Muslims,” he says, waiving aside the fact that the emperor, who hailed from Gujranwala, was one of the most important in the history of the land.

*Originally published in Dawn, June 7th, 2020**

https://images.dawn.com/news/1185375/er ... -in-lahore

Ertugrul gets a statue in Lahore

PUBLISHED ABOUT 18 HOURS AGO

XARI JALIL

NEWSPAPER REPORTER

At present, there are two statues that depict Ertugrul on a horse, the second will be called Ertugrul Ghazi Chowk.

The community members of an area in Lahore are so smitten by the Turkish television series, based on the character of Ertugrul, that they have paid a tribute to him by erecting a statue in their neighbourhood.

The TV series, Ertugrul Ghazi, originally Dirilis: Ertugrul in Turkish is being aired on the Pakistan Television in Urdu language and has been endorsed by Prime Minister Imran Khan himself.

The warrior in the statue in the Maraghzar Housing Scheme situated along the Multan Road is seen carrying a sword and riding a horse.

Muhammad Shahzad Cheema, the president of the Maraghzar Housing Scheme, says he decided to erect the statues of Ertugrul after some of the residents floated the idea of paying a tribute to him. Giving details of the project, he says these special statues have been made using fibre and metal in the city of Kamalia of Toba Tek Singh district.

“I won’t mention the cost of these statues; otherwise, their value would get the attention of the public,” Cheema laughs. “I went to Kamalia myself to place the order for these statues.”

At present, there are two statues that depict Ertugrul on a horse. One of them has been unveiled while the other is going to be erected soon possibly at a central place.

“We will call the place Ertugrul Ghazi Chowk,” says Sohail Anwar Rana, the secretary general of the scheme, referring to the location where the first statue has been unveiled.

Cheema says that while the entire country was enjoying the TV series and got acquainted with the historical figure after watching the show, he already knew about him. “I had read about him beforehand,” asserts Cheema.

“What has affected me most about this character is the way he united the entire tribe and formed the Ottoman Empire – this is something that the world’s anti-Muslim community cannot digest. Our kids may enjoy the show, but they should be able to also see him in artistic depiction – something physical they can marvel at”.

Who is Ertugrul?

Not much is known about Ertugrul from 13th century as there is a lack of authentic information about him. Even name of his father comes in two different versions, Suleyman Shah and Gunduz Alp. What is authentically known about him is that he was father of Osman I, the founder of Ottoman Empire. Most of information about him comes from the stories about him written during the Ottoman Empire about a century later.

Pervaiz Hoodbhoy in his column in this newspaper has quoted Mehmet Bozdag, thewriter and producer of the TV series, saying, “Facts are not important. There is very little information about the period we are presenting — not exceeding 4-5 pages. Even the names are different in every source. The first works written about the establishment of the Ottoman State were about 100-150 years later. There is no certainty in this historical data… we are shaping a story by dreaming”.

When asked about the accurate depiction of Ertugrul, Cheema does not give it much importance, saying that it does not matter because writers tend to take liberty through artistic licence, especially in TV programmes and movies. But what should be kept in mind is that under the Ottoman Empire, more than 30 countries were united – something that is a food for thought for the Muslims today, he says.

Reaction to Statue

Ever since the unveiling of the statue, it has become a centre of attention of the people who have started gathering around hit to stand and stare at it or even to take selfies with it. But not all historical figures are seen in the same way, especially by those who revere Ertugrul.

A similar statue of Sikh Emperor Maharaja Ranjit Singh, who founded the Punjab Empire and ruled parts of, what is now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, was unveiled last year in the Lahore Fort.

However, just a few days after its unveiling, it was vandalised by members of an extremist religious organisation.

The people like Cheema though have a different perspective.

“As Muslims we should not give regard to Ranjit Singh as his rule led to antagonism against the Muslims,” he says, waiving aside the fact that the emperor, who hailed from Gujranwala, was one of the most important in the history of the land.

*Originally published in Dawn, June 7th, 2020**

https://images.dawn.com/news/1185375/er ... -in-lahore

Below is the description of the impact of a photograph of a master upon a devoted disciple in the Autobiography of a Yogi at:

https://www.ananda.org/autobiography/#chap1

Lahiri Mahasaya left this world shortly after I had entered it. His picture, in an ornate frame, always graced our family altar in the various cities to which Father was transferred by his office. Many a morning and evening found Mother and me meditating before an improvised shrine, offering flowers dipped in fragrant sandalwood paste. With frankincense and myrrh as well as our united devotions, we honored the divinity which had found full expression in Lahiri Mahasaya.

His picture had a surpassing influence over my life. As I grew, the thought of the master grew with me. In meditation I would often see his photographic image emerge from its small frame and, taking a living form, sit before me. When I attempted to touch the feet of his luminous body, it would change and again become the picture. As childhood slipped into boyhood, I found Lahiri Mahasaya transformed in my mind from a little image, cribbed in a frame, to a living, enlightening presence. I frequently prayed to him in moments of trial or confusion, finding within me his solacing direction. At first I grieved because he was no longer physically living. As I began to discover his secret omnipresence, I lamented no more. He had often written to those of his disciples who were over-anxious to see him: “Why come to view my bones and flesh, when I am ever within range of your kutastha (spiritual sight)?”

I was blessed about the age of eight with a wonderful healing through the photograph of Lahiri Mahasaya. This experience gave intensification to my love. While at our family estate in Ichapur, Bengal, I was stricken with Asiatic cholera. My life was despaired of; the doctors could do nothing. At my bedside, Mother frantically motioned me to look at Lahiri Mahasaya’s picture on the wall above my head.

“Bow to him mentally!” She knew I was too feeble even to lift my hands in salutation. “If you really show your devotion and inwardly kneel before him, your life will be spared!”

I gazed at his photograph and saw there a blinding light, enveloping my body and the entire room. My nausea and other uncontrollable symptoms disappeared; I was well. At once I felt strong enough to bend over and touch Mother’s feet in appreciation of her immeasurable faith in her guru. Mother pressed her head repeatedly against the little picture.

“O Omnipresent Master, I thank thee that thy light hath healed my son!”

I realized that she too had witnessed the luminous blaze through which I had instantly recovered from a usually fatal disease.

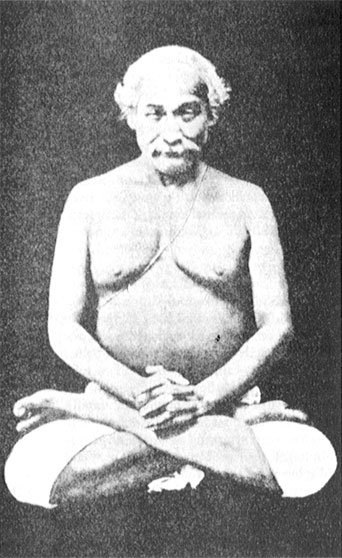

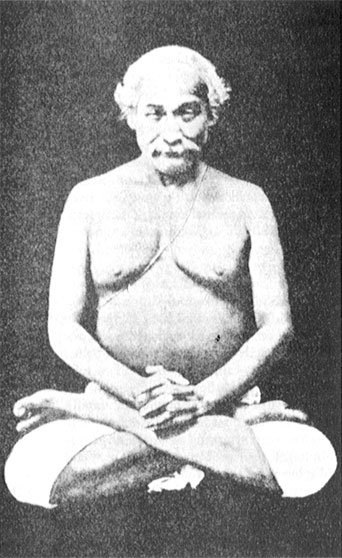

One of my most precious possessions is that same photograph. Given to Father by Lahiri Mahasaya himself, it carries a holy vibration. The picture had a miraculous origin. I heard the story from Father’s brother disciple, Kali Kumar Roy.

It appears that the master had an aversion to being photographed. Over his protest, a group picture was once taken of him and a cluster of devotees, including Kali Kumar Roy. It was an amazed photographer who discovered that the plate which had clear images of all the disciples, revealed nothing more than a blank space in the center where he had reasonably expected to find the outlines of Lahiri Mahasaya. The phenomenon was widely discussed.

A certain student and expert photographer, Ganga Dhar Babu, boasted that the fugitive figure would not escape him. The next morning, as the guru sat in lotus posture on a wooden bench with a screen behind him, Ganga Dhar Babu arrived with his equipment. Taking every precaution for success, he greedily exposed twelve plates. On each one he soon found the imprint of the wooden bench and screen, but once again the master’s form was missing.

With tears and shattered pride, Ganga Dhar Babu sought out his guru. It was many hours before Lahiri Mahasaya broke his silence with a pregnant comment:

“I am Spirit. Can your camera reflect the omnipresent Invisible?”

“I see it cannot! But, Holy Sir, I lovingly desire a picture of the bodily temple where alone, to my narrow vision, that Spirit appears fully to dwell.”

“Come, then, tomorrow morning. I will pose for you.”

Again the photographer focused his camera. This time the sacred figure, not cloaked with mysterious imperceptibility, was sharp on the plate. The master never posed for another picture; at least, I have seen none.

The photograph is reproduced in this book. Lahiri Mahasaya’s fair features, of a universal cast, hardly suggest to what race he belonged. His intense joy of God-communion is slightly revealed in a somewhat enigmatic smile. His eyes, half open to denote a nominal direction on the outer world, are half closed also. Completely oblivious to the poor lures of the earth, he was fully awake at all times to the spiritual problems of seekers who approached for his bounty.

Shortly after my healing through the potency of the guru’s picture, I had an influential spiritual vision. Sitting on my bed one morning, I fell into a deep reverie.

“What is behind the darkness of closed eyes?” This probing thought came powerfully into my mind. An immense flash of light at once manifested to my inward gaze. Divine shapes of saints, sitting in meditation posture in mountain caves, formed like miniature cinema pictures on the large screen of radiance within my forehead.

“Who are you?” I spoke aloud.

“We are the Himalayan yogis.” The celestial response is difficult to describe; my heart was thrilled.

“Ah, I long to go to the Himalayas and become like you!” The vision vanished, but the silvery beams expanded in ever-widening circles to infinity.

“What is this wondrous glow?”

“I am Iswara.10 I am Light.” The voice was as murmuring clouds.

“I want to be one with Thee!”

Out of the slow dwindling of my divine ecstasy, I salvaged a permanent legacy of inspiration to seek God. “He is eternal, ever-new Joy!” This memory persisted long after the day of rapture.

https://www.ananda.org/autobiography/#chap1

Lahiri Mahasaya left this world shortly after I had entered it. His picture, in an ornate frame, always graced our family altar in the various cities to which Father was transferred by his office. Many a morning and evening found Mother and me meditating before an improvised shrine, offering flowers dipped in fragrant sandalwood paste. With frankincense and myrrh as well as our united devotions, we honored the divinity which had found full expression in Lahiri Mahasaya.

His picture had a surpassing influence over my life. As I grew, the thought of the master grew with me. In meditation I would often see his photographic image emerge from its small frame and, taking a living form, sit before me. When I attempted to touch the feet of his luminous body, it would change and again become the picture. As childhood slipped into boyhood, I found Lahiri Mahasaya transformed in my mind from a little image, cribbed in a frame, to a living, enlightening presence. I frequently prayed to him in moments of trial or confusion, finding within me his solacing direction. At first I grieved because he was no longer physically living. As I began to discover his secret omnipresence, I lamented no more. He had often written to those of his disciples who were over-anxious to see him: “Why come to view my bones and flesh, when I am ever within range of your kutastha (spiritual sight)?”

I was blessed about the age of eight with a wonderful healing through the photograph of Lahiri Mahasaya. This experience gave intensification to my love. While at our family estate in Ichapur, Bengal, I was stricken with Asiatic cholera. My life was despaired of; the doctors could do nothing. At my bedside, Mother frantically motioned me to look at Lahiri Mahasaya’s picture on the wall above my head.

“Bow to him mentally!” She knew I was too feeble even to lift my hands in salutation. “If you really show your devotion and inwardly kneel before him, your life will be spared!”

I gazed at his photograph and saw there a blinding light, enveloping my body and the entire room. My nausea and other uncontrollable symptoms disappeared; I was well. At once I felt strong enough to bend over and touch Mother’s feet in appreciation of her immeasurable faith in her guru. Mother pressed her head repeatedly against the little picture.

“O Omnipresent Master, I thank thee that thy light hath healed my son!”

I realized that she too had witnessed the luminous blaze through which I had instantly recovered from a usually fatal disease.

One of my most precious possessions is that same photograph. Given to Father by Lahiri Mahasaya himself, it carries a holy vibration. The picture had a miraculous origin. I heard the story from Father’s brother disciple, Kali Kumar Roy.

It appears that the master had an aversion to being photographed. Over his protest, a group picture was once taken of him and a cluster of devotees, including Kali Kumar Roy. It was an amazed photographer who discovered that the plate which had clear images of all the disciples, revealed nothing more than a blank space in the center where he had reasonably expected to find the outlines of Lahiri Mahasaya. The phenomenon was widely discussed.

A certain student and expert photographer, Ganga Dhar Babu, boasted that the fugitive figure would not escape him. The next morning, as the guru sat in lotus posture on a wooden bench with a screen behind him, Ganga Dhar Babu arrived with his equipment. Taking every precaution for success, he greedily exposed twelve plates. On each one he soon found the imprint of the wooden bench and screen, but once again the master’s form was missing.

With tears and shattered pride, Ganga Dhar Babu sought out his guru. It was many hours before Lahiri Mahasaya broke his silence with a pregnant comment:

“I am Spirit. Can your camera reflect the omnipresent Invisible?”

“I see it cannot! But, Holy Sir, I lovingly desire a picture of the bodily temple where alone, to my narrow vision, that Spirit appears fully to dwell.”

“Come, then, tomorrow morning. I will pose for you.”

Again the photographer focused his camera. This time the sacred figure, not cloaked with mysterious imperceptibility, was sharp on the plate. The master never posed for another picture; at least, I have seen none.

The photograph is reproduced in this book. Lahiri Mahasaya’s fair features, of a universal cast, hardly suggest to what race he belonged. His intense joy of God-communion is slightly revealed in a somewhat enigmatic smile. His eyes, half open to denote a nominal direction on the outer world, are half closed also. Completely oblivious to the poor lures of the earth, he was fully awake at all times to the spiritual problems of seekers who approached for his bounty.

Shortly after my healing through the potency of the guru’s picture, I had an influential spiritual vision. Sitting on my bed one morning, I fell into a deep reverie.

“What is behind the darkness of closed eyes?” This probing thought came powerfully into my mind. An immense flash of light at once manifested to my inward gaze. Divine shapes of saints, sitting in meditation posture in mountain caves, formed like miniature cinema pictures on the large screen of radiance within my forehead.

“Who are you?” I spoke aloud.

“We are the Himalayan yogis.” The celestial response is difficult to describe; my heart was thrilled.

“Ah, I long to go to the Himalayas and become like you!” The vision vanished, but the silvery beams expanded in ever-widening circles to infinity.

“What is this wondrous glow?”

“I am Iswara.10 I am Light.” The voice was as murmuring clouds.

“I want to be one with Thee!”

Out of the slow dwindling of my divine ecstasy, I salvaged a permanent legacy of inspiration to seek God. “He is eternal, ever-new Joy!” This memory persisted long after the day of rapture.

Muslims have visualized Prophet Muhammad in words and calligraphic art for centuries

Hilye, or calligraphic panel containing a physical description of the Prophet Muhammad made in 1718 in the Galata Palace, Istanbul. Dihya Salim al-Fahim, (1718), via Wikimedia Commons

The republication of caricatures depicting the Prophet Muhammad by French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in September 2020 led to protests in several Muslim-majority countries. It also resulted in disturbing acts of violence: In the weeks that followed, two people were stabbed near the former headquarters of the magazine and a teacher was beheaded after he showed the cartoons during a classroom lesson.

Visual depiction of Muhammad is a sensitive issue for a number of reasons: Islam’s early stance against idolatry led to a general disapproval for images of living beings throughout Islamic history. Muslims seldom produced or circulated images of Muhammad or other notable early Muslims. The recent caricatures have offended many Muslims around the world.

This focus on the reactions to the images of Muhammad drowns out an important question: How did Muslims imagine him for centuries in the near total absence of icons and images?

Picturing Muhammad without images

In my courses on early Islam and the life of Muhammad, I teach to the amazement of my students that there are few pre-modern historical figures that we know more about than we do about Muhammad.

The respect and devotion that the first generations of Muslims accorded to him led to an abundance of textual materials that provided rich details about every aspect of his life.

The prophet’s earliest surviving biography, written a century after his death, runs into hundreds of pages in English. His final 10 years are so well-documented that some episodes of his life during this period can be tracked day by day.

Even more detailed are books from the early Islamic period dedicated specifically to the description of Muhammad’s body, character and manners. From a very popular ninth-century book on the subject titled “Shama'il al-Muhammadiyya” or The Sublime Qualities of Muhammad, Muslims learned everything from Muhammad’s height and body hair to his sleep habits, clothing preferences and favorite food.

No single piece of information was seen too mundane or irrelevant when it concerned the prophet. The way he walked and sat is recorded in this book alongside the approximate amount of white hair on his temples in old age.

These meticulous textual descriptions have functioned for Muslims throughout centuries as an alternative for visual representations.

Most Muslims pictured Muhammad as described by his cousin and son-in-law Ali in a famous passage contained in the Shama'il al-Muhammadiyya: a broad-shouldered man of medium height, with black, wavy hair and a rosy complexion, walking with a slight downward lean. The second half of the description focused on his character: a humble man that inspired awe and respect in everyone that met him.

Textual portraits of Muhammad

That said, figurative portrayals of Muhammad were not entirely unheard of in the Islamic world. In fact, manuscripts from the 13th century onward did contain scenes from the prophet’s life, showing him in full figure initially and with a veiled face later on.

The majority of Muslims, however, would not have access to the manuscripts that contained these images of the prophet. For those who wanted to visualize Muhammad, there were nonpictorial, textual alternatives.

There was an artistic tradition that was particularly popular among Turkish- and Persian-speaking Muslims.

Ornamented and gilded edgings on a single page were filled with a masterfully calligraphed text of Muhammad’s description by Ali in the Shama'il. The center of the page featured a famous verse from the Quran: “We only sent you (Muhammad) as a mercy to the worlds.”

These textual portraits, called “hilya” in Arabic, were the closest that one would get to an “image” of Muhammad in most of the Muslim world. Some hilyas were strictly without any figural representation, while others contained a drawing of the Kaaba, the holy shrine in Mecca, or a rose that symbolized the beauty of the prophet.

Framed hilyas graced mosques and private houses well into the 20th century. Smaller specimens were carried in bottles or the pockets of those who believed in the spiritual power of the prophet’s description for good health and against evil. Hilyas kept the memory of Muhammad fresh for those who wanted to imagine him from mere words.

Different interpretations

The Islamic legal basis for banning images, including Muhammad’s, is less than straightforward and there are variations across denominations and legal schools.

It appears, for instance, that Shiite communities have been more accepting of visual representations for devotional purposes than Sunni ones. Pictures of Muhammad, Ali and other family members of the prophet have some circulation in the popular religious culture of Shiite-majority countries, such as Iran. Sunni Islam, on the other hand, has largely shunned religious iconography.

Outside the Islamic world, Muhammad was regularly fictionalized in literature and was depicted in images in medieval and early modern Christendom. But this was often in less than sympathetic forms. Dante’s “Inferno,” most famously, had the prophet and Ali suffering in hell, and the scene inspired many drawings.

These depictions, however, hardly ever received any attention from the Muslim world, as they were produced for and consumed within the Christian world.

Offensive caricatures and colonial past

Providing historical precedents for the visual depictions of Muhammad adds much-needed nuance to a complex and potentially incendiary issue, but it helps explain only part of the picture.

Equally important for understanding the reactions to the images of Muhammad are developments from more recent history. Europe now has a large Muslim minority, and fictionalized depictions of Muhammad, visual or otherwise, do not go unnoticed.

With advances in mass communication and social media, the spread of the images is swift, and so is the mobilization for reactions to them.

Most importantly, many Muslims find the caricatures offensive for its Islamophobic content. Some of the caricatures draw a coarse equation of Islam with violence or debauchery through Muhammad’s image, a pervasive theme in the colonial European scholarship on Muhammad.

Anthropologist Saba Mahmood has argued that such depictions can cause “moral injury” for Muslims, an emotional pain due to the special relation that they have with the prophet. Political scientist Andrew March sees the caricatures as “a political act” that could cause harm to the efforts of creating a “public space where Muslims feel safe, valued, and equal.”

Even without images, Muslims have cultivated a vivid mental picture of Muhammad, not just of his appearance but of his entire persona. The crudeness of some of the caricatures of Muhammad is worth a moment of thought.

https://news.yahoo.com/muslims-visualiz ... 43796.html

Hilye, or calligraphic panel containing a physical description of the Prophet Muhammad made in 1718 in the Galata Palace, Istanbul. Dihya Salim al-Fahim, (1718), via Wikimedia Commons

The republication of caricatures depicting the Prophet Muhammad by French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in September 2020 led to protests in several Muslim-majority countries. It also resulted in disturbing acts of violence: In the weeks that followed, two people were stabbed near the former headquarters of the magazine and a teacher was beheaded after he showed the cartoons during a classroom lesson.

Visual depiction of Muhammad is a sensitive issue for a number of reasons: Islam’s early stance against idolatry led to a general disapproval for images of living beings throughout Islamic history. Muslims seldom produced or circulated images of Muhammad or other notable early Muslims. The recent caricatures have offended many Muslims around the world.

This focus on the reactions to the images of Muhammad drowns out an important question: How did Muslims imagine him for centuries in the near total absence of icons and images?

Picturing Muhammad without images

In my courses on early Islam and the life of Muhammad, I teach to the amazement of my students that there are few pre-modern historical figures that we know more about than we do about Muhammad.

The respect and devotion that the first generations of Muslims accorded to him led to an abundance of textual materials that provided rich details about every aspect of his life.

The prophet’s earliest surviving biography, written a century after his death, runs into hundreds of pages in English. His final 10 years are so well-documented that some episodes of his life during this period can be tracked day by day.

Even more detailed are books from the early Islamic period dedicated specifically to the description of Muhammad’s body, character and manners. From a very popular ninth-century book on the subject titled “Shama'il al-Muhammadiyya” or The Sublime Qualities of Muhammad, Muslims learned everything from Muhammad’s height and body hair to his sleep habits, clothing preferences and favorite food.

No single piece of information was seen too mundane or irrelevant when it concerned the prophet. The way he walked and sat is recorded in this book alongside the approximate amount of white hair on his temples in old age.

These meticulous textual descriptions have functioned for Muslims throughout centuries as an alternative for visual representations.

Most Muslims pictured Muhammad as described by his cousin and son-in-law Ali in a famous passage contained in the Shama'il al-Muhammadiyya: a broad-shouldered man of medium height, with black, wavy hair and a rosy complexion, walking with a slight downward lean. The second half of the description focused on his character: a humble man that inspired awe and respect in everyone that met him.

Textual portraits of Muhammad

That said, figurative portrayals of Muhammad were not entirely unheard of in the Islamic world. In fact, manuscripts from the 13th century onward did contain scenes from the prophet’s life, showing him in full figure initially and with a veiled face later on.

The majority of Muslims, however, would not have access to the manuscripts that contained these images of the prophet. For those who wanted to visualize Muhammad, there were nonpictorial, textual alternatives.

There was an artistic tradition that was particularly popular among Turkish- and Persian-speaking Muslims.

Ornamented and gilded edgings on a single page were filled with a masterfully calligraphed text of Muhammad’s description by Ali in the Shama'il. The center of the page featured a famous verse from the Quran: “We only sent you (Muhammad) as a mercy to the worlds.”

These textual portraits, called “hilya” in Arabic, were the closest that one would get to an “image” of Muhammad in most of the Muslim world. Some hilyas were strictly without any figural representation, while others contained a drawing of the Kaaba, the holy shrine in Mecca, or a rose that symbolized the beauty of the prophet.

Framed hilyas graced mosques and private houses well into the 20th century. Smaller specimens were carried in bottles or the pockets of those who believed in the spiritual power of the prophet’s description for good health and against evil. Hilyas kept the memory of Muhammad fresh for those who wanted to imagine him from mere words.

Different interpretations

The Islamic legal basis for banning images, including Muhammad’s, is less than straightforward and there are variations across denominations and legal schools.

It appears, for instance, that Shiite communities have been more accepting of visual representations for devotional purposes than Sunni ones. Pictures of Muhammad, Ali and other family members of the prophet have some circulation in the popular religious culture of Shiite-majority countries, such as Iran. Sunni Islam, on the other hand, has largely shunned religious iconography.

Outside the Islamic world, Muhammad was regularly fictionalized in literature and was depicted in images in medieval and early modern Christendom. But this was often in less than sympathetic forms. Dante’s “Inferno,” most famously, had the prophet and Ali suffering in hell, and the scene inspired many drawings.

These depictions, however, hardly ever received any attention from the Muslim world, as they were produced for and consumed within the Christian world.

Offensive caricatures and colonial past

Providing historical precedents for the visual depictions of Muhammad adds much-needed nuance to a complex and potentially incendiary issue, but it helps explain only part of the picture.

Equally important for understanding the reactions to the images of Muhammad are developments from more recent history. Europe now has a large Muslim minority, and fictionalized depictions of Muhammad, visual or otherwise, do not go unnoticed.

With advances in mass communication and social media, the spread of the images is swift, and so is the mobilization for reactions to them.

Most importantly, many Muslims find the caricatures offensive for its Islamophobic content. Some of the caricatures draw a coarse equation of Islam with violence or debauchery through Muhammad’s image, a pervasive theme in the colonial European scholarship on Muhammad.

Anthropologist Saba Mahmood has argued that such depictions can cause “moral injury” for Muslims, an emotional pain due to the special relation that they have with the prophet. Political scientist Andrew March sees the caricatures as “a political act” that could cause harm to the efforts of creating a “public space where Muslims feel safe, valued, and equal.”

Even without images, Muslims have cultivated a vivid mental picture of Muhammad, not just of his appearance but of his entire persona. The crudeness of some of the caricatures of Muhammad is worth a moment of thought.

https://news.yahoo.com/muslims-visualiz ... 43796.html

-

mahebubchatur

- Posts: 735

- Joined: Mon Jan 13, 2014 7:01 pm

Ya Ali Madad You have asked “ ..YM : Just To Clarify : Photographs Which You Say Pictures : Are Felt As Symbolic Physical Presence Of The Imam in Jamatkhanas “

My response - Can IIS/Huzur/ITREBS/Ismaili Scholars also share any related material articles Farmans

What are the reasons for photographs-Images of Hazar Imam inside Jamat Khannas.

Images and objects have been there & are used as a part of our Tariqah practices and prayers.

There are also photographs in other areas, for example leading up to the entrance of the Jamat Khanna.

A Question - Why would Hazar Imam ask for images to be moved from the front to the side, and not to be removed totally ?

Was there a report with suggestions prepared and given to Hazar Imam by ITREBS/HUZUR ?

A copy of the report & Farman has not been given to the Jamat (nor was this is taught by Al Waezeens or in Bait ul Ilm - Is it today ?)

Some leaders said at the time that the reason given to them (by the Clique), was that having photographs of Imam in the front gives the impression that we are worshiping the Image of the Imam.

That makes no sense because

1. the images are still there but now on the side.

2. Most look at the images during the congregation. I do too.

3. Why we have images can be explained & clarified very simply

No other faiths for example Christians did not move the image and objects they use, from the front to the sides, inside the Churches?

And, also. who does not know or cannot find out that Ismaili Muslims send our prayers to and through our Imam ? Images or no Images !

During tours of the Jamat Khanna what are the tour guides now told to say about the photographs.

(Can someone tell us if it is not what I am saying)

Images Tasbihs Taweez, and other images & objects are symbolic & are physical symbols of respect which are also used to venerate & or for inspiration and or to focus on prayers generally or of some aspects

In Jamat Khannas symbols include gestures with our hands e.g. shaking hands with a prayer - Shah Jo Deedar or hands on our face during a Salwat in JK

Physical images or physical persons of Imams or other objects/symbols which are there, are not worshiped by Ismaili Muslims .

Physical images including art & objects are in and used in most places of worships today, (e.g. churches temples & most new mosques too)

In our Ismaili Tariquah symbols and objects include the objects used also during our highest religious holy congregation in the presence of and presided by Hazar Imam. This includes the use of symbols/objects including the deedar installation prayers, the Imam’s attire, & related ceremonies. (link below)

Images and objects can also help to focus a person's mind on an aspect of remembrance prayer or worship. (For example, inside the church Jesus on the cross or cross can help to remember the sacrifice of Jesus)

Like us, they are not worshiping the images or objects which are symbolic

In our case our flag or even a Tasbih is traditionally used to focus, and a reminder and of identity and for remembrance and prayer which we do for example with a Tasbih for Tasbihs & calling on the names of Imams Ali Prophet & or Allah.

Physical Images and objects are an expression of respect reverence and veneration. They are symbols. They are NOT being worshipped.

Ismailis worship and send our prayers to & through the Noor (light soul intellect) of our Imam of the time , to the Noor, light Soul Intellect of Allah.

Ismailis do not pray to the physical person/body of the Imam nor to Images or objects which are there inside Jamat Khanna and during Deedars

In Ismaili theology it is the “Light” - the universal intellect & Soul we pray & seek spiritual blessings of enlightenment and to help guide us physically materially and spiritually. ( link)

An idol (object) is a graven image or representation of anything that is revered, or believed to convey spiritual power. Not to be misunderstood with **idolatry** which is the worship of idols

“idolatry, in Judaism and Christianity, is the worship of someone or something other than God as though it were God. The first of the biblical Ten Commandments prohibits idolatry: “You shall have no other gods before me.”

What Hazar Imam said in a Farman regarding the Jamat Khanna in Dubai

“The congregational space incorporated within the Ismaili Centre belongs to the historic category of jamatkhana, an institutional category that also serves a number of sister Sunni and Shia communities, in their respective contexts, in many parts of the world. Here, it will be space reserved for traditions and practices specific to the Shia Ismaili tariqah of Islam.

(Imam Shah Karim al-Husayni Aga Khan IV,)

The Links for those who want to research - read more

https://ask.ismailignosis.com/article/4 ... jamatkhana

http://ismaili.net/timeline/2018/chatur-nyat.pdf

http://ismaili.net/source/chatur-chrono ... rayers.pdf

http://www.ismaili.net/html/modules.php ... pic&t=8668

My response - Can IIS/Huzur/ITREBS/Ismaili Scholars also share any related material articles Farmans

What are the reasons for photographs-Images of Hazar Imam inside Jamat Khannas.

Images and objects have been there & are used as a part of our Tariqah practices and prayers.

There are also photographs in other areas, for example leading up to the entrance of the Jamat Khanna.

A Question - Why would Hazar Imam ask for images to be moved from the front to the side, and not to be removed totally ?

Was there a report with suggestions prepared and given to Hazar Imam by ITREBS/HUZUR ?

A copy of the report & Farman has not been given to the Jamat (nor was this is taught by Al Waezeens or in Bait ul Ilm - Is it today ?)

Some leaders said at the time that the reason given to them (by the Clique), was that having photographs of Imam in the front gives the impression that we are worshiping the Image of the Imam.

That makes no sense because

1. the images are still there but now on the side.

2. Most look at the images during the congregation. I do too.

3. Why we have images can be explained & clarified very simply

No other faiths for example Christians did not move the image and objects they use, from the front to the sides, inside the Churches?

And, also. who does not know or cannot find out that Ismaili Muslims send our prayers to and through our Imam ? Images or no Images !

During tours of the Jamat Khanna what are the tour guides now told to say about the photographs.

(Can someone tell us if it is not what I am saying)

Images Tasbihs Taweez, and other images & objects are symbolic & are physical symbols of respect which are also used to venerate & or for inspiration and or to focus on prayers generally or of some aspects

In Jamat Khannas symbols include gestures with our hands e.g. shaking hands with a prayer - Shah Jo Deedar or hands on our face during a Salwat in JK

Physical images or physical persons of Imams or other objects/symbols which are there, are not worshiped by Ismaili Muslims .

Physical images including art & objects are in and used in most places of worships today, (e.g. churches temples & most new mosques too)

In our Ismaili Tariquah symbols and objects include the objects used also during our highest religious holy congregation in the presence of and presided by Hazar Imam. This includes the use of symbols/objects including the deedar installation prayers, the Imam’s attire, & related ceremonies. (link below)

Images and objects can also help to focus a person's mind on an aspect of remembrance prayer or worship. (For example, inside the church Jesus on the cross or cross can help to remember the sacrifice of Jesus)

Like us, they are not worshiping the images or objects which are symbolic

In our case our flag or even a Tasbih is traditionally used to focus, and a reminder and of identity and for remembrance and prayer which we do for example with a Tasbih for Tasbihs & calling on the names of Imams Ali Prophet & or Allah.

Physical Images and objects are an expression of respect reverence and veneration. They are symbols. They are NOT being worshipped.

Ismailis worship and send our prayers to & through the Noor (light soul intellect) of our Imam of the time , to the Noor, light Soul Intellect of Allah.

Ismailis do not pray to the physical person/body of the Imam nor to Images or objects which are there inside Jamat Khanna and during Deedars

In Ismaili theology it is the “Light” - the universal intellect & Soul we pray & seek spiritual blessings of enlightenment and to help guide us physically materially and spiritually. ( link)

An idol (object) is a graven image or representation of anything that is revered, or believed to convey spiritual power. Not to be misunderstood with **idolatry** which is the worship of idols

“idolatry, in Judaism and Christianity, is the worship of someone or something other than God as though it were God. The first of the biblical Ten Commandments prohibits idolatry: “You shall have no other gods before me.”

What Hazar Imam said in a Farman regarding the Jamat Khanna in Dubai

“The congregational space incorporated within the Ismaili Centre belongs to the historic category of jamatkhana, an institutional category that also serves a number of sister Sunni and Shia communities, in their respective contexts, in many parts of the world. Here, it will be space reserved for traditions and practices specific to the Shia Ismaili tariqah of Islam.

(Imam Shah Karim al-Husayni Aga Khan IV,)

The Links for those who want to research - read more

https://ask.ismailignosis.com/article/4 ... jamatkhana

http://ismaili.net/timeline/2018/chatur-nyat.pdf

http://ismaili.net/source/chatur-chrono ... rayers.pdf

http://www.ismaili.net/html/modules.php ... pic&t=8668